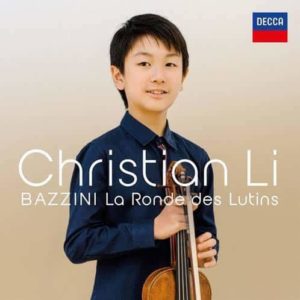

Decca thinks that, with nothing else going on, this is the moment to launch its youngest-ever signing.

Christian Li is a 12 year-old Australian.

The launch track is a Chinese folksong, smooched up for the international market.

Decca thinks that, with nothing else going on, this is the moment to launch its youngest-ever signing.

Christian Li is a 12 year-old Australian.

The launch track is a Chinese folksong, smooched up for the international market.

Never bettered.

Welcome to the 72nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata No. 22 in F major op. 54 (1804)

Before approaching one of the most underrated mature sonatas, let’s take a moment to consider the keyboards that Beethoven had at his disposal. The earliest was a mahogany instrument made by Anton Walter in Vienna, with a range of five octaves. Walter was the most expensive piano builder in the city and Haydn reckoned that only one of his products in ten was any good. Beethoven stuck with him until 1802 when, demanding an ‘una-corda stop’ like most English pianos, he found Walter unable to oblige.

‘Una corda’ is a term that appears in many of Beethoven’s piano scores from this time, sometimes with a German term for added clarity, ‘Mit einer Saite’. What he was after was surgical precision in the left pedal. As the mechanism shifts when the pedal is depressed, he wanted the hammers to pick out one single string, una corda. Simple? It was beyond the wit of Viennese makers.

Beethoven’s next pianoforte was a French Erard of 1803, ‘un piano forme clavecin’, with four pedals, including the essential una corda. It was an unsolicited gift from the Parisian maker, a mark of Beethoven’s growing fame. The instrument, on which the 22nd piano sonata would have been composed, can now be seen in the Kunsthistoriches Museum Vienna. Beethoven would later acquire a six-and-a-half octave Conrad Graf instrument, which now resides at the Beethovenhaus in Bonn.

The transformative moment came in August 1817, when Beethoven received an unprompted visit from Mr John Broadwood of Great Pulteney Street, Golden Square, London. ‘I was introduced to him by his friend Mr Bridi, a banker at Vienna,’ recalled Broadwood. He was then so unwell, his table supported as many vials of medicine and golipots as it did sheets of music paper and his cloaths so scattered about the room in the manner of an invalid that I was not surprised when I called on him by appointment to take him out to dine with us at the Prater to find him declare after he had one foot in the carriage that he found himself too unwell to dine out and he retreated upstairs again. I saw him several times after that at his own house and he was kind enough to play to me, but he was so deaf and unwell that I am sorry to say I had no opportunity of marking anything like an anecdote…’

Broadwood designed for Beethoven a pianoforte with six octaves, two pedals and inlays of marquetry and ormolu. On its arrival in February 1818 Austrian Customs officials were so impressed that they waived all taxes and duties. Beethoven was delighted with the gift, ‘convinced it would inspire something good.’ It did: the late sonatas. On Beethoven’s death it was bought for 181 florins by the music publisher Spina who, in turn, gave it to Franz Liszt. It now holds pride of place at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest. You can hear some of Beethoven’s last Bagatelles played on it here by Andras Schiff. You will hear immediately how far short this instrument fell from the sounds that Beethoven was hearing in his head, how lacking it is in grandeur and dynamic range, how limited in expression. Nonetheless, these are the tools that the composer had to work with and it’s important for us to understand how he handled them.

The 22nd piano sonata, barely ten minutes long, eclipsed by its neighbours, the Waldstein and Apassionata, should not be overlooked. The dates on the manuscript overlap with the first sketches for the Fifth Symphony. As Beethoven’s fingers doodled on his Erard symphonic thoughts were taking shape in his leonine head. The first movement struggles to get going or hold the attention; the second is way too fast and full of itself. As the Canadian pianist Anton Kuerti once put it: ‘If the first movement was constipated, then the second movement suffers from the opposite ailment.’ The sonata is more an exercise than a fully conceived composition.

The Viennese pianist Paul Badura Skoda recorded it twice, initially on a modern piano, then on a period Erard. He was, I think, the first to attempt the entire cycle of 32 sonatas on period instruments and the results are unfailingly revealing if not always easy on the ear. Hammer strikes string with a dullish thud and the artist, no matter how fast he plays cannot conceal the failure of the machine to let ideas flow with the ease their composer intended. Badura-Skoda, who died a few months ago at the age of 91, found old pianofortes in Viennese junkshops in much the same way as Nikolaus Harnoncourt collected instruments for his period ensemble. His contribution to our understanding of Beethoven’s technical difficulties is immense and, as he grows accustomed to the instruments, he achieves real poetry in the very last sonatas. Throughout his enterprise, he maintained a close friendship with Jörg Demus, who was ploughing the same authentic furrows.

The other Beethoven cyclist on fortepiano is the Dutchman Ronald Brautigam, a virtuoso performer who conjures a deeper, more rounded sound from his instruments. Brautigam favours a Walter or a Graf, played in a sonorous church. His five-octave keyboard is a modern copy of the instruments of Beethoven’s time and one suspects it has been tweaked to give a smoother result than the junkshop bargains. Brautigam’s replica was built by Paul McNulty in 2007. Judge for yourself.

Demus, who is unfailingly challenging, does not appear to have recorded this particular sonata. It may be finally coming onto its own. There are thoughtful, historically consistent accounts on modern concert grands played by Jonathan Biss and Igor Levit, both recorded in 2018, leaders of the next exploration.

The international conductor Cristian Măcelaru has signed up for Interlochen’s virtual arts camp, held from June 28 to July 19.

Măcelaru is Chief Conductor of the WDR Sinfonieorchester, Music Director of the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music, and Music Director Designate of the Orchestre National de France.’Cristi has an uncanny ability to energize and inspire our emerging young musicians,’ said Trey Devey, President of Interlochen Center for the Arts. ‘We are grateful for his leadership and thrilled that he will join us for Interlochen Online this summer.’

‘Interlochen set me on the path to create a life in the arts,’ Măcelaru said. ‘It is a privilege to be able to help inspire the next generation of artists to follow their dreams and fulfill their potential, especially during this challenging time.’

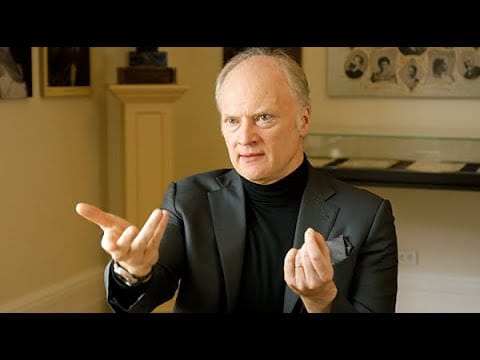

The latest guest on Zsolt Bognar’s In the Classical Life is Gianandrea Noseda, music director in Washington DC and the Zurich Opera.

One of the busiest members of his profession, Noseda like to take time out to reflect on what he does.

‘I think of myself as a narrator, a storyteller,’ he tells Zsolt. ‘The biggest part of my work is at home and alone’.

Very timely.

Watch below.

He has the most discreet and beautiful pocket handkerchief of any conductor presently alive.

Fortune magazine features Rachelle Jonck, a New York vocal coach who works with lots of singers at the Met. Or did.

But since the COVID-19 lockdowns started in mid-March in the United States, one opera house after the other has gone dark, leaving Jonck’s clients idle and unable to make a living: The Metropolitan Opera canceled the last two months of its season, the Lyric Opera in Chicago had to drop its ambitious Wagner Ring Cycle, and the prestigious Santa Fe Opera last week said there would be no 2020 summer season.

Read on here.

However, she’s launched her own vocal boot camp. You can read the full text of the Fortune interview in a PDF on her Facebook page here.

Bert Bial, who played contra-bassoon and bassoon in the New York Philharmonic from 1957 to 1995, has died at the age of 93.

He was also the orchestra’s official photographer on frequent occasions. An exhibition of his work has appeared in Lincoln Center.

A tribute to the singer, who died today, by his pupil Una Barry.

I first got to know Neil from afar in the audience as a young music student and young professional as this wonderful baritone at English National Opera. I must have seen everything he did there – Mozart, Wagner, Debussy, all the first performances [and some last!] in the 70s and 80s. So many there in those days were just outstanding, and of course it was the time of the Reginald Goodall Ring. I saw Neil do Amfortas in Parsifal, and also in a semi-staged performance on 11 August 1987 at the Proms that turned out to be Reggie’s last concert he ever conducted. I remember there was Gwynne Howell as Gurnemanz, Warren Ellsworth as Parsifal, and Sheelagh Squires as Kundry. The Financial Times wrote, “Neil Howlett was a noble Amfortas.” He sure was.

I didn’t know Neil in those days, but in 2012 when I was looking for a new singing teacher with a move out of London to Yorkshire and with Heather Harper and Josephine Veasey both retiring from ill-health, I came across Neil’s comprehensive website of singing articles, knowing that he taught in London and Lincoln and, if we got on, Lincoln via Newark on the mainline would be ideal. Neil’s site was not how to sing by numbers or out of a book but a very practical and scholarly site, given he had done not only all the research but also knew what it was like to get up and do the job. He had also been a fine oboist before he went to King’s College, Cambridge to do English, Archaeology and Anthropology as a choral scholar, and then winning the Kathleen Ferrier Award that then sent him abroad to study with the best and get into German opera houses.

I had a few lessons in London before I moved, and I knew we would more than get on. He was not for the faint-hearted in the profession for he knew the profession was tough, and one thing you needed to succeed was resilience. Over seven years from March 2012 to July 2019, I had 113 lessons. I recorded them all; I typed them up verbatim, and got them bound! May seem odd to some of you, but not only did Neil scrutinise my singing from note to note, he taught me how to teach, which is something I came to very late in life compared to others because of being away so much singing myself as well as my regular work for water and educational projects in Africa. Now having all those lessons to hand, I have a Bible to which I can refer when in doubt for everything is there for my own teaching, as well as what others taught me. I can never say that I ever had a ‘bad teacher’ – they all taught me a lot.

My life as an active public singer is at an end, and never more so now with this Covid situation that has hammered into a profession on my level that may well not be there for the next generation for not all singers can be stars. But if I get back to teaching – if there are any students left to teach – then I will teach whoever as well as I possibly can – even better than I did, in memory of Neil and for all the invaluable knowledge he freely shared. My own students loved him from kids to those in their 70s still wanting and well able to sing, as I made sure they got time with Neil from time to time as he the ‘master teacher’ – a name that used to make him cringe as he was so modest – and me the student teacher. But they all loved him and they learnt so much that was relevant to their stage of development.

So here we are today on what is a very sad day of loss. In saying that, Neil was not afraid of dying. We had the odd conversation about life and death over a cup of tea once in the kitchen as I’d been relearning Verdi’s Requiem with him for two concerts. He certainly did not believe in any life after death or was remotely religious. But it has made me smile today in all this sadness that Neil should have died on Ascension Thursday, one of the big festivals of the Christian calendar throughout the world. Who knows but if there is such a thing as life after death, one thing is for sure: his spirit will live on among us and those of us who knew him well, will not forget him in a hurry. May he rest in peace.

Neil Howlett, principal baritone for 17 years at English National Opera, died this morning in Lincoln Hospital after a lengthy period of illness. He was 85.

Among his 80 roles, he sang the title role in the world premiere of David Blake’s Toussaint (1977) and was the Coliseum’s first-choice Iago and Scarpia. He sang internationally in Italy, France, Germany, Scandinavia, South America and the US.

Neil was a professor at the Guildhall School of Music and, after retiring from singing, Head of Vocal Studies at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester.

The Liverpool conductor Vasily Petrenko is holding open conversations with major players in the classical world on his Facebook page.

In a stark and sober chat, the Concertgebouw chief Simon Reinink disclosed his surprise that two-thrids of ticket buyers have not demanded their money back, either donating the ticket or accepting a voucher.

His prognosis, though, is grim. Reinink acknowledges that the over-70s who form a large part of the classical audience will not return until there is a Covid-19 vaccine or the virus has abated. He also warns of a coming recession that will cause major sponsors to desert.

Watch here:

Ex-Warner record plugger Melissa Lesnie gets out with full Corona kit in her Paris quartier.

Cool, Mel!

Professor Marion Saxer died on Monday in Frankfurt am Main at the age of 59.