Charles Krigbaum, long-serving organist at Yale and head of the Widor Society, has died in at home of Covid-19. He was 91.

He was University Organist at Yale from 1965 to 1990.

Charles Krigbaum, long-serving organist at Yale and head of the Widor Society, has died in at home of Covid-19. He was 91.

He was University Organist at Yale from 1965 to 1990.

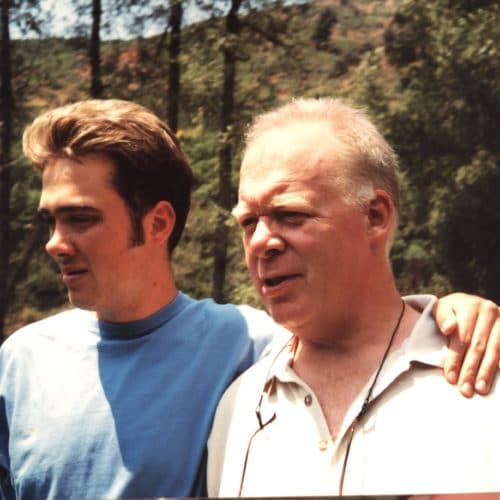

Eben Harrell has shared with us his reminiscences of a marvellous, multi-skilled Dad.

I am sitting on the banks of a high-mountain creek in Southwest Colorado trying to conjure my father, the cellist Lynn Harrell, who died this week at age 76. The water is high from the spring run-off and I do not know if I will find much clarity. But as I approached the banks and heard the water-music build in intensity, I knew I had come to the right spot.

My father loved to fish these alpine streams. He shared that passion with me in the summers when I would follow him to Colorado for the Aspen Music Festival, where he was a mainstay for many years. My father was an incredibly talented man—perhaps the finest cellist of his generation, he was also, at times, a 4.5 USTA-rated tennis player, a single handicap golfer (despite taking up the game as an adult) and a 1800 Elo-rated chess player. Yet he was an enthusiastic but quite ineffectual fly-fisherman. He fished because he enjoyed the poetics of dry-fly fishing—the umbilical connection to nature that a fly-line provided, and the magic of summoning wild trout from the depths simply by dancing shadows across a river’s surface.

We spoke often about the powerful ending to Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, in which the author–an old man alone on the river—uses the rhythm of fly-casting and poetry to try to summon memories of lost loved ones. “Now nearly all those I loved and did not understand when I was young are dead,” Maclean writes, pausing a beat to let the power of his line gather behind him. “But I still reach out to them.”

My father never stopped reaching out. It is what made him such a great musician. In middle age he came to realize how playing the cello was, in part, an attempt to cross a bridge to his own deceased musician parents, particularly his father, a great singer who died when Lynn was still a teenager. He chose the cello as his instrument, he later realized, because of its proximity in range and expression to his father’s voice, and also the posture of its player, which is one of embrace. He obsessively listened to his father’s recordings and spent hours in his practice room honing his technique in the hope of recreating his father’s sound. Among instrumentalists he perhaps came closest to achieving a singing quality in his playing, but in his dark moments he knew his parents remained forever beyond his grasp. Yet he persevered; he was simultaneously comforted, compelled and haunted by the quest. Audiences around the world are richer for it.

This sounds depressing, but I believe it is the opposite. It is life-affirming. Like any great artist, my father understood that art is the only way (perhaps other than religion) to reconcile life’s most tragic elements. It offers moments—just moments—of transcendence. This is why even the most ravaged dementia or amnesia patient can hum their way through a melody without losing their way. T.S. Eliot wrote of “music that is heard so deeply/ that it is not heard at all, but you are the music, while the music lasts.”

There’s a memory I have of my father’s playing when I was a child. It’s one of the first memories. I was ill in bed with a fever. Someone (my mother?) put on my father’s recording of Bach’s cello suites. The Bach suites were written from the inspiration found through one man’s relationship with God. They are meditative, devout, at times exultant in their attempts to summon a celestial harmony. In my feverish state, I remember thinking that my father was actually in the room with me, talking to me, soothing me. When I listened to them in later years as an adult, Bach’s efforts to communicate a strong, out-of-body euphoria, the scales that unfold like a ladder dropped down from heaven, take me back to that night as a child, when I felt my father’s presence in an empty room.

A warm, emotive man with an impish sense of humor and an easy, booming laugh, my father was easy to love. But he was never great at human relationships, and he could hurt people close to him. When I was twenty he divorced my mother and threw himself into a new marriage. When they had two kids, his attention turned to building a new life with them, and he abandoned almost all his previous friends in favor of a new social circle, which I never understood and, if I’m honest, never truly forgave. It was a great paradox at the heart of the man: when he was with you, he was so totally present, but then he could disappear, sometimes forever. I am sometimes haunted by the critic George Steiner’s warning that the student of art “may begin to hear the shouts in the poem louder than the shouts in the street.”

I do not write about this side of my father in bitterness or acrimony. Some of the people once close to my father feel aggrieved. But many feel as I do: grateful for the time with a flawed but incredible artist. My father once told me that when my grandfather Mack Harrell sung Bach’s Cantata, “Ich Habe Genug,” he insisted that program notes not contain the traditional translation—“I am fulfilled” but rather “I ask for no more.”

For many years now, even when we saw one another only once or twice a year, my father’s recordings have been the connective tissue that kept us close. So it will continue to be. His playing is how I want to remember him. Befitting the instrument itself, much of the cello’s greatest repertoire has mourning at its core. I think of the longing melodies of Dvorak’s cello concerto, written with great homesickness after Dvorak moved to America, or the arpeggios—the broken chords–that open the Elgar concerto, perhaps the most profoundly sad opening to any work of art. (“If you want to feel the tragedy of World War I,” my father once told me in one of our long, unforgettable discussions about music, “Listen to the opening bars of the Elgar. An entire society cracked apart, the scalding sadness and cumulative regret of so many lives cut short. It’s all there in just a few opening notes.”)

And so it is.

The challenge for the cellist wishing to master this aspect of the repertoire is to be defiantly mournful—to earn redemption from the heartbreak by showing the audience the beauty inherent in loss. Through the power and physicality of his playing, his near flawless technique, and the singing, human quality of his sound, I believe my father delivered this transcendence in his recordings and performances.

As a child one of my favorite pieces that my father played was Schubert’s An Die Musik, a song also sung by my grandfather. My father read the lyrics at my wedding four years ago.

‘Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden,

Wo mich des Lebens wilder Kreis umstrickt,

Hast du mein Herz zu warmer Lieb entzunden,

Hast mich in eine bessre Welt entrückt!”

“O sublime art, in how many bleak hours,

When the wild tumult of life ensnared me,

Have you kindled my heart to warm love,

Have you carried me away to a better world!”

I have just started the process of grieving and I know there will be much pain and mourning ahead. But as I sit by the playful, gurgling river, I know the memories that scald now will soothe me later. And when I reach out for my father, he will always be there. Music was the best of him. It is the best of us all.

(c) Eben Harrell

Lynn Harrell playing Bach at the border of South and North Korea, April 27, 2019.

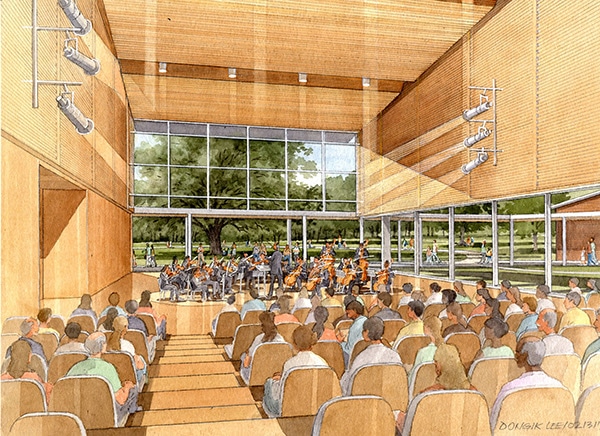

Ravinia, the oldest American music festival running from June to mid-September, has pulled the plug on summer 2020.

The website reminds us that ‘Ravinia has operated continually since its 1904 opening except for 1932–1935, when the park was silenced by the Great Depression.’

This was to have been the final show for Ravinia’s veteran President and CEO Welz Kauffman. He’s working on virtual alternatives for the students who attend its courses: ‘The lives of these young students have been thrown in total disarray, so it is important that Ravinia helps where it can to provide the structure of these virtual classrooms. Our programs give young people a means of expression and connection with each other and their own quarantined families. We teach them that music is their superpower, and what better time than now to have a superpower?’

Tanglewood is now the last major US festival still to declare its future.

UPDATE: I’m reminded that Aspen Music Festival, the biggest in terms of students, has cancelled just the first two weeks. It will decide in mid-May on the rest.

The Boston Symphony has built its 20-21 season around a cycle of Beethoven symphonies with Andris Nelson, a Shostakovich opera, ‘six major works of Richard Strauss’ and a repeat of the Thomas Ades piano concerto.

At a time of mass uncertainty, when the orchestra admits it has no idea of the season will start on time or when, the lack of alternative planning represents a mental lockdown more than a physical one.

Boston has been focussed these past three months on whether or not Tangelwood will go ahead. Probably not, it appears.

That dither time could have been more profitably invested in surprises for the next season, whenever it may start.

Other highlights:

Anna Rakitina, BSO Assistant Conductor in her Symphony Hall debut, leading music of Thomas Adès, Rachmaninoff, and Elgar (11/24-28); Thomas Wilkins, BSO Artistic Advisor for Education and Community Engagement, leading works by Ellington, Gershwin, and Still (1/28-30); Thomas Adès, BSO Artistic Partner, leading music of Prokofiev, Ravel, and Janáček, as well as a reprisal of his highly acclaimed Concerto for Piano and Orchestra Piano with Kirill Gerstein as soloist (2/11-13)

Pianist Mitsuko Uchida joining the BSO and Andris Nelsons for performances of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 3 (4/22-27)—the start of a three-year cycle of performances of the five concertos; additional acclaimed soloists include Emanuel Ax, Yefim Bronfman, Rudolf Buchbinder, Daniil Trifonov, Inon Barnatan, and Paul Lewis; violinists Augustin Hadelich and Gil Shaham; cellist Yo-Yo Ma; vocalists Kristine Opolais, Brandon Jovanovich, Lise Davidsen, Sir Willard White and Renée Fleming

Guest conductors Giancarlo Guerrero (Julia Wolfe, Her Story, written in commemoration of the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment and Gorecki Symphony No. 3, Symphony of Sorrowful Song, 11/5-7); Dima Slobodeniouk (Stravinsky’s complete Firebird and music of Mendelssohn, 11/12-17); Alan Gilbert (Nielsen Symphony No. 3, music of Bartók and Beethoven, 11/19-21); Herbert Blomstedt (Sibelius Symphony No. 4 and Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, 3/4-6)

Welcome to the 64th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Songs opp 48, 52, 75 and 83

We don’t know why Beethoven chose to write in any of the forms he did, why one idea would give rise to a piano sonata, another to a string quartet and a third to a full symphony. What we do know is that writing songs was hardly ever his first impulse. In surviving sketches, we see him jotting down notes but never words – unlike Schubert, for instance, who would often do both. At the far end of the 19th century, Gustav Mahler would sketch out songs that served him as the nucleus of a symphony. Beethoven wrote a symphony without thinking of a song.

Perhaps he knew he was not a great song writer. In the same way that he did not compete with Mozart in writing comic opera, he was not concerned with participating in the growing taste for Lieder, which both Mozart and Haydn were prepared to feed. When Schubert wrote songs he took his cue from the two dead masters, rather than from the living Beethoven.

That said, Beethoven did write songs – two sets of Lieder, opp 48 and 52, two of Gesänge, opp 75 and 83, and a further set of Arietten, opus 82. He also composed, ahead of Schubert, the first authentic, free-standing cycle of Lieder, An die ferne Geliebte, which I’ll consider later. The songs he wrote are relatively unknown. If ever you whistle a tune of Beethoven’s, it’s unlikely to be from a symphony.

The oldest recording of a Beethoven song dates from 1911. It is sung by the American baritone Arthur van Eweyk with pianist Charles Albert Baker. Eweyk has a formidable instrument and something of a fairground manner, but you won’t be sorry you’ve heard him. You really won’t.

In his first published set, Beethoven chose six songs by the theologian Christian Fürchtegott Gellert (1750-1769), a poet whose entire works had previously been set to music by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Beethoven learned these texts from his childhood teacher in Bonn, Christian Neefe. What appealed to him was not so much their doctrinal faith as their celebration of the presence of God in nature. He would also have been aware that their author Gellert was a prominent Protestant whereas his own background was Catholic.

The signature song ‘Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur’ (God’s glory in Nature) receives a magnificent 1936 rendition from the great Norwegian soprano Kirsten Flagstad, an interpretation that is almost churchlike in its devoutness, accompanied at the piano by her worshipful American biographer Edwin Macarthur. Flagstad is indispensable.

The supreme German Lieder singer Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau gave his first account of the set in 1955 with the pianist Hertha Klust. It is comparatively austere – colourless, even – when set beside the partnership he was about to enter with the English pianist, Gerald Moore, whose encouragement elicited far more dramatic performances.

Fischer-Dieskau dominates both opus 48 and 52. Never pushing the voice at top or bottom, he develops effects that make the songs more interesting than they really are. Sometimes, by being too mannered, he achieves the exact opposite, but in his 1966 set with Jorg Demus, he is almost playful. Among other versions, Jessye Norman (with James Levine at the piano) is a bit empty-churchy. Matthias Goerne, with Jan Lisiecki in 2019, has a tiptoeing reverence, a pastel colouring that will grow on you.

In one of the eight songs in opus 52, Mailied, Fischer-Dieskau is put to the sword by the greatest German lyric tenor, Fritz Wunderlich. In Mailied Wunderlich illustrates the futility of effort. Everything he does flows naturally, bringing the most out of this song by sheer lack of effort. You may not want to hear any other man sing it after this. A 2008 Wigmore Hall recital by Ann Murray and Roderick Williams, with Ian Burnside at the piano, gently brings out the set’s domestic dimensions. The young Peter Schreier, recording in Dresden’s Lukaskirche in 1968-70, treats the set like second-quality Schubert. Taken more slowly than most, he finds fresh depths; the pianist is Walter Olbertz.

The six songs opus 75 contain a genuine signature song ‘Kennst du das Land’ (also known as Mignon), and a grappling with Goethe’s Faust. The set does not hang together thematically. The US soprano Rachel Willis-Sørensen taps a deep vein of homesickness in Kennst du. The Finnish soprano Karita Mattila is more florid in Neue Liebe. Nikolai Gedda is irresistible in the Faust number. There’s a recording of the complete set here.

The Ariettas, opus 82, are Italian porcelain designed in Vienna. A listen to Cecilia Bartoli with Sir Andras Schiff at the piano will give you all you need to know. For curiosity value you might also try the counter-tenor David DQ Lee with Yannick Nezet-Séguin at the piano.

*

Adelaide, opus 45

This is one of Beethoven’s earliest songs, written and revised several times in his 20s. The theme is roughly ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ but he never fully works out where he’s going. None of which stops the greatest singers from trying to work it out.

Heinrich Schlusnus, the first on record in 1930, makes it sound almost like a musichall torch-song. Jussi Björling (1939) takes it much more slowly, a drawing-room lovesong to a distantly glimpsed loved one, with a floated top note that is out of this world. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

sounds prosaic by comparison, as does everyone else until Fritz Wunderlich who sings it quite quicklyas a take-it-or-leave-it ultimatum to the wandering lover. Wunderlich invests everything he touches with a tantalising hint of fickleness. Among modern singers, Matthias Goerne (2019) owns it.

If Schubert had written this song, he would have broken someone’s heart. Beethoven is a neutral observer, non-committal, almost empirical in his attitude.