Doriot Anthony Dwyer, principal flute of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1952 to 1990, died yesterday in Kansas at the age of 98.

She was only the second woman to win a principal chair in a major US orchestra, beind Helen Kotas, who became principal horn of the Chicago Symphony in 1941.

Doriot was a legend among US orchestral musicians, leaving a lasting imprint on the Boston sound. Her application for the position was supported by no less than Bruno Walter, who heard her play in the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. Boston had no changing room for women. Her first appearance was greeted with the headline: Woman Crashes Boston Symphony: Eyebrows Lifted as Miss Anthony sat at Famous Flutist’s Desk. Approached by a reporter in 1952, she said: ‘Gradually, during my life, I’ve got used to the idea that I’m a woman.’

mong many recordings, she gave a fine performance of Bernstein’s Halil. On her retirement, the orchestra commissioned a flute concerto for her to play by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich.

San Franciso Symphony has taken the lead, cancelling the whole of April and beyond.

Due to an extension of the Public Health Order prohibiting gatherings of 100 or more persons to slow the spread of COVID-19, there will be no concerts or events at Davies Symphony Hall through April 30.

Houston Grand Opera has called off its two spring productions and it fundraising opera ball. But it has pledged to take care of freelancers:

HGO is taking the lead in helping defray the impact that this cancellation has on our community of artists, musicians, stagehands, and staff. From ushers to star sopranos, HGO is committed to the livelihood of all those involved in producing great opera in Houston. We are asking for you to donate the cost of your tickets from the spring rep to help us offset the losses of those involved.

Gilmore International Keyboard Festival has cancelled halway into May.

South Dakota Cello Day on April 30 is off.

Bizarrely, the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels sent out a note to competitors this weekend saying nothing has been changed and they are expecting to go ahead in May. So they should just go ahead and book flights?

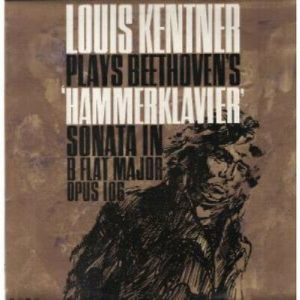

Welcome to the 45th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Hammerklavier sonata, opus 106 (1819)

The 29th sonata, in B-flat major, was recognised as the summit of piano music, a status it maintained for a whole generation until Chopin and Liszt presented a different set of challenges. Even then, it maintained a kind of holy-mountain isolation as pianists feared to tackle its dangerous slopes. For years, it stood unplayed. The first to perform it in public was Franz Liszt, at the Salle Erard in Paris in 1836, to general incomprehension. Pianists ever since have asked themselves: can I play it? should I? dare I? Beethoven’s British publishers had such little faith in being able to sell it that they published only three movements.

Beethoven gave a metronome marking of 138 to the opening allegro movement, a deterrent speed that most considered impossible. It is followed by a two-minute scherzo – blink and it’s over – and two slow movements, a 20-minute adagio and a mystifying largo. The work can last between 40 and fifty minutes. Almost every page carries the warning ‘do not try this at home’. From the amount of ink that has been spilled on the sonata over two centuries, you’d think that a PhD in philosophy was required just to listen to it.

Towards the end it seems that the composer has either run out of ideas or left us suspended in in mid-air until, without prior notice, he plunges at breakneck speed into an allegro risoluto that resolves absolutely nothing. No-one leaves this sonata unshaken. Beethoven wrote: ‘Here’s a sonata that will challenge pianists and that people will be able to play in 50 years.’ The title alone has no particular significance. It is the German word for ‘pianoforte’ and Beethoven had applied it once before, to his sonata opus 101. By the time he wrote the Hammerklavier, Beethoven was completely deaf. We can only speculate what sounds he imagined might emerge. One of my critical colleagues describes it as ‘music to play when you have just broken up with a best friend’.

There are more than 100 recordings of the Hammerklavier, starting in 1935 with Artur Schnabel, who is well beow form in what was, in concert, one of his trademark pieces. Maybe it just rained that day in Abbey Road. The earliest recording to catch my ear is by Louis Kentner (1905-1987), a Hungarian prodigy who settled in England in 1935 and eventually became Yehudi Menuhin’s brother-in-law and recital partner. There is nothing flashy about Kentner, as there would have been about his compatriot Liszt. Kentner attacks the opening difficulties at the prescribed speed and with dignified assurance, a decorum that turns majestic as he enters the great adagio. Kentner, who taught at Menuhin’s school, was either a very modest man, or one of limited ambition. He deserves a higher reputation.

The opening statement in 1956 by the English pianist Solomon is among the most arresting ever heard and the performance as a whole is an act of storytelling, the pianist holding us spellbound start to finish. What sticks in the mind is the clarity of his touch, allied to its lightness, even in the loudest passages. I am not sure there is, anywhere, a more likeable interpretation. Tragically, this is almost the last we hear of Solomon, who suffered a stroke later that year and never played again, though he lived until 1988.

The Austrian-born, London-based Alfred Brendel made the Hammerklavier his calling card through much of a long career. He starts out at a brisk 41 minutes in 1964, slowing to 43 minutes by 1996, adding a gloss of gravitas and sweet touches of wit. What the record industry loved about Brendel was his efficiency in studio, his appeal to both the high-minded and the mass-market, and his ceaseless industriousness in the classical and romantic piano repertoire, seldom allowing weeks to go by without making a record (although Maurizio Pollini (1977) collected more five-star reviews). To my mind, the third all-purpose label pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy is strongest in the Hammerklavier.

Their antipode is the American intellectual and bon-vivant Charles Rosen, who stepped very rarely into the record studio and once boasted to me of the smallest audience he ever attracted – 15 people, most of them Nobel prize winners. Rosen (1971), for all his cerebral snobbery, is touchingly tender in the adagio and subtly edifying in the finale. Beside him, and in the same year, same label, the gravely reserved Rudolf Serkin seems practically a populist.

The Russians have their own way with this sonata, or rather several ways. Sviatoslav Richter (1976) is unmissable for the surprises he springs in the most familiar phrases of the work, as if he is rethinking it as he plays. Some ascribe a similar individuality to Grigory Sokolov (2016) apparently the only pianist to run over 50 minutes, but who’s counting? At the opposite extreme, the mystic Maria Yudina clatters away for 38 minutes on a badly maintained piano in appalling studio sound and an absolutely transfixing reading. It has taken decades for this tape to be exhumed and you really need to hear it. More recently Igor Levit (2013) is unignorable for sheer flair, courage and chutzpah. His is a very 21st century, ultra-communicative Hammerklavier.

Which leads me to the most penetrative of the Russians, Emil Gilels, who was supposed to deliver a full cycle of sonatas for Deutsche Grammophon but, in the late Cold War era, fell two or three short. Gilels, who wore a perpetual haunted look, was shadowed by KGB men wherever he went. He died in 1985, still in his sixties. In one of the slowest performances of the Hammerklavier, he takes us on an inner journey where he can be entirely himself. I think this recording, made in 1983, might be his most important legacy – indeed, possibly the most powerful interpretation of any Beethoven sonata

He is the alltime first choice of our panellist Erica Worth, editor of Piano magazine. Erica is also keen on Mitsuko Uchida (2007) whom she finds ‘far removed from selfish virtuosity and with a strong musical conviction’, valid qualities, as well as a distinctly feminine form of instrospection. Other panel favourites? The Israeli critic and psychoanalyst Amir Mandel directs me to Murray Perahia’s second recording, made in 2018 for DG and the fruit of a lifetime’s all-weather engagement with this force of nature. After years of struggle with a hand injury, Perahia conveys a sense of resignation, with a touch so delicate it is almost weightless

For those in need of retuning, there’s an orchestration of the Hammerklavier by Felix Weingartner, conducted by the composer in 1930 and not nearly as awful as it ought to be. That attribute falls to the arrangement for piano and electronics and another for string quartet – seriously, no.