Welcome to the 41st work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Leonore overtures 1,2 and 3, opus 138, 72a and 72b

A composer of Beethoven’s unshakeable self-assurance does not let anyone see what goes on behind the making of a new work. He may leave messy sketches for abandoned pieces and a few doodles for works in progress, but Beethoven does not on the whole reveal to outside eyes the struggles that he endures in the act of creation, let alone his occasional ambivalence about the material he is moulding.

The great exception is his opera Fidelio, a work that he revised twice after its 1805 premiere and which he furnished with four different overtures, each of which reveals hesitations, second thoughts, uncertainties and insecurities that are quite untypical to this most confident of composers. Two of these overtures are in general use, the other two esoteric. Sorting out which is what is not the easiest of tasks. At the risk of over-simplification, I shall try to keep the process as clear as I can. Bear in mind, though, that this was the overture that awoke Richard Wagner, aged 13, to the possibilities of opera. ‘The direct result of this (1826) performance,’ he wrote, ‘was my intense longing to compose something that would give me a similar feeling of satisfaction.’

Beethoven was persuaded to write an opera in 1803 by Emanuel Schikaneder, librettist of Mozart’s Magic Flute and co-owner of the Theater an der Wien. Schikaneder, looking for a second hit with his name on it, tempted Beethoven with promises of a respectable fee and a free apartment in the theatre complex. Beethoven, often nervous at the approach of rent day, accepted with delight and started work.

Schikaneder’s libretto turned out to be unsuitable. Titled Vesta’s Fire, its central character was a Roman woman with several lovers who became a vestal virgin (don’t ask). Beethoven, after sketching three or four scenes, gave up. ‘I have finally broken with Schikaneder,’ he told a colleague. ‘He held me back for six months, and I let myself be deceived because… I hoped he would produce something cleverer than the usual. How wrong I was… Imagine a Roman subject (of which I had been told nothing) with language and verses such as could come out of the mouths of women apple-sellers in the Vienna markets…’

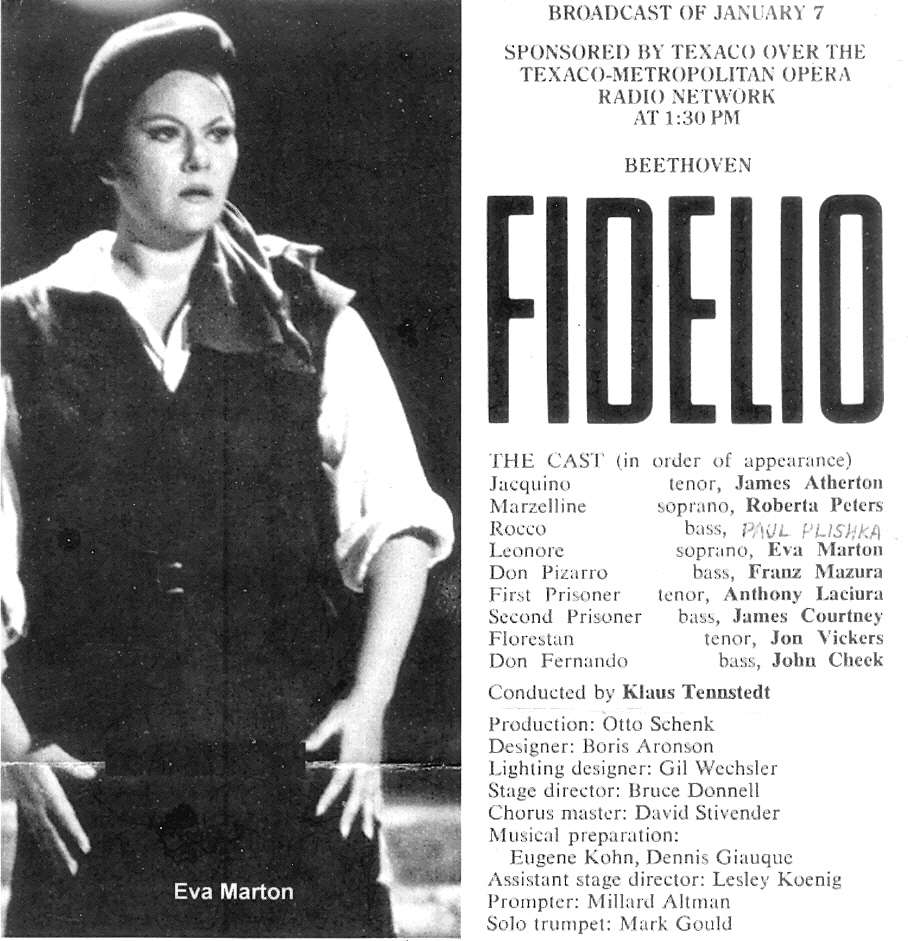

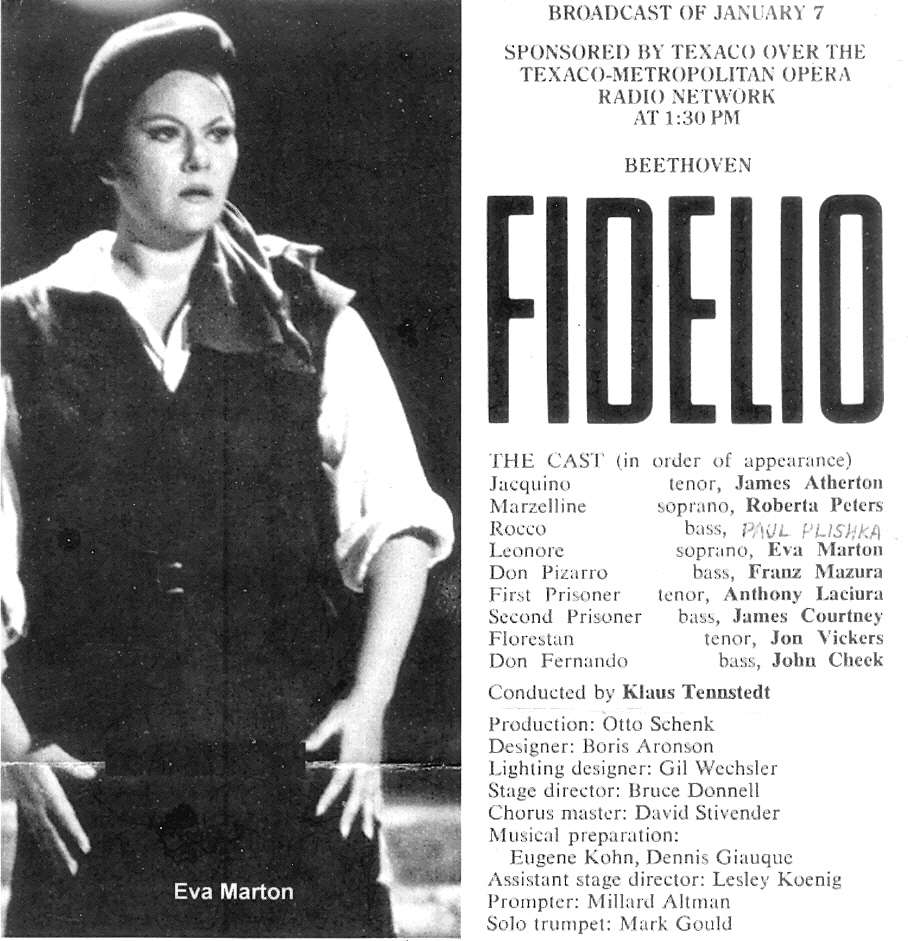

Staying on rent-free at the theatre, Beethoven began an opera under the title Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe (the triumph of married love), adapted from a French play by Joseph Sonnleithner. Never one to waste good music, he used a page from Vesta in the climactic “O namenlose Freude” duet. The 3-act opera was staged in November 1805 under the name ‘Fidelio’ to avoid confusion with several other plays and operas called ‘Leonore’. The score that Beethoven published, however, was titled ‘Leonore’.

Vienna was under French occupation and the premiere, before a mostly military audience, went down badly. Its overture is now numbered Leonore 2.

Before the opera was restaged in April 1806, Beethoven shortened it to two acts and stuck on a fresh overture, Leonore 3. At the next revision in 1814 the opera was callled Fidelio and furnished with a fourth overture, known today as the Fidelio overture. The original Leonore no 1 overtured was tacked on posthumously to Beethoven’s catalogue as its final entry, opus 138. Still with me?

The four overtures have audible differences – an extra drum roll, a contemplative flush of strings – some experimental, others insubstantial. The main thing to remember is that Leonore 1 is much shorter than the others. It comes in at 9-10 minutes, while Leonore 2 and 3 run to 14 minutes or more. In George Szell’s exhilarating 1968 interpretation it sounds like an invitation to all sorts of possibilities, many of them nothing to do with the prison drama that Beethoven is about to enact. Szell delivers Leonore 2 on the same recording for ease of reference, although only people writing a doctoral thesis will want to attempt repeated comparison. There are plenty more recordings of Leonore 1 and 2, the instantly recommendable ones including the no-nonsense John Eliot Gardiner, the authoritative Fritz Busch (1950), the unassumingly satisfying Wolfgang Sawallisch , the enegretic Günter Wand (1991), the imposing Bernard Haitink with the London Symphony Orchestra (2005), and the unaccountably underrated Stanisław Skrowaczewski with the Minnesota Orchestra in 1994.

But the best known and most performed Leonore overture is number 3 and that acquired an independent existence around the turn of the 20th century when Gustav Mahler, director of the Vienna Opera, inserted it into Fidelio as an orchestral interlude in the middle of the second act, after the prison scene and ahead of the finale, in order to heighten the drama. He went on to liberate the overture altogether from the opera, performing it as a concert item no fewer than 18 times. Mahler made extensive changes, known as ‘retouches’ to Beethoven’s instrumentation, principally by cutting back the strings and giving greater prominence to the brass. Leonore 3 thus became the best known of the four overtures.

Bruno Walter, Mahler’s closest disciple, gives the clearest indication as to how Mahler’s version might have sounded with a 1936 Vienna Philharmonic recording which has Mahler’s brother-in-law Arnold Rosé in his customary front seat, directing the strings. The approach alternates leisurely charm with unprovoked aggression, a peculiarly Viennese combination that I find profoundly unsettling, especially in the closing pages, from 11 minutes onwards.

A couple of years later, in Dresden, Karl Böhm presents an expensive velvet glove with a mailed fist that bursts through at 12.30. Böhm was a brilliant theatrical musician and a sworn Nazi; he must have known what he was delivering to the microphones. Wilhelm Furtwängler in Vienna, June 1944, is almost his antipode, introspective where Böhm exaggerates and suggestive where he is over-explicit. This is another of those inexplicable Furtwängler performances that imprints a date/time stamp on the music as it is heard.

Ferenc Fricsay, a Hungarian who conducted Berlin’s radio orchestra in the 1950s, gives an uplifting 1958 account of the overture with the Berlin Philharmonic and another, two minutes slower and three years later with his own ensemble. The second is an exercise in taking all of the beauties out of the score, holding them up to the light, examining them from all angles and replacing them in perfect order. Taken together, these two performances amount to a masterclass in the maestro art, an analysis of all the possibilities in an important score. Against all my expectations, Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra reflect something of Fricsay’s inquisitive approach in their late account of this score in 1989, albeit faster and much louder.

You want slow? There’s Sergiu Celibidache at 16.22, to no obvious purpose. You want exciting? Bernstein and the NY Phil. You want small-scale? Daniel Harding and Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen do tender and beautiful. Dramatic and compact? Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe take some beating. The range of dynamics and the internal tempi are just right.

That’s enough of overtures. Tomorrow, we’ll assess the whole opera.

UPDATE: Did someone say Klemperer? Watch this space.