Gabriela Montero had an hour to spare at at Connolly Station in Dublin, so she sat down and played Mozart.

Did anyone pay attention?

Here’s what she writes:

I had never DARED to play on a public piano because I was too embarrassed to do so!

Until today…

But, since I was only able to practice a third of my repertoire this morning at 8 am before I flew to Ireland, I decided to go for it and practice at Connolly Train Station in Dublin. I had an hour to spare.

My hands were freezing, I felt ridiculous (totally exposed!) but I got through some of the Mozart Sonata, Kinderszenen, and a sweet old Irish lady shyly approached me to thank me.

Welcome to the 36th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven 5th symphony (continued from yesterday)

Those four opening notes are the most peremptory introduction to any work of music. No composer grabs an audience so rudely by the ears until Gustav Mahler in his fifth and sixth symphonies a century later. Beethoven is announcing that he is done with good manners. The fifth is the demarcation line between a conventional composer and a dangerous one. From now on, it’s all or nothing. Hector Berlioz wrote that the fifth symphony is ‘the first in which Beethoven gave wings to his vast imagination without being guided by or relying on any external source of inspiration.’

What message Beethoven meant to convey has been subject to much speculation; whatever it was, it was big. Eighteen months after its first performance, the author E. T. Hoffmann wrote a long review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, arguing that the symphony captures our greatest joys and fears. Hoffmann established Beethoven as the cornerstone of romanticism: ‘Beethoven’s music wields the lever of fear, awe, horror, and pain and it awakens that eternal longing that is the essence of the romantic… What instrumental work by Beethoven confirms this to a higher degree than the profound Symphony [No. 5] in C Minor, a work that is splendid beyond measure. How irresistibly does this wonderful composition transport the listener through ever growing climaxes into the spiritual realm of the infinite.’

Hoffmann, in this 1813 essay, fixes and distorts Beethoven’s image for all time to come without taking us any closer to any inner truth. The work was titled Fate Symphony by the publisher, because Beethoven had muttered something about fate knocking at the door, but we have no idea who Beethoven was expecting and why he makes us so alarmed.

All we can rely upon is a tradition of posthumous performance that begins with Felix Mendelssohn’s influential leadership in Leipzig, followed by Richard Wagner’s powerful advocacy in mid-century. Two Hungarians who played under Wagner’s baton at Bayreuth, Arthur Nikisch and Hans Richter, embedded Beethoven style at the heart of the repertoire – Nikisch in Leipzig, Boston, London and Berlin, and Richter in Vienna, London and Manchester. No record survives of Richter. Nikisch, in November 1913, chose Beethoven’s fifth as the symphony loudest enough to overcome the ambient noise of primitive recording. Forty members of the Berlin Philharmonic strings and brass were clustered aound a big horn and someone threw a switch.

What can we learn from this intriguing and essential recording? Nikisch was quick in the outer movements, more relaxed in the middle. Although he pronounced the result ‘overpowering’, he had no control over the wretched sound differentiation and did the best he could in the circumstances. Seven years later Arturo Toscanini’s recording of the finale at La Scala is much clearer, though still far from a true picture of orchestral dynamics and intepretative tradition. Over time, Toscanini developed a crisp Beethoven style of his own, exemplified in his New York recordings, hard-driven and still in poor acoustics. Some, nonetheless, swear by Toscanini’s self-proclaimed authenticity.#

The most daring Beethoven conductor in his time was Gustav Mahler, changing the instrumentation in the ninth symphony and making an orchestral version of one of the string quartets. Mahler’s close disciples, Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer, exemplify opposite aspects of his character – Walter conventional and emollient, Klemperer brusque and improvisatory. There’s a wild Klemperer performance at the Hollywood Bowl in January 1934, possibly taken during one the manic phases of his bipolar condition and in ropey conditions. You’d be better advised to listen to his glorious mono account of 1955 with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London. Justly considered one of the great recordings of the century, Klemperer makes individualistic changes to the score, getting the violins to play pizziccato at the end of the second movement and making an unscripted repeat of the exposition in the finale. The alterations bolster the work’s archtiecture, making it feel more secure and less revolutionary.

I expected Bruno Walter to take a safer course, and I was wrong. Conducting the New York Philharmonic (in excellent form) in the CBS 30th Street studio in 1950, he takes a fairly tepid approach to the asssertive opening, allowing the tension to accrue organically through the work to a nerve-tingling conclusion that will take your breath away. Never a knee-jerk admirer of Walter’s, I am utterly won over by this reading.

Also not to be missed is a performance conducted by Richard Strauss with the Staatskapelle Berlin in 1928. It’s super-fast and ultra-flexible, with nifty little composer touches as Strauss holds back the strings at times til their fingers ache. The oboe solos are almost operatic in their soft, singing style. Willem Mengelberg‘s 1940 recording in Amsterdam, on the other hand, is simply eccentric and in all the wrong ways, pulling the tempi around and flicking them back like elastic bands. It’s not without excitement.

Wilhelm Furtwängler, the most robbery of maestros, is best heard live in Beethoven’s Fifth, rather than in studio. I have narrowed down to choice to between June 1943 Berlin – a breezily triumphalist performance – and 1954 Vienna, more sedate, at times defeatist. Extraordinary that such contrast can be drawn from the same notes.

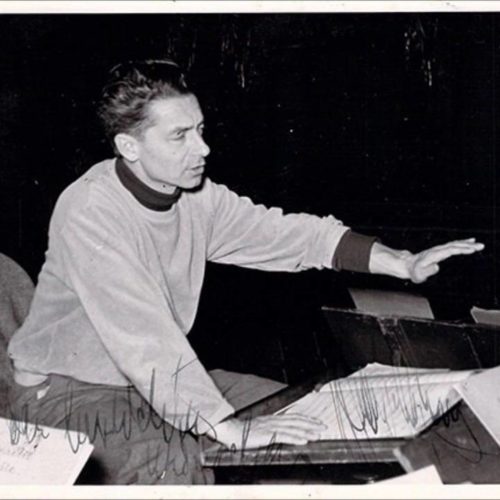

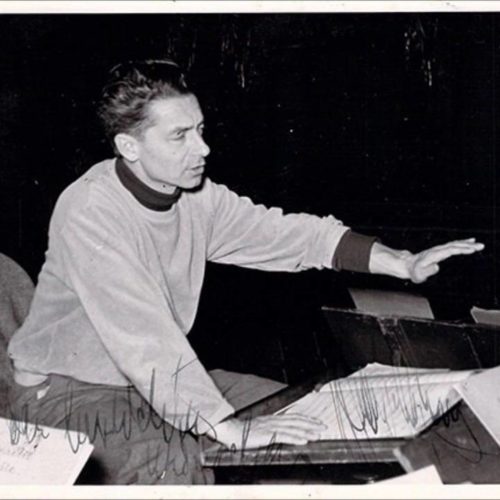

Which brings us to Furtwängler’s Berlin successor, the prolific Herbert von Karajan. There’s a 1948 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic but the full Karajan treatment is heard to best effect in his 1954 recording in London with the Philharmonia Orchestra, many of whose ex-army players regarded him (they told me) as an unregenerate Nazi and their natural enemy. The tension that is palpable throughout this performance owes much to that irreconcilable animosity but the music transcends human conflict and its momentum is irresistible.

Karajan would record this symphony again and again in Berlin and Vienna, each time with refinements that ironed out its jagged edges, but never again did he obtain the near-perfect internal balance and natural propulsion of this Abbey Road session. Several members of my panel, led by the former EMI chief Peter Alward, regard it as paramount. Our American experts swear by the unflappable Georg Szell.

Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at more recent recordings, especially those on period instruments.