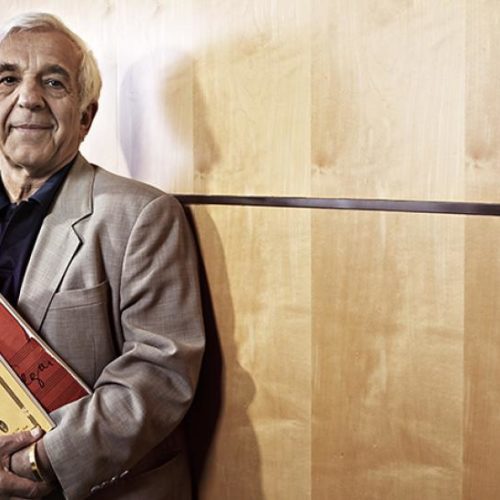

The conductor Hans Swarowsky enjoyed the confidence of the music-loving Nazi governor of Poland, Hans Frank, a man responsible for millions of murders.

After the War, Swarowski became the go-to conducting teacher in Vienna, with Abbado and Mehta among his pupils.

Now reports are emerging that he saved lives in Krakow by hiding Jews in his chorus and orchestra, regardless of whether they could sing or play. Report here.

Welcome to the 15th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Triple concerto, opus 56 (1803-4)

The piano trio – violin, cello, keyboard – was the first work of Beethoven’s to find a publisher and he kept looking for ways to develop the form. His most ambitious effort, at the turn of the 19th century, was to write a concerto for piano trio and full orchestra. The work is a failure, a noble and ultimately absurd attempt by a superchef to see if ice-cream goes with mustard and cheese.

Any amateur can see why it won’t work. A concerto is a balance between conductor, orchestra and soloist whose role is to be first among equals. When there are three soloists, none is primus. The maestro, orchestra and the trio are never quite sure who’s in charge. For the listener, it’s no less confusing. Beethoven spins our heads from one centre of gravity to another. It can be quite wearing.

Sometimes, however, the triple pays out. A 1949 recording by Bruno Walter, always so assured in Beethoven, and principals of the New York Philharmonic – John Corigliano and Leonard Rose with the pianist Walter Hendl – has about it a freshness and an infectious naivety that is hard to resist.

Leonard Bernstein, leading the same orchestra from the piano in 1959 with Corigliano and Laszlo Varga, is considerably less convincing.

Ferenc Fricsay, a Hungarian refugee in charge of the Berlin radio orchestra in the year the Wall went up, finds an ominous note in the opening and sustains a tension that I have never experienced in any other performance. His 1961 soloists are Géza Anda (Piano), Wolfgang Schneiderhan (Violin), Pierre Fournier (Violoncello). Do not overlook this dazzling and timely interpretation.

The most expensive recording of the triple concerto was made by EMI in Berlin eight years later with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic and three premier Soviet exports: David Oistrakh (violin), Sviatoslav Richter (piano) and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. There are two ways of describing how awful it is. One is to read Richter’s recollection: ‘It’s a dreadful recording and I disown it utterly… Battle lines were drawn up with Karajan and Rostropovich on the one side and Oistrakh and me on the other… Suddenly Karajan decided that everything was fine and that the recording was finished. I demanded an extra take. ‘No, no,’ he replied, ‘we haven’t got time, we’ve still got to do the photographs.

The other is to compare is to compare it to the Soviet Melodiya recording where the same soloists, who were never friends, gave a 1972 concert in Moscow, conducted by Kirill Kondrashin and conveying, despite poor sound quality, a unity of purpose that they never approached in Berlin.

Other options in the triple concerto are topped by the Beaux Arts Trio – so used to playing together they are equivalent to a single soloist – with the London Philharmonic and Bernard Haitink in 1977. Bernard Greenhouse on cello is especially evocative.

A 1994 Leipzig retake by a different Beaux Arts formation and Kurt Masur is less cohesive.

George Szell’s Cleveland recording with Isaac Stern (Violin), Leonard Rose (Violoncello), Eugene Istomin (Piano) has plenty of fury but not clean enough sound.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s 2004 modern instrument account with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Thomas Zehetmair (Violin), Clemens Hagen (Violoncello), Pierre-Laurent Aimard (Piano) is particularly captivating in the short Largo central movement.

And then there’s Martha Argerich in at least three recordings, of which I prefer the most recent, 2019, with Ion Marin, Hamburger Symphoniker, Martha Argerich (Piano), Mischa Maisky (Violoncello), Tedi Papavrami (Violin) – where everyone seems to dance attendance on the pianist who is in a world of her own. Just inspired.