The parents of the much-loved baritone will instal a sculpture by Vladimir Usov on his Moscow grave on October 16, his birthday, when their son whould have turned 57.

He died in London of cancer on November 22, 2017.

The parents of the much-loved baritone will instal a sculpture by Vladimir Usov on his Moscow grave on October 16, his birthday, when their son whould have turned 57.

He died in London of cancer on November 22, 2017.

Francois Girard’s movie of my novel, with Tim Roth and Clive Owen, goes on US release on December 25.

Here’s the official cinema trailer, out today:

Collider’s commentator says: ‘The film, based on a novel from music commentator turned novelist Norman Lebrecht, looks to be equal parts Oscar-friendly prestige picture and procedural nailbiter — a work as interested in character sensitivity as it is in nail-biting depictions of obsession.’

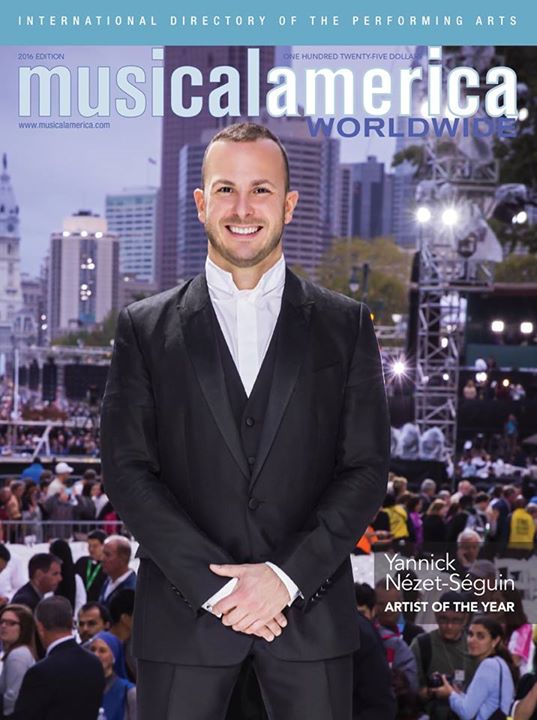

You may recall that we posted a video from a Youtube channel called ‘This is Opera’ which contained some unflattering comments and demonstrations of the expertise of the Met’s music director in vocal technique. The post attracted 143 heated comments.

After a couple of days, both the original clips and the video’s comments (though not SD’s) were deleted, presumably under some form of pressure.

Nevertheless, the eruption touched a chord.

Now the doyen of opera critics Conrad L. Osborne has weighed in, and at impressive length, on the subject.

Conrad writes: The inconvenient thing, though, is that slapdash and rash though they sometimes are, “This Is Opera’s” arguments are, broadly speaking, correct….

With this as cautionary background, let me turn to the work of Nézet-Séguin with the Juilliard singers, all striving for the best without greatvoiced models before them…

Read here.

The University of Berlin is in mourning for one of its foremost musicologists.

Professor Rudolf Stephan was the author of several interpretative texts on Mahler’s music and an influence on its German reception. He was also a keen advocate of contemporary music and a rigorous teacher who required his students to read at least 200 pages a fad.

This is conductor/pianist Daniel Barenboim (Staatskapelle Berlin) rehearsing Rach 3 today with conductor/pianist Lahav Shani (Rotterdam Phil, Israel Phil).

Looks like they’re getting on.

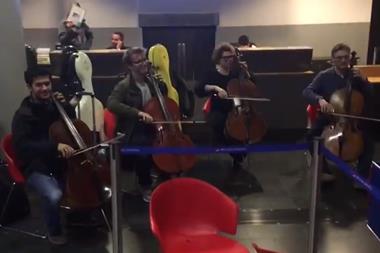

From Gabriella Swallow:

We are currently stranded at Basel Airport because of British Airways total incompetence checking in Cellos …there is only one thing to do to highlight this. Come on Britishairways.com please stop this travel nightmare for us Cellists. Currently stranded at Basel and just want to get home. This is totally unacceptable.

In today’s Times, Willie Walsh of IAG, which owns BA, claimed the brand is damage-proof. Hmmm… let’s see about that.

The DSO Berlin has been forced to cancel tomorrow’s concert in Seoul, South Korea.

It is in Tokyo, where all flights are grounded by the typhoon.

Its manager Alexander Steinnbeis tells Slipped Disc: ‘We were caught right in the middle of typhoon Hagibis which resulted in a cancellation of our onward flight connection from Tokyo to Seoul this afternoon. Finding alternative connections for 115 people is proving very difficult, as flights are hugely disrupted. The first concert in Seoul therefore has had to be canceled and the second one is in jeopardy as well, although we are still hoping to make it there.’

Joseph Horowitz asks the question in a 4,000-word review of the Met production and offers no answer.

What he does highlight is how offensive the opera can appear to African-Americans.

He writes: James Baldwin in a 1959 essay in Commentary liked both the novella and the opera. “DuBose Heyward loved the people he was writing about,” Baldwin opined. And Porgy and Bess—“until Mr. Preminger got his hands on it”—was “an extraordinarily vivid, good-natured, and sometimes moving show.” Baldwin’s complaint about the characters (shared by Lorraine Hansberry) was that they embody “a white man’s vision of Negro life,” that they “veer off into the melodramatic and the exotic,” that—a form of envy more germane to Heyward’s psyche than to Gershwin’s—they seem to speak “of a better life—better in the sense of being more honest, more open, and more free: in a word more sexual.” That is why “Americans are so proud of the opera—it assuages their guilt about Negroes and attacks none of their fantasies.”

But what if Gershwin was not writing about ‘Negroes’ at all? What if he had other folk in mind?

That’s a suggestion that I have just pursued in Genius and Anxiety.

It opens up new avenues of inquiry.

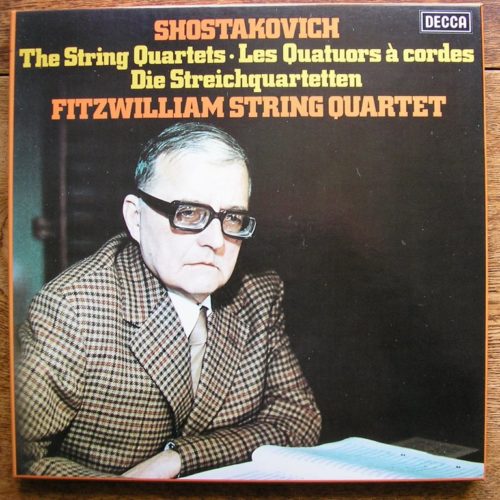

Alan George of the Fitzwilliam Quartet has been reflecting on playing a great modern cycle from the time of its inception until now. Music history in the making:

The Shostakovich connection goes back to our first year in Cambridge; those of us who were there then as students gave our first public concert outside Cambridge in June 1969, which saw us playing No. 8. This was kind of on the cards from the beginning; three of us were in the National Youth Orchestra, and got together to form a string quartet in Cambridge as soon as we arrived. We were all violinists, so I had to change to the viola! We’d done the Tenth Symphony in our last concert with the NYO and it rather infected us, so playing the quartets seemed the natural thing. So after that, while still at Cambridge, we just learned a few more; hardly any of them were played in the West apart from No. 8. We were so lucky to be able to go straight from undergrads at Cambridge to being the Quartet in Residence at the University of York, and we brought it all up here with us.

There used to be a place called the Anglo-Russian Music Shop, next to Foyle’s, and one day I saw an LP of Quartet No. 13, which I had no idea existed; I bought it and listened to it, and it just blew me away, so we decided we’d like to play it. But there wasn’t any music available, so a good student friend of mine (the writer Erik Levi) suggested that we write to Shostakovich. I got an immediate reply from him saying that when he got back to Moscow he would send the music and that he was going to be back in England in November, so if it happened then he would come to hear it. It was really rather a bombshell – we had had no expectation of anything like that, as I didn’t even know that he was coming back to Britain again. Sure enough, a few weeks later the music arrived with another letter, saying he still hoped to be able to come. I had a phone call from the Hochhausers, who were managing him at the time, informing me what train he was going to be on and what kind of accommodation he’d need; we got the university to fix everything up and I went and met him from the train, and it was as straightforward as that! It was unbelievable, life-changing in a way. Every time I walk to the station it keeps that memory fresh: I don’t go up to the university that much any more, but just being in that hall is enough for me to picture exactly where he sat.

And it all developed from there; Decca wanted us to go on and record the whole lot, and I’m glad to say the recordings did get a bit better over the course of that project and we got some very good reviews which led to the label asking us to do even more. In many ways we were running before we could walk; we’d come out of Cambridge and gone straight into this amazing residency at York that had enabled us to rehearse, do concerts and find our feet; but with the Decca contract under our belts we were always struggling to keep up, both with the recordings and with the reputation we were forming. It was quite tough, actually, and it put a lot of strain on us for a while. But the origin of it all was just being in the right place at the right time.

Read on here.