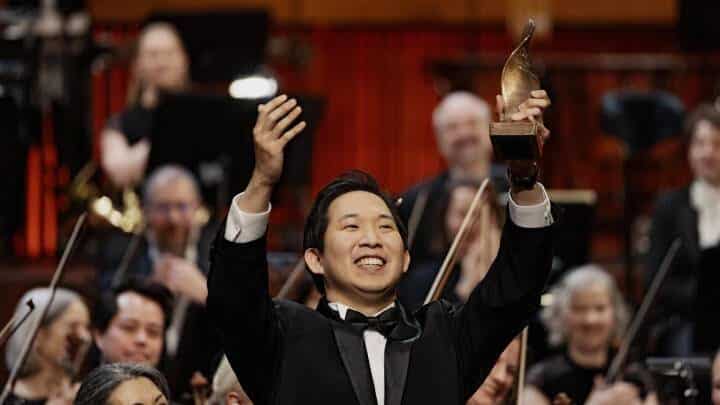

Why I’m conducting the unofficial Mahler First

mainYou may have read about the furore concerning a rival edition of Mahler’s First Symphony. Kenneth Woods is down to conduct its premiere. Here’s why:

I was once asked to go on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme to debate the tempo of the third movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with Sir Nicholas Kenyon. I can still remember the host, Evan Davis, sniggering that this was an entirely silly topic. Musical controversies are, by and large, tempests in teapots. Evan’s first question was simple – “Does any of this really matter?”

Nevertheless, there seems to be a proper musical controversy raging now regarding the publication of the new Critical Edition of the Mahler Symphonies Breitkopf & Härtel, which is being launched in celebration of the 300th Anniversary of the world’s oldest music publishing firm. It has been edited by Christian Rudolf Riedel with additional contributions from Constantin Floros.

The release of the first volume has been greeted with dismay by the publishers of the existing Critical Edition produced by the International Gustav Mahler Society (IGMG) in Vienna, who have posted a statement about the Breitkopf on their website which states in part:

“…the planned publication by Breitkopf & Härtel is not being undertaken with the cooperation with the IGMG and apparently does not meet the requirements of a modern scholarly, critical edition… [it] claims to be based on the “old” Gustav Mahler complete edition, which was produced by the IGMG beginning in the 1960s. This is now being replaced by the NKG, the New Critical Complete Edition, its creation spurred by the realization that the discovery of numerous new musical sources had left previous research outdated. On the other hand, the approach of the publisher Breitkopf & Härtel seems to be to reproduce the old complete edition using computer engraving, but apparently without systematic research using all of the now available source material.”

On the 19th of May, I will be conducting the world premiere of the new Breitkopf & Härtel edition at Colorado MahlerFest. Among MahlerFest’s many achievements, its most prized is the Gold Medal of the IGMG. We are one of only two American organisations to have received it (the other is Mahler’s own orchestra, the New York Philharmonic), and so it should be obvious that we enthusiastically support all the work of the IGMG, including their work on the NKG.

So, why court controversy by introducing this new edition? Our decision was based on a balance of the festival’s ethos and pragmatic considerations for our musicians and librarians.

Since its founding thirty-two years ago by my predecessor, Robert Olson, MahlerFest has always tried to be at the forefront of Mahler scholarship and performance. The festival took great pride in giving the world premiere of the Joseph Wheeler version of Mahler’s 10th Symphony in 1997, in preparation for which Robert Olson and a small international team of Mahler scholars spent over a year editing and preparing. This undertaking did not in any way represent a rejection of the better-known Cooke Performing Version. In fact, in 2017, we also gave the first performance of the Cooke to incorporate the latest revisions from Colin Matthews, David Matthews and Peter Wadl. No other North American organisation has performed as wide a range of Mahler’s music as we have. We have already done the existing IGMG version of the First and the five-movement Hamburg version; unveiling this new version is a logical next step for us.

As the IGMG statement notes, the new Breitkopf edition is based on the ‘old’ Complete Works edition. This is not, I think, a controversial approach. Most scholarly editions include a Critical Report (as does this one) which summarises the changes made from previous editions. So it is here. The preface to the new score notes that “Without fundamentally questioning the Complete Critical Edition… a large number of clarifications in the music text could be obtained, editorial inconsistencies rectified, and errors corrected that were discovered in the meantime.”

The IGMG’s first Critical Edition of Mahler 1 was edited by Erwin Ratz and published in 1967. A second edition followed from Sander Wilkens in 1992, corrected in 1995. I have always conducted Mahler 1 from the otherwise excellent Wilkens score, which is most famous for incorporating one of musicology’s worst all-time own goals: it wrongly asserting that the famous bass solo in the third movement was meant to be played by the whole section. The IGMG’s former editor in chief Reinhold Kubik went so far as to say this “exposed the Critical Edition to ridicule from all Mahler researchers….”

In his Critical Report to the new Breitkopf edition, Riedel notes that “Ratz was able to rectify many errors in the music[al] text…. The editorial report printed there gives, though, hardly any information about the sources used and the editorial decisions… [and] that a whole range of sources had still not become known or had still not been examined at the time. It was only with his “improved edition” in 1992 that Sander Wilkens shed more light on the transmission of the sources….” The new Breitkopf edition is by no means a simple re-setting of the old Ratz edition, or for that matter, Wilkens, but is heavily indebted to the work of leading Mahler scholar, Paul Banks and his online works’ catalogue, The Music of Gustav Mahler: A Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Sources, which, according to Riedel, “details source provenance, chronology and dependencies… The sources evaluation of the present edition is largely based on Paul Banks’ research findings”

So, what we have here is an attempt by Riedel and his team to produce an edition which incorporates the most comprehensive assessment and evaluation of all the extant sources which has been possible in the generation since the publication of Wilkens’ score. All that remains is to test their work in the laboratory of the concert hall. MahlerFest, which offers both a platform and scrutiny, is the perfect atmosphere in which to unveil a new edition, because we have a community of astute Mahlerians among our audience who will be scouring the Breitkopf for every new slur or removed accent… or mistake.

From a pragmatic point of view, the new edition has a lot going for it. The score and parts, which are elegantly typeset, are printed on sturdy paper in a large format and are easier to read than existing editions.

Each part includes a fold-out with translations of all of Mahler’s German terminology. Perhaps most importantly, while the parts for both the Complete Works Edition and the NKG have always been available only for hire, the new Breitkopf parts are for sale. Preparing parts of a Mahler symphony for performance, including marking bowings, is a time-consuming and expensive process. Orchestras’ libraries of marked parts represent an important repository of institutional knowledge, and we find it hard to accept using rental parts of standard repertoire pieces, knowing that all the work putting into the parts in preparation for this year’s performance will be lost, and that next time we do the piece, we’ll have to hire another faceless, or possibly de-faced rental set (there is nothing more aggravating than paying $2000 to rent a piece and it showing up looking like it has lined an animal cage). In his preface, editor Riedel notes that his team were interested in “pursuing primarily practical matters.” In this respect, I think they have hit the ball out of the park.

I can understand the consternation of our colleagues at the IGMG, many of whom are long-time friends of MahlerFest and have spoken at our symposium. They take their role as guardians of Mahler’s legacy very seriously. For perspective, however, I note the hopeful case study of the publishing house long considered the guardians of Beethoven’s legacy, then displaced by a disrupter. For 150 years, there was only one definitive edition for the Beethoven symphonies. Then, in 1984, a young British musicologist and conductor named Jonathan Del Mar started work on a new edition that would challenge 150 years of tradition and precedent. Of course, the publishers who had guarded Beethoven’s symphonic legacy for so long were Breitkopf, the Beethoven establishment of yesteryear, now recast as today’s Mahlerian upstarts. Del Mar’s spurred a new generation of Beethoven recordings and fresh thinking about Beethoven’s music. Breitkopf had already begun work on their own new Urtext Edition of the Beethoven symphonies edited by Peter Hauschild and Clive Brown when Del Mar’s edition arrived, so the parallels to the Mahler situation is obvious. In the end, when there are complimentary scholarly editions available, performers and listeners can only benefit. The IGMG’s new edition of Mahler 1 is slated for release later this year, and I plan to buy a copy the day it comes out. Debate and discussion makes the world go round, we can all use more of it.

I’ve only had my Breitkopf score for a couple of weeks. In time, I expect many interesting discoveries, and I know that, with this being a first printing, we’ll find some very funny mistakes that have slipped through. What I hope, however, is that as the project unfolds, we can answer Evan Davis’ pithy question “Does any of this really matter?” in the affirmative.

Kenneth Woods is the Artistic Director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra

www.mahlerfest.org

www.kennethwoods.net

Good and thoughtful article. I think we the public often don’t know the story behind many pieces and do not know how often they have been changed, re-orchestrated etc.. Moussorgsky’s lovely, Pictures at an Exhibition, for example, was composed only for piano; and later re- orchestrated by many people. The most famous version (but only one of many) is by Ravel.

I’m glad that Maestro Woods has gone into the extensive background of this Mahler work. He has done a service to the public.

“All that remains is to test their work in the laboratory of the concert hall.”

Is musicology really testable in the sense that the ear will decide?

That is, if an editor cites some source (let’s say a note in Mahler’s own hand) that says the solo bass should be played by the whole section, it isn’t the ear that determines the validity of the edit, it is other scholars independently evaluating the cited source and deciding its validity.

(By the way, are scholarly editions of scores like scholarly editions of texts, in that everything is footnoted with the source material, allowing scholars to consult it?)

It depends. Some scores have extensive documentation. For example, the Del Mar edition of the Beethoven symphonies and string quartets for Bärenreiter offers entire books of notes on the editorial decisions made, describing the sources, etc. Henle in many recent editions has done similar things, though not quite in the same level of detail. But if you get a “critical edition” score of some other work, you may simply have to take their word for it that they made the right choices, because no explanation is provided.

I’ve found reading the Del Mar critical notes to be quite informative even in a general sense, not just about the reason for the dot on the 3rd note in measure 26. His explanations of why particular choices were made have revealed many things that I didn’t know about Beethoven’s compositional process. They aren’t volumes that you would read in isolation, but going through the score with them has never been less than fascinating for me. Your mileage may vary.

The third mvt. Bass solo was played using the entire section years ago in my orchestra, and I took part in this unusual event which the conductor firmly insisted upon. No matter what the discrepancies are concerning the ambiguity as to how many performers Mahler wanted, the result was laughable to all of us. One bass is sufficient, whatever our scholars say.

I’m left with new-found respect for Evan Davis.

The maestro doth protest too much, methinks. He comes across as a shill for Breitkopf. While he gives reasonable practical reasons for performing the new edition, he gives no MUSICAL reason for including the Blumine movement in the context of a performance of Breitkopf’s Fassung-letzter-Hand version of Mahler 1st. I hope Blumine will be treated as it is in the edition, as an appendix, and be separated from the symphony (where it doesn’t belong for many reasons) either by the intermission or as an encore after the symphony. Blumine only makes musical sense as part of the symphony itself in the context of the original version of the score. The IGMG says its publication of the original version is scheduled for “early 2019” (Frühjahr 2019).

On the other hand, I do like to cite proper performance-practice behavior when I find it and must give Woods credit and encouragement for finally seating the strings of the Mahlerfest orchestra in proper Mahlerian fashion (split violins, cellos left, violas right), at least to go by the YouTube videos I’ve found. Every photograph of Mahler in front of an orchestra shows this layout (the universal, standard arrangement by 1900) and it is musically far superior to any other layout for music around this period. Mahler even discussed this with Natalie Bauer-Lechner as recounted in her fascinating book. People, and the IGMG, get bent out of shape discussing the order of the movements in Mahler 6th, a debate affecting at most one symphony, while the disposition of the strings influences important musical values in every bar where they are playing in every single orchestral piece by Mahler. It is a far bigger issue than two movements in the 6th or Blumine. There are several Mahler Symphony recording cycles now underway that still don’t seem to understand that Mahler (as well as Strauss, Elgar, Bruckner, Dvorak, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Debussy, Ravel etc.) composed specifically for this arrangement.

It’s amazing, isn’t it? I’m in danger of getting a bit obsessive about the stupidity of not separating, certainly up to about 1900….

To my horror, I once heard a recording of the Handel Opus 6 Concerti Grossi with both sets of fiddles on the conductor’s left!!!!!!!!! (For the avoidance of doubt, it wasn’t the Karajan version.)

Hi Sixtus

I give no reason for the inclusion of Blumine because it is not included. There seems to a misunderstanding here. Breitkopf have published separate sets of scores and parts for the 1st Symphony and Blumine, and at no point have they or their editor suggested the inclusion of Blumine as part of the First.

They have included Blumine in their hard-bound collectors edition of the score of Mahler1 because there could not otherwise be any commercial justification for printing Blumine, which is only a few pages long in full score. When we premiere both editions at Colorado MahlerFest, we will be presenting them as separate pieces, which I believe is what the Breitkopf team would think is the ideal approach (although I would absolutely not presume to speak for them).

We’ll perform Blumine as a little amuse-bouche at the beginning of the second half, followed by the symphony. It is tempting to do Blumine as an encore until you consider that one’s principal trumpet will be half dead, with lips that feel like they’ve been danced on by elephants by the end of the symphony.

I do always do Mahler with the violins on opposite sides of the stage whenever it is possible. Likewise for Elgar, Brahms, Beethoven and Schumann, and often Mozart. It depends on the venue, the wishes of the orchestra and the acoustic, but my preference for this seating arrangement is strong.

Finally, I may come across as a shill, but I can assure you that these days, the stakes in our industry are sufficiently low that one can afford to speak one’s mind. I’m a dues-paying member of the IGMG and own all their scores. The passion and dedication of the folks who work on Mahler means that these things are often presented in passionate terms. After my MahlerFest debut in 2016, I had a long chat with the current editor-in-chief of the IGMG, who was talking about the shortcomings in the recent NKG editions and how recent research and newly-found sources meant a new edition of the Fifth Symphony was needed, in spite of the fact that the most recent score was only a few years old at that point.

Thanks for reading

Ken

Sorry… that sent one sentence too early. The point of my remarks about the 5th should be self-evident. The nature of research and scholarship is that our findings are always changing. One shouldn’t be too in love with the received wisdom we grew up with, nor too over-excited about the importance of the latest finding.

“One shouldn’t be too in love with the received wisdom we grew up with, nor too over-excited about the importance of the latest finding.”

That’s a heck of a nihilistic view of Mahler: whatever you hear, it’s not quite what he intended…

1) I’m naturally suspect of “tradition”, it’s unscientific, non-verifiable, and can easily get corrupted, but surely there must be players still alive who was a student of a student of a student of someone who played under Mahler to say that “this” was how my teacher said he learned to play it from Mahler himself?

2) How much is there left to unearth?