Enigma Variations solved? Oh, not again….

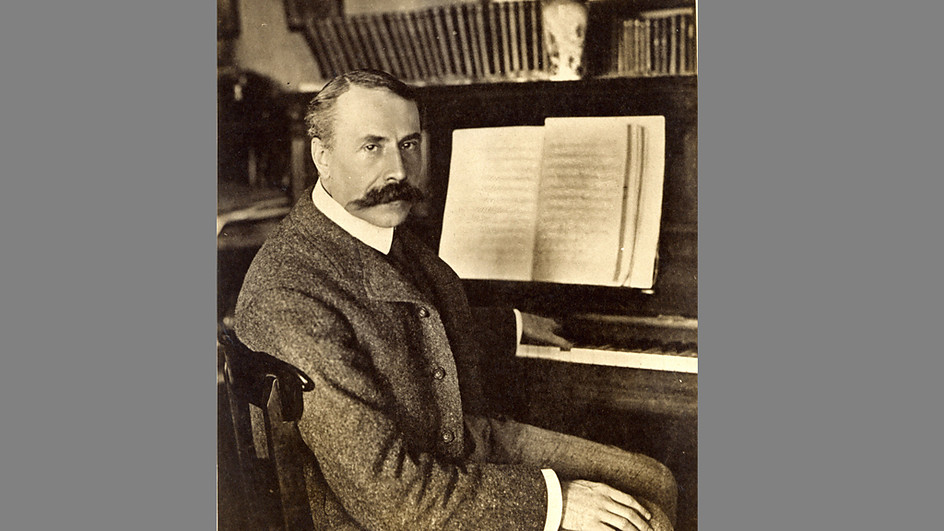

mainThere has been very little reaction to an explosive claim in the Times this weekend by ‘one of the country’s sharpest young musical minds’ that he had cracked the riddle at the heart of Edward Elgar’s breakthrough work.

According to Ed Newton-Rex, 31 – ‘a composer and artificial intelligence music expert who obtained a double starred first in music from Cambridge, graduating top of his year’ – it’s a tune from Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater.

Some are persuaded.

Most are not bothered – any more than they were three months ago when a laughing policeman – ‘a police inspector with an MA in crime patterns’ – told the Daily Telegraph that he had cracked the code, albeit with an unfathomable solution.

Or the Leeds professor who discovered in 2015 that it was a well-known hymn.

All good theories. None matters much any more.

In 1985, when Elgar’s godson disclosed to me the name of the composer’s long-lost girfriend, the story made the front page of the Sunday Time and we were bombarded for weeks afterwards with clues as to the lady’s whereabouts.

That was then. Today, classical music is a peripheral pursuit and the mass media no longer carry critical mass.

Sad but true.

The music endures.

Whatever brilliant solutions emerge, only Elgar knows the truth, so we’ll never know, unless some documentary evidence comes to light, which is unlikely.

Indeed! In the meantime, we can keep enjoying this wonderful music, even without knowing the riddle. Norman Lebrecht was right: “The music endures”.

His explanation is highly convincing.

Amen!

“Explosive claim”? About a 120 year old piece of music that the vast majority of humans have never heard? It’s not even explosive in the niche world of Classical music.

A piece loved primarily in the UK. US orchestra musicians often refer to it as the Enema Variations.

No American composer ever produced such a masterpiece.

At very least I’d put Copland’s Appalachian Spring right up there with Enigma.

Sam Barber had a few…

I am in the US, love the piece, and have never heard any of my musician friends refer to it in that way.

The discography of this famous work includes plenty of major non British conductors and orchestras.

I once came across a live recording of the Cleveland Orchestra under William Steinberg. I loved it. Nobody forced me to listen to it, but I couldn’t turn off the youtube clip.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cXPp-iYL0D8

I try not to listen…getting Nimrod out of my head–much as I like it–is nearly impossible.

Nimrod is one of those masterpieces that are so overplayed, that we roll our eyes instead appreciating their beauty. I feel the same way about Barber’s Adagio, Mozart’s Little Night Music, even the Ode to Joy.

It’s a frequent inclusion on the programmes of many orchestras in Canada and as far as I know is very well-liked here. As it should be.

Here’s another one for you Norman. Personally, I’ll stick with the Mozart “Prague” Symphony theory.

https://newrepublic.com/article/139816/breaking-elgars-enigma?mc_cid=d439ddf40c&mc_eid=63cc4302ca

“Enigma Variations” is a masterpiece, possibly Elgar’s greatest work.

I, for one, have no interest whatsoever concerning where Elgar came up with his inspiration.

I only know that the beauty and profundity of Nimrod makes me cry every time I hear it.

Every. Single. Time.

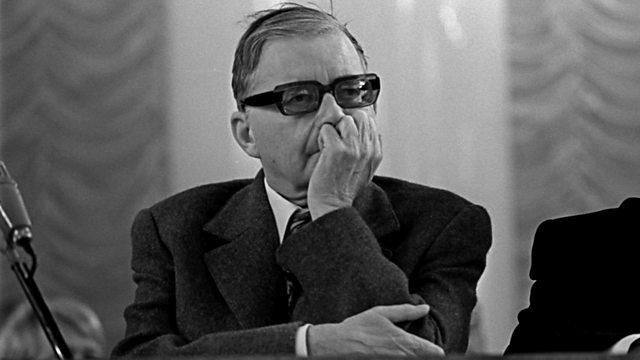

A meticulous assessment of Pergolesi’s ‘Stabat Mater’ confirms that melody fails to satisfy five of six criteria provided by Elgar. The British media’s repeated attempts to prop up a non-German solution proffered by students of English institutions is admirable but misguided. The absent Theme is German in origin, a critical clue affirmed by the Theme’s German title (Enigma is spelled the same in German as it is in English), Elgar’s German rendering of his first name for the Finale (E.D.U.ard), and four melodic quotations in Variation XIII from a German composer’s concert overture with the original German title ‘Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt.’ To learn more about this surprising melodic solution, read my 37-page paper cited by Wikipedia, ‘Evidence for Ein feste Burg as the Covert Theme to Elgar’s Enigma Variations.’

http://enigmathemeunmasked.blogspot.com/2016/04/evidence-for-ein-feste-burg-as-covert.html

Mendelssohn’s version of Luther’s well-known hymn “Ein feste Burg” (A Mighty Fortress) plays “through and over” Variation IX Nimrod in the following audiovisual demonstration:

https://youtu.be/myjjfkJ27cw

This contrapuntal mapping affirms the identity of the covert melody to Elgar’s Enigma Variations. To learn more, visit http://enigmathemeunmasked.blogspot.com/2010/09/variation-ix-nimrod-with-ein-feste-burg.html

Elgar advised in the program note for the June 1899 premiere of his ‘Enigma’ Variations, “So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.”

It is decidedly odd that in his description of a symphonic work dedicated to his friends, Elgar refers to the Belgian playwright Maeterlinck by name and two of his plays (L’Intruse and Les sept Princesses). This is clearly anomalous as Maeterlinck was a stranger when Elgar composed the Variations in 1898-99.

Elgar’s conspicuous phrase “Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’” is bracketed by dashes and exhibits some intriguing attributes. For example, when distilled down to its discrete initials, it presents a reverse spelling of PSALM. This acrostic anagram is highly reminiscent of another within the performance directions of the Enigma Theme’s opening measure that also spells PSALM.

The phrase “Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’” has exactly 46 characters. That same phrase spells psalm in reverse as an acrostic anagram. Consequently, Elgar’s anomalous reference to Maeterlink and two of his plays encodes both the word psalm and the number 46. The title of the covert Theme originates from the first line of Psalm 46. Observe that the first two initials of that phrase are ML, the same as those for the composer of ‘Ein feste Burg’, Martin Luther.

Now here’s the pièce de résistance. Elgar was English, Maeterlink was Belgian and his plays are written in French. These three nationalities are listed below:

English

French

Belgian

Do you notice anything remarkable about the initials of those three nationalities? It’s an acrostic anagram of ‘Ein feste Burg.’

It is extraordinary that the word psalm, the number 46, and the initials for Martin Luther and his hymn ‘Ein feste Burg’ are all compactly enciphered within the precise section of Elgar’s program note that specifically addresses the subject of the absent Principal Theme. My cryptographic research confirms that the answer is encoded within the question. I discuss these findings in my recently released article ‘Elgar’s Maeterlinck Enigma Ciphers.’