Fascinating clip from an excavated BBC documentary in the days when not everything had to be explained for a non-existent mass audience.

Fascinating clip from an excavated BBC documentary in the days when not everything had to be explained for a non-existent mass audience.

1 Mozart piano concert 27, K595 (Brendel)

2 Vivaldi Four Seasons, 1958 L’Oiseau Lyre

3 Elgar: Enigma Variations, with Sospiri

4 Barber Adagio

5 Mozart Requiem

6 Cosi fan tutte

7 Handel Messiah

8 Rossini: Messe solonelle

9 Schumann symphonies (SWR Stuttgart)

10 Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue (Philharmonia)

I am sitting in our favourite Kensington lunch place waiting for Neville when he breezes in, carrying a bulging briefcase that has seen better days. ‘So sorry I’m late,’ says Neville, who isn’t. But he is always courteous and considerate and if he sees me sitting down he assumes he must have been at fault.

‘What’s in the bag, Neville?’ I ask.

‘Oh, a Walton symphony,’ he says.

‘Not really your thing.’

‘Never done it before. Was studying it on the Eurostar this morning.’

‘Neville,’ I exclaim, ‘You’re 90 years old… what are you doing learning new pieces?’

‘Oh, a friend is starting a new orchestra and desperately needed someone to conduct it. I couldn’t really say no.’

That was Neville through and through, the man who would never let a friend down, who took every work of music on its merits and remained ever curious as to what a new score might contain.

Once we got talking, the food could wait. He might remember trying to get Elisabeth Schwarzkopf to follow his beat, or how he joined the Philharmonia intifada against Herbert von Karajan, or something that Alfed Brendel had just showed him in a Mozart manuscript. He was an irrepressible fount of memory but, unlike so many others, he was both modest in his own part in the story and deeply interested in the person he was talking to – me, in this instance.

I once asked him how he suffered the war wound that landed him in a hospital bed next to Thurston Dart, the mathematician who first showed Neville the possibilities of period pitch and tempo. We were sitting in his Kensington flat. It was a summer evening and there was an empty bottle of red wine on the coffee table between us. I said very little and let Neville talk.

Soon, we were in pitch darkness. I looked around to find a light switch and saw Molly, his wife, hovering at the door, signalling me not to move. Neville had been part of an advance party that recce’d the Normandy beaches a few days before D-Day and was lucky to get out alive. Molly had never heard the story before. Neville was too modest to let on. (In some versions of his life he said he was invalided out by a kidney ailment; the ailment was sharpnel and he spent months in hospital.)

He loved orchestras, couldn’t get enough of their gossip and intrigues while always respecting the players’ craft and commitment and never indulging in malice. Those who fell out with him – Christopher Hogwood, for instance – found themselves embraced in reconciliation. So many musicians, down in the dumps, were picked up and set on their feet again by the ever-patient Neville. I can’t believe he is gone.

The last time I saw him, he was working around the corner at Abbey Road and I decided to drop in and surprise him. His face lit up at the sight of me and he made me promise to stay ‘for a bite of lunch’.

It was a commercial session with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, paid for by the soloist. After a couple of decent takes, good enough for a commercial job, Neville tapped his baton on the stand and said, ‘I think we can do better than that, don’t you?’

Backs straightened in the orchestra, pages were turned back in the score.The next take was a manifold improvement. That was Neville: ‘I think we can do better than that.’

May his dear soul find eternal rest.

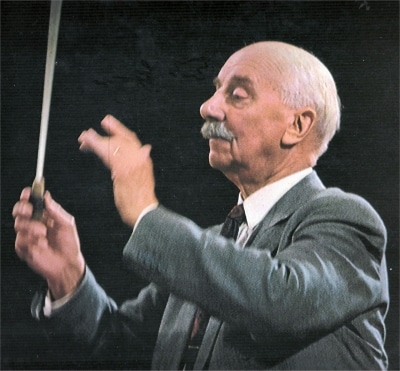

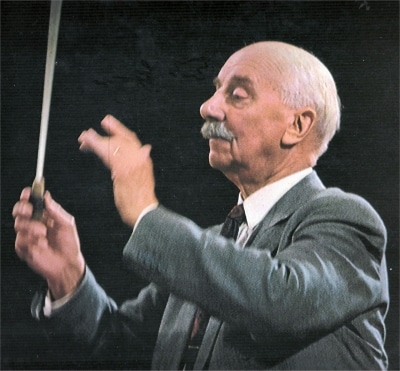

The Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto have posted pictures of Neville conducting them on Thursday, sprightly as ever at 92, totally at one with his musicians.

Two days later, he breathed his last.

This is how we should remember him.

The most prolific English conductor – he made more recordings than anyone except Herbert von Karajan – died last night, October 2, peacefully at the age of 92.

He and I were friends for many years, close for the last decade.

I will shortly write a personal reminiscence.

Meantime, the bare facts.

Born on 15 April 1924 in the cathedral town of Lincoln, he was summoned into the London Symphony Orchestra when most of its violinists were conscripted into the army in 1939. Neville was just 15.

He was the last active musician to have played for Henry Wood, Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler and other giants of the first half of the 20th century. He absorbed much from observing them.

The one who spotted his potential as a conductor was Pierre Monteux, whom he always named as his teacher and mentor.

Neville became interested in historically informed performance while recovering from war wounds in 1944. He founded the Academy of St Martin in the Fields in the mid-1950s and turned it into the most sweet-sounding of the many bands that purported to play baroque and early classical music at original pitch and tempi – though never on original instruments.

He was the kindest, most considerate of men, absolutely beloved of his players. If a musician was ever in trouble, he would drop everything until the matter was sorted. He once told the Musikvereinsaal management in Vienna, is the most polite and reasonable way, that there was no possibility of an Academy concert the next day unless one of his violinists, a Slovak refugee on temporary papers, was released immediately by the border authorities. The player was back in his seat within the hour.

In the 1980s, Neville was music director with large orchestras – the Minnesota Orchestra and SWR radio orchestra in Stuttgart. He adored the big noise they made, but was always happiest with his Academy.

He was knighted for services to music, becoming Sir Neville in 1985. Last year he received the rare and signal honour of being named Companion of Honour (CH). He received these gifts with his customary humility.

Devoted to Molly and their family, he liked in recent years to avoid conducting in the summer when, as he put it, ‘the garden needed me’. But he could never turn down a request from a friend and he was travelling the world busily to the end. He conducted for the last time on Thursday, at Padova in Italy.

He was, I think, the least self-regarding musician I have ever known. I loved him deeply.

UPDATE: Glimpses of Neville

UPDATE2: The indispensable recordings.

Tobias Richter, Director-general of the Grand Théâtre de Genève, has announced he will leave in 2019, when he reaches retirement age.

Geneva has become something of an operatic backwater, but the job is well paid and the budgets are respectable. In the 1980s it was the launchpad for Hugues Gall’s career.

They should be talking to Kasper Holten and John Berry, while stocks last.

Anthea Kreston, American violinist in the Artemis Quartet, discovers that, to paraphrase L. P. Hartley, Germany ‘is a foreign country:they do things differently there’. Here’s her weekly diary entry for slippedisc.com

We have begun concerts on our new repertoire. What a civilized way to begin – with 2 “house” concerts in Berlin, then on to our regular touring schedule, which begins this week. Last night, we played in the ballroom of the Savoy Hotel in Berlin. Shimmering chandeliers shed light on the opulent wood and burgundy of the room, while guests sat at tables, their place settings meticulously set (I immediately thought of Downton Abbey and the precision of the measuring of wine/water/aperitif glasses).

This was a special occasion – the evening marked an anniversary of the parents of the cellist of the Artemis, and friends came from near and far to celebrate. Children had their own table (complete with fabric place cards, miniature paper castles filled with treats, and coloring books), and the Artemis concert was preceded by a verbal welcoming of certain guests, and their ties to the family (the elder Runge’s are retired diplomats, and their stations spanned the continents).

Playing for the public for the first time after intense, endlessly scrutinizing work, is an odd experience. The mind is over-sensitized – split between recollections of minutia, personal technique, expressive desires and communication with the quartet and audience. Funny things happen – I forget a bowing, and then notice someone else has compensated at the same moment that I get back on track. I look eagerly towards a colleague at the same moment they look towards me – which of us was supposed to cue that one? A funny smile contagiously spreads across the quartet as a member FINALLY remembers that repeat. I go in and out of being incredibly aware of how out of tune I am, then refocus on vibrato or bow speed, or even – wait – did I just do a bizarre knee bend for some reason? As a glasses-wearer (I used to wear contacts, but one time I had dry eyes and lost a contact early on – and spent the remainder of the concert in a semi-fog – after which I switched permanently to glasses), I slowly recognize the rests when I have enough time to push them up again, or which movement warrants more glasses or hair maintenance.

After our performance, the quartet (and their families) are seated and I have the chance to be with the girls. Jason is off to Hamburg for a concert of his own (leaving yesterday at 7 am and arriving back today in the wee hours). As he begins to be more integrated into Berlin, our web of schedule becomes more complex – the need for outside help once again is a part of our lives. We have been in a cocoon for these 8 months, but now, as we begin to transition once again into a two-income house, a support network is beginning.

This week, both Jason and I were rehearsing at the University of the Arts – me with Artemis, and Jason directly below with a small, conductor-less chamber orchestra, lead by an old friend of mine from Curtis, the incredible Indira Koch (concertmaster of the Deutsche Oper Berlin). To go down to Joseph’s for a cappuccino break, and see Jason at a full table of musicians, laughing and talking, just made my day.

On another note, we have begun to host parties here. I love to have people over, and I am finally out of party hibernation. First a breakfast for our daughter’s friend and family, then a party for musicians (it was a beer and nacho party), and coming up our daughter’s entire first grade will be coming over for a potluck and clothing swap. A house full of guests this week (5 from Oregon), then a couple of days alone before my sister, husband and daughter come for 10 days. It begins to remind me of Oregon, when we were rarely alone in our homes – a revolving door of students, rehearsals, family and friends.

He’s coming to Sydney. Watch out for the Rupert Murdoch jibe.

Matt Groening in conversation with Lynda Barry: Love, Hate & Comics

WHEN: Saturday 5 November 2016, 4.00pm

WHERE: GRAPHIC – Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

TICKETS: graphic.sydneyoperahouse.com/matt-groening-and-lynda-barry/