Living the life of Pal Joey

mainChicago pianist Lori Kaufman was among those who were present at Tanglewood’s farewell to Joseph Silverstein, much-loved concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and, later, music director of the Utah Symphony. Joey, who died last November, aged 83, Joey was always so much more than the sum of his titles.

Lori writes:

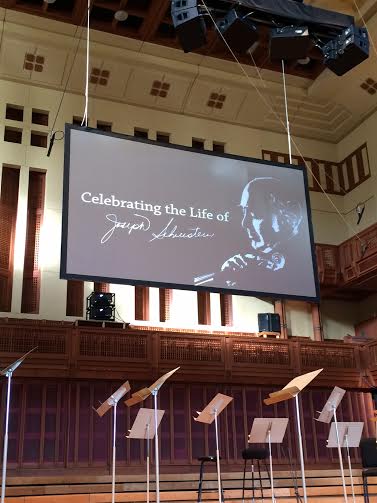

Over 700 close friends, family members and former students filled Seiji Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood Sunday night for a celebration of the life and gifts of Joseph Silverstein, whose abrupt passing last November left much of the music world bereft. Impeccably curated by Anthony Fogg with input from the Silverstein family” and the Boston Symphony, the evening could not have been a more perfect homage to the achievements of Mr. Silverstein and the impact he had on thousands of musicians of all ages.

To start, twenty-six string players purposefully strode onstage and played the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s exuberant Serenade in C. Impeccably led by Utah Symphony concertmaster Ralph Matson, they performed standing up, as though to bear witness to the legacy that they gratefully bask in every day, many of them still section players in the Boston Symphony. Fred Sherry called Silverstein the “soul of the BSO,” and indeed, his influence on that orchestra and many others will reverberate for generations.

Anthony Fogg, the BSO’s artistic administrator and director of Tanglewood, invited us to “applaud robustly” for the “music that Joey loved and cherished.” Words would not usurp what mattered most to one of the 20th century’s best musicians, so Fogg emphasized that this evening would be full of sounds that would remind us that “our lives were better in some way because of what he gave us.”

Of course the program needed to begin with JS Bach. Silverstein’s recording of the solo sonatas is THE textbook Bach, studied closely by all young violinists. Joey dug deep into every period of violin playing, and his knowledge of the baroque period was unsurpassed. He could justify every bowing and phrasing with historical evidence, and yet still made us hear something new and fresh in each sonata and partita.

Venerable pianists Peter Serkin and Richard Goode then appeared, and their regal performance of three choral preludes by Bach was a master class in four-hand playing. The most elusive of ensemble playing, four-hand music is fraught with sonic landmines around every clumsy corner and demands flawless shading ability and creative sound architecture. These two champions of chamber music voiced the counterpoint luminously, expertly, and with an elegance that is rarely heard today.

Mr. Goode returned to the stage with Curtis Macomber and Fred Sherry to play one of Joey’s favorite movements of all time, the adagio from the Brahms B major trio. I am sure I wasn’t the only one in the audience who was fortunate to have Mr. Silverstein’s coaching on this piece. It was with this very trio that he taught me everything I needed to know about Brahms—- what his unique rhythmic gestures were about, how his eighth notes need to be fat and spread out as looooooong as possible, how his mezzo pianos differ from every other composer’s, how his movements always relate to each other, and how the pianist’s left hand can make or break a performance. Richard Goode is of course one of the few pianists who understands all of these things and his partners helped him send this piece right up to the heavens where it belongs.

The radiant Elena Urioste had the prodigious task of presenting Estrellita. I had the honor of playing this piece with Joey and I’m certain that everyone in attendance had heard Joey play it, even multiple times. Kreisler was one of his most closely studied idols; he cherished those “encore” pieces and snuck them into a recital program whenever he could. Well, Elena got it exactly right, and thankfully her partner Garrick Ohlsson exhibited the color palette and sensitivity to perfectly support the mood of this wistful souvenir. The duo won gasps and murmurs of approval from the audience immediately upon the final arpeggiated chord.

Next we got to hear a recording of Silverstein playing The Russian Dance from Swan Lake while photos of him flickered across a gigantic screen. Graciously, the organizers put aside his most famous photos and let us see many rare mementos of Joey rehearsing, kibitzing, or playfully telling someone off with a glint in his eye.

Late Beethoven was essential to the message of the evening, and it was lovely to hear a set of Joe’s more recent trainees throw themselves into opus 130. The excellent Dover Quartet maintained that Mr Silverstein was “an inspiring presence whose guidance was critical to our development as musicians and colleagues,” and they clearly heeded his lessons well. They glued themselves to each other’s fingerboards and locked eyes with a Joey-worthy focus. Their mentor would have kvelled.

Late Beethoven segued inevitably into Schubert. You can bet that Joey knew every note and every harmony of Schubert’s immense song catalog, as it informed his lyrical playing of his chamber music works and symphonies. Hilary Hahn played a demonically difficult Erlkönig transcription by Heinrich Ernst effortlessly. One of the many musicians who benefited practically since toddlerhood from his generous counsel, he treated her (and so many of us) like additional children to the three biological ones he already had. Hahn obviously inherited his unparalleled work ethic and stunned this audience with her poise and prodigious technique, always and only in service to the music.

The second Schubert piece was also based on a lied, the beloved Trout movement of the eponymous quintet. On hand were some of Joey’s lifelong friends from his hometown of Detroit, the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society, and the Curtis Institute. Ida Kavafian’s love shone through as she conjured the most profoundly poignant trout ever to have swum. This bucolic scene shifted from playful to philosophical in the able hands of Michael Ouzounian, Fred Sherry, Edgar Meyer, and Mr Ohlsson rounding out the stellar quintet.

Between the two Schubert works, we got to hear from four special musicians who wanted very much to attend but sent adoring video messages instead. Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, and Silverstein drank from the same goblet in the elite club of top violinists, and they always shared a loving rivalry between them. To hear Perlman call Joey an “all around consummate musician” surprised nobody, and Zukerman was equally laudatory claiming “The command he had was second to none.”

We then heard from longtime colleague Robert Levin, stuck in Stuttgart but wistfully wishing he was with us. I myself recall so many endearing moments of watching Levin onstage with Joey at Sarasota. An exceptionally erudite scholar, in addition to being a great pianist; for Levin to admit that he was humbled by Joey’s knowledge is telling, indeed. Smartly appreciative of not only their music-making but also their endless conversations, Levin may have had the best description of the night when he called Joey a “radiant humanist.” Joey delighted so much in sharing his knowledge that it made each of us feel like a treasured confidante. And his advice was always so true and so compassionate that it seemed like everything he said was direct from the Torah and deserved an “Amen.” We all found his words so glowing, so valuable, we treated the most random conversations as unforgettable commandments, such as his insistence that bagels needed to be “warmed,” not toasted.

Finally, Andre Previn sent in a lengthy clip regaling us with stunned impressions of their long collaboration. Previn said what many of us saw firsthand, that he never met anyone as musically prepared or as thorough as Joey: “Why was he the greatest concertmaster in the world? Because he made everyone feel secure, he made the orchestra feel secure, and he made the conductor feel secure.” Previn sheepishly admitted that he is still passing off many of Joey’s genius bowings as his own (and he is probably not alone.)

The final live performance of the night brought us full circle back to Brahms. I always felt as though Brahms was the pinnacle for Joey. Those who are serious about chamber music know that the best small ensemble performance ever recorded is the two viola quintets by the Boston Symphony Chamber Players. It has attained cult- like status, and there are certain shifts that Joey did that are listened to and replayed and listened to again late at night at conservatories everywhere. I once asked Joey if there were any performances he wanted to do but never managed to, and he replied that his big regret was never having had the chance to play the Brahms concerto with George Szell. (Obviously that would have been the definitive recording.) On Sunday night, in honor of Joey’s unending love for Brahms, the universe’s pre-eminent duo gave the best performance ever of a violin piece with no violin in sight. Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax drew us in with a devoutly personal Adagio of the d minor violin sonata, cleverly transcribed for Mr Ma’s instrument. Yo-yo is the consummate communicator, always regaling listeners with charming anecdotes and galvanizing stories…. but on this night he had no words. He said everything he needed to say with the look on his face.

But no musician could have ended the evening more conclusively than Joey himself – a brilliant video of his 1972 performance of the Elgar violin concerto with his beloved BSO conducted by Colin Davis. This was a recap of what everyone had alluded to: the incredible command of the instrument, the insatiable investigation of the composer’s style, the flawless phrasing, the “unorthodox” bowing that made the music sound even better than it was conceived, the warm communication (mainly via eyebrows) with his onstage colleagues, the expansive generosity towards his students, the magic that he worked at creating every morning of every day of his life when he would wake up and take out his violin. What came out especially Sunday night was how successful Joey was at each of these roles he inhabited: the perfect concertmaster, a stunning soloist, an all-knowing conductor, a dedicated teacher, a guru of chamber music, a voracious scholar, a treasured counselor to orchestras and soloists and young quartets, a loving father, a devoted husband, a compassionate friend, and an irreplaceable colleague.

The Silverstein family has set up a fund to support violin master classes at Tanglewood. If you would like to honor Joey’s astonishing legacy and join in promoting his love of music, please send your gift (made out to the Boston Symphony Orchestra) to:

Gifts to the Joseph Silverstein TMC Violin Master Class Fund

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Gifts Processing Department

Symphony Hall

301 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, MA 02115

USA

A beautiful description of what must have been a beautiful evening of remembrance. Thanks Lori !!

Sounds truly extraordinary! Clearly a memorable goodbye to a memorable colleague. RIP Maestro Silverstein.

From an old pal of Joey: in the case of “Estrellita” it was the Heifetz influence.