Fascinating confessions on Mumsnet. Full of vital statistics.

Peek in here.

Fascinating confessions on Mumsnet. Full of vital statistics.

Peek in here.

This is major.

It has been announced that Daniil Trifonov, winner of the last-but-one Tchaikovsky Competition, has become a director of the New York Philarmonic.

The rest of the board represent big money. Daniil has all the notes. And a raincoat.

Release below.

Pianist Daniil Trifonov, the 24-year-old Russian pianist who is beginning his final week as the spotlighted soloist in the three-week Rachmaninoff: A Philharmonic Festival, has joined the Board of Directors of the New York Philharmonic, elected on November 13, 2015.

The Philharmonic’s relationship with Daniil Trifonov began with his Philharmonic debut in the 2012–13 season, when, at the age of 21, he performed Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3, led by Music Director Alan Gilbert. The Philharmonic invited Mr. Trifonov to return in the 2014–15 season to perform Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 1, led by Juanjo Mena. Mr. Trifonov is the featured soloist in Rachmaninoff: A Philharmonic Festival, taking place throughout November 2015, in which he performs Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos Nos. 2, 3, and 4 and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, in addition to a chamber program featuring Mr. Trifonov alongside Musicians from the New York Philharmonic.

“Daniil Trifonov will be an outstanding addition to the New York Philharmonic Board of Directors,” said Chairman Oscar S. Schafer. “He is a brilliant pianist who, since his debut in 2012, has thrilled our audiences and established a strong rapport with our musicians that critics and audiences have noticed. His insights as a young musician who travels the world will bring an immensely valuable perspective to the Board at a time of growth and expansion for the Orchestra.” Daniil Trifonov joins Joshua Bell, Yefim Bronfman, and Itzhak Perlman as musicians on the Board with whom the New York Philharmonic has closely collaborated.

The Romanian soprano has launched an appeal for victims of the Bucharest nightclub fire. Among its first supporters is the mass-market Italian tenor, Andrea Bocelli, who sent this message:

My dearests,

I was in the United States, when I heard about the terrible misfortune that has destroyed so many young lives in Bucharest.

That day, I thought about your country, that I love, I visited and which I feel emotionally close, thinking about how much suffering, how much despair had caused this tragedy, involving many families, throwing them in anguish, not denying that, for a moment, my faith threatened to falter. Because in times like these it is so easy to feel disoriented, while searching for a plausible explanation as to why the sky would allow to leave so many young lives without a future.

The existence often puts us dramatically on contradictory aims, and it is heartbreaking to have to admit that the mind of men is not made to understand the logic of God … But He – as a priest told me, a dear friend of mine – has an eternity to make amends, and the time on earth (and any pain it marks the way), is drastically reduced, when compared to perpetual life.

No wonder that a heart as big as that of my dear friend Angela Gheorghiu, has reacted immediately… Unfortunately I can not be physically present at the Romanian Atheneum, but I will be with my heart with you, and pray with you, and I wish to send to the families touched by this tragic event and to all the people of my beloved Romania, my closeness and my most affectionate embrace. ”

Andrea Bocelli

Angela invites everybody to join her efforts to raise funds for all the victims of the fire from Club Colectiv in Bucharest. The collection and distribution of funds are made by Fundatia Pretuieste Viata, led by Andreea Marin.

INTERNATIONAL DONATIONS can be made into the following account:

IBAN : RO13BRDE445SV33742314450

SWIFT: BRDEROBU

BANK: BRD, SUCURSALA DOROBANTI

BANK ADDRESS: CALEA DOROBANTILOR, NR 135, SECTOR 1, BUCURESTI

Word is out that this year’s $100,00 Grawemeyer Award for music composition has gone to Hans Abrahamsen.

The announcement of the award is not due until next Monday but, as we said, word is out.

If there’s such a thing as a happy Dane, Hans is it.

The award is for his song cycle, ‘let me tell you’, with texts by Paul Griffiths.

UPDATE: It appears Musical America has been obliged to take down its leak of this award.

2nd UPDATE: It has just gone live.

LOUISVILLE, Ky., Nov. 24, 2015 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ — let me tell you, a song cycle for soprano and orchestra, has earned Danish composer Hans Abrahamsen the 2016 Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition.

**Note: Due to a news embargo break this information, originally scheduled for Nov. 30 @ 10 p.m., is being announced early**

Abrahamsen’s half-hour work presents a first-person narrative by Ophelia, the tragic noblewoman from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” The libretto by Paul Griffiths is adapted from his 2008 novel—also titled “let me tell you”—and consists of seven poems created using only the minimal vocabulary that Shakespeare originally scripted for Ophelia.

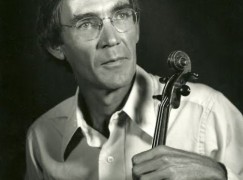

The veteran critic and broadcaster Martin Bookspan has written for Slipped Disc a beautiful memoir of his friend, concertmaster Joseph Silverstein, who died at the weekend.

“Extraordinaire!” That’s the word Charles Munch used when he told me about his newest hire for the violin section of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. And Munch knew a thing or two about playing the violin: he served as Concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Furtwangler from 1926 until 1933. As is customary, the new violinist was assigned the last seat in the last row of the violins. I quickly learned the name of the new member of the orchestra: Joseph Silverstein.

Weeks after the start of the season Mr. Silverstein did what some thought was sheer chutzpah on his part: in a small auditorium in Boston he played a concert of unaccompanied violin works, some Bach as well as the Bartok Sonata. Those of us who were privileged to have attended went back to Munch’s word, “extraordinaire”.

When the orchestra’s venerable Concertmaster, Richard Burgin, announced that he would retire at the end of the 1961-62 season, the floodgates opened for aspirants to succeed him. Among those applying was the young Mr. Silverstein. Another act of chutzpah?

In the meantime I had become friends with Erich Leinsdorf, whose home in Larchmont was a ten-minute drive from mine in Eastchester. When Leinsdorf became the chosen successor to Munch, it fell to him to chose the successor to Burgin. After the auditions were concluded, I received a phone call from Leinsdorf. “It’s Silverstein!” were his first words, before he went on to rave about his chosen second-in-command. By then Silverstein was known to everyone as “Joey”.

In the Fall of 1983 we bought a summer cottage in Stockbridge, minutes away from Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. We formed a little kibbutz: the cottage up the road just before ours was the summer home of the family of Victor Alpert, the beloved librarian of the BSO. And just behind ours was the summer home of Joey and his family. We were a raucous but supremely happy group whenever we got together—which was often!

When I think of him, I remember all those wonderful times we spent together. Rest in Peace, Joey……….

(c) Martin Bookspan/Slipped Disc

The Georgian bass Paata Burchuladze has cleared his diary to run the Georgian Development Fund, which is expected to become a political party. He is also head of a charitable foundation, Iavnana.

‘I never thought of becoming an opera singer, but life brought it to me, or better to say, I was given a chance and I used it,’ he told journalists. ‘I never wanted to be a philanthropist, but life offered me the conditions to become one.’

Next step: government.

The international cellist (l. in picture), a neighbour of ours, wonders why he keeps putting in the hard hours.

A question that my girlfriend Joanna asked me the other day got me thinking. I was preparing the cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas and variations for piano and cello, which I was playing for perhaps the tenth time with Robert Levin on fortepiano; and Joanna wondered what it was that I was focussing on when practising works I know so well. It’s true that I could sit down, not having played any Beethoven for six months, and play any of the pieces almost as accurately as I do in concerts – anyone could, having played them so often.

But that isn’t the point. I do spend a lot of time focussing on intonation, as well as bow articulation – it’s essential, in order to reach a level at which one isn’t distracted by technical problems during performance. Even more vital, though, is to remind oneself of the exact position of every note in the work as a whole. One can read a novel many times, and know the plot pretty well; but will one remember every word? Unless one has a photographic memory, I think that the answer will be no. (And even if one has such a memory, will one remember the true meaning of the sentences?)

As an interpreter, one has to know, as it were, every word of the story – not just who are the main characters (or in musical terms, themes), but also the contrasts and similarities between them, how they develop and inter-react, and what journeys they experience. Reminding oneself of all this, and listening to the new messages that great music will send us each time one comes back to it, takes time. It’s not enough just to understand the basic structure (although that is of course essential; if you hear a performance that seems to go on forever, it is generally because the interpreters have no idea of the overall shape of the music, and are groping their way through the poor piece – it happens too often, unfortunately).

I find that the music of Bach, Beethoven and other works of true complexity (as well as, usually – and paradoxically – true simplicity) take far longer to reintroduce to my fingers and mind than, say, Shostakovich’s first concerto, which I was also playing on this same trip. I would certainly not call the latter superficial in any way – it’s a masterpiece! It is certainly not lacking in complexity, either. It is wonderfully cinematic and comparatively clear-cut, though, each note representing something pretty definite; returning to it is like a reunion with an old, very familiar friend. I have always to re-examine the score, of course – there are still surprises in store, details I have missed.

But I don’t think that my view of the essential nature of the concerto is likely to change radically. The last Beethoven sonatas, on the other hand, demand constant basic searching and revision, an open mind about the profound secrets concealed beneath the surface; there is more information per note, in fact, than in the Shostakovich. That is why I, in common with every other musician, have to keep practising the Beethoven sonatas so hard every time – both at my own instrument and away from it. And if I were to tell myself that by all those hours of work I have fully probed the depths of the music – I would be deluding myself!

(c) Steven Isserlis/Slipped Disc

Big Pharma does some good.

The Indianapolis Orchestra woke up this morning $10m the richer.

It plans to spend the money on streaming concerts and improving the musicians’ pensions. The orch is on a bit of a roll with a good, young conductor, Krzysztof Urbanski, and 15 percent growth in ticket sales.

INDIANAPOLIS – The Lilly Endowment Inc. announced today that it was awarding the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra a grant of $10 million as part of a special initiative to strengthen the financial stability of Indiana arts and cultural institutions. The grant, one of the largest gifts in the ISO’s 85-year history, will help support strategic objectives which are designed to sustain and improve the ISO’s financial future.

“These organizations have a long history of providing enlightening and educational experiences to the Indianapolis community and to the people of Indiana,” said Ace Yakey, the Endowment’s vice president for community development. “Their creative and energizing programs, exhibits, concerts and strong audience and community engagement have a significant economic impact on the city and around the state and on their national and international reputation.

“Indiana marks its bicentennial in 2016 and Indianapolis celebrates its bicentennial in 2021. The Endowment hopes that these grants enable recipients to cross these milestones in a stronger position to sustain and build on their contributions to the cultural vitality of the city and state.”

The ISO intends to use the grant to support an investment in technology to enable audio and video streaming of select ISO performances at Hilbert Circle Theatre, to fund its defined benefit pension plan for ISO musicians, and to support its endowment.

“Lilly Endowment’s support comes at a critical point in time for the ISO,” said Vince Caponi, the Chair of the Board of Directors of the ISO. “This transformational grant will enable the ISO expand its reach beyond the walls of our concert hall, will help fulfill an important commitment to our extraordinary musicians, and will help secure the future of the institution. I hope others in the community will continue to recognize the importance of this cultural asset and provide support for our ongoing operations.”

“Throughout the years, the Endowment has supported the ISO at crucial moments in our history,” said Gary Ginstling, the ISO’s Chief Executive Officer. “The ISO Board, Musicians and Staff are overwhelmed at the generosity of this extraordinary grant and the confidence it shows in our strategic direction and our ambitious plans.”

The Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra has seen strong attendance growth in recent seasons, with a 15 percent growth in overall sales to Hilbert Circle Theatre concerts from FY14 to FY15. Student ticket sales have increased dramatically as well, with an increase of 50 percent over the past two years. In addition, the ISO has continued its tradition of innovation with its new Lunch Break Series of casual 45-minute performances each summer, and its new 317 Series which brings the Orchestra outside its concert hall and into central Indiana communities. The ISO will announce its FY15 financial results at its Annual Meeting on December 7.

The elusive pianist will play at the reopening of Teatro Petrarca at Arezzo, where musical notation began.

The concert will be given on the 20th anniversary of the death of Arturo Benedetti Michaelangeli.

John Ferrell has died, at 90.

Before settling in Tucson in 1974, he toured with the fabulous Stradivari Quartet.

This is a rehearsal shot from Parsifal at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, where Nadja Michael is dressed as a veiled, implicitly oppressed Moslem woman on her first Act 1 entrance.

True to Wagner? True to Islam? Or just a misplaced fashion statement?

The director is Marcelo Lombardero.

Several maestros have now made the point on Slipped Disc and elsewhere that audiences ought to be allowed to express their reactions in between movements of a musical work.

Among them are Esa-Pekka Salonen, Leonard Slatkin, Mark Elder and Daniel Barenboim.

It may be time to abolish the mid-movement taboo- with certain qualifications.

Our friend Tim Page has been reminded of a piece he wrote almost 30 years ago in the New York Times, imploring concert audiences not to erupt too soon. We reprint it below with his permission, and one emboldened phrase.

EARLIER this season, I sat with a rapt audience at Carnegie Hall, listening to Mahler’s Symphony No. 9. Written during the composer’s final illness, the symphony provides one of the most difficult, haunting yet ultimately rewarding musical experiences in the repertory. When the final notes of the closing Adagio dissipate into air, the silence should be as eloquent as the sounds have been – a charged residue, if you like; a silence that is a musical statement in itself, transfigured by what has gone before. At Carnegie, Mahler’s silence, so hard won, lasted barely a second. Somebody shouted ”Bravo!,” the audience responded reflexively, and one left the hall frustrated, rudely shaken from an engrossing dream.

Premature applause is one of the most disturbing elements of our musical life. I have long despaired of hearing the final notes of the first act of ”Der Rosenkavalier” in an opera house. It is a wonderfully poignant moment, and it is inevitably interrupted. The Marschallin sits at her mirror, worrying about her lover, feeling mortal. The curtain slowly starts to fall, and the exquisite cadence Strauss created to accompany its drop is suddenly lost in applause. Ironically, the better the performance has been, the more quickly it is likely to be disrupted.

Will I ever attend a performance of Schubert’s ”Trout” Quintet in which the playful false ending in the last movement isn’t broken by ill-timed cheering? The fans vie to shriek the first ”Brava!” at diva concerts, and a recent performance of Debussy’s ”Clair de Lune,” was marred by clapping the moment the final note was played – the musical equivalent of a photo finish.

Music is not a sporting event but, at its best, a taste of the sublime; the most abstract of the arts, it is, paradoxically, the most human. Jean Sibelius asked that his Symphony No. 4 be followed by no applause whatsoever, and that the audience leave in thoughtful dignity. Glenn Gould once titled an article ”Let’s Ban Applause!” Most of us would not go this far, but applause can be ruinous unless it is carefully considered.

Applause between movements or sections of a song cycle is bad enough (I recently attended a rendition of Schumann’s ”Frauenliebe und Leben” in which every single song was bravoed, handily sapping the score’s collective power), although a polite note in the program guide or a shake of the head from the artist will usually discourage such transgressions. But what can one spectator do to still premature applause without seeming to shush, hector and hamper one’s neighbors, who have, after all, paid for their tickets and are legitimately entitled to express their pleasure?

A plea: hold the applause until the music has completely died away. Wait for that relaxation of a conductor’s shoulders, the drop of a pianist’s hands or the easy grin that releases singer from song cycle. And then applaud as long and loudly as you wish. Your enthusiasm will then complement the music, rather than diminish it.

(c) Tim Page, May 1986