How Zubin Mehta and a marimba ensemble helped solve Mozart's 'murder'

mainThe award-winning crime writer Matt Rees is about to publish a new thriller, Mozart’s Last Aria. He explains its musical origins in an exclusive article for Slipped Disc.

Writing The Music Behind Mozart’s Last Aria

By Matt Rees

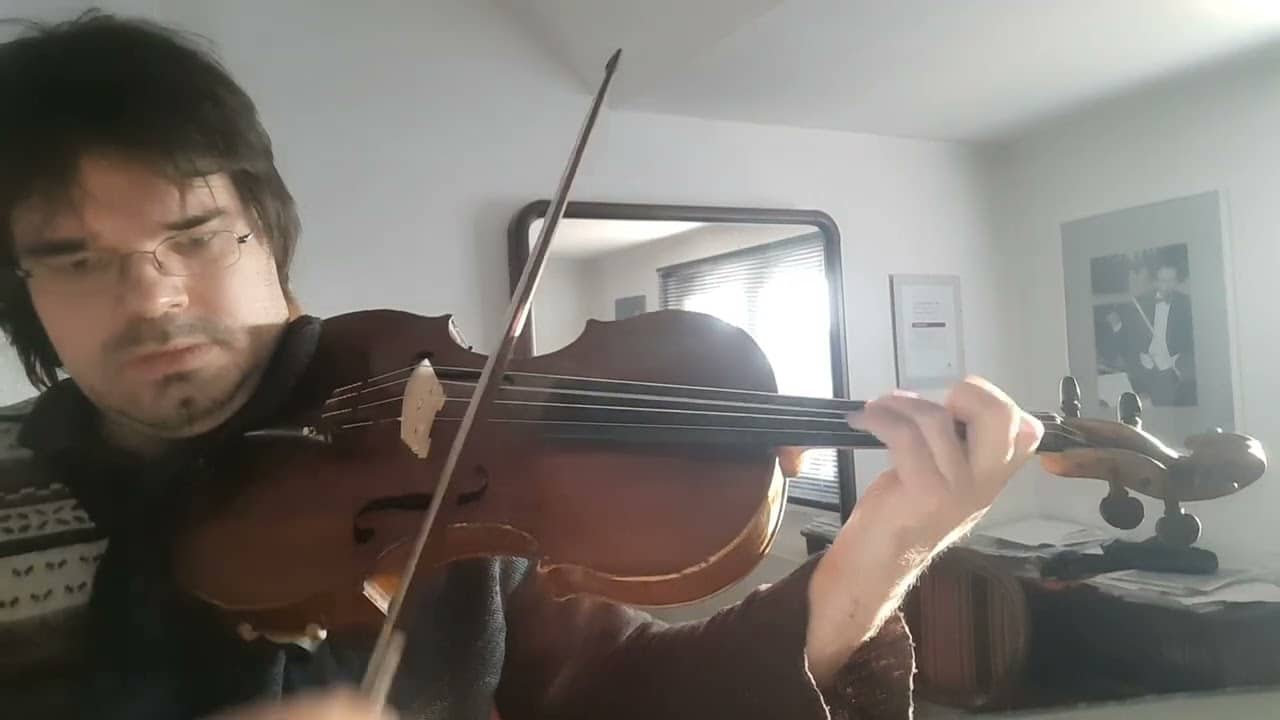

I’ve played music all my life, but I’m no musician. After my initial childhood lessons I parted ways with the classics. No more etudes by Heller for me. I’ve been a guitarist and bassist in various rock ensembles in New York and elsewhere. Less sexily, I played glockenspiel in my high school band.

A few years ago, I was at a small dinner in Tel Aviv with Zubin Mehta after one of his performances with the Israel Philharmonic. I happened to ask him which composer he considered most indispensible. “I’d find it very hard to live without Mozart,” he told me.

Maestro Mehta’s comment started me thinking. What had it been like for Wolfgang’s contemporaries to lose him? As I cooked up my book idea, I knew that though I would draw on new historical research into the period and Mozart’s life his music would be at the centre of the mystery. I’d have to write convincingly about its structure. Its performance. And the intellect behind it.

That made me look anew at Mozart’s music. I learnt to play piano, which gave me a way to see inside Wolfgang’s music. It made me think more deeply about theory than my experience as a rock guitarist. (Surely THAT doesn’t surprise anyone, but it was worth demonstrating anyhow.)

Among many helpful musicians, my main guide in this was my dear friend Orit Wolf, a fabulous Israeli concert pianist who has taught at the Royal College of Music. (You can see her dressed up as Nannerl to play Mozart’s Fantasia in D on this video trailer for the book.

The Fantasia was incomplete on Mozart’s death, but it’s even more freighted with intimations of doom than the Requiem). Our discussion of Wolfgang’s piano sonata in A-minor gave me the idea of building the entire novel around the mood of that piece, so that the novel should seem somehow musical even when the characters aren’t making music.

The A-minor sonata was written when Wolfgang was in Paris, mourning his mother who died while chaperoning him on tour, so it’s as much about death as is my crime novel. Its opening Allegro maestoso is disturbing, discordant. I thought of this as the introductory theme of my novel, in which the calm world around Nannerl collapses with news of her brother’s death.

The thoughtful second movement (Andante cantabile con espressione) is the book’s central section in which Nannerl explores the Vienna Wolfgang left behind. Then comes the final Presto, in which the disturbing themes of the first movement are resolved, just as Nannerl uncovers the truth over the last chapters of the book.

Orit also introduced me to some of the techniques great musicians use when they prepare for a performance. For example, she told me that when she first looks at a piece for a performance she decides what colour the music makes her think of. Before each performance, she visualizes that colour and it creates a mood in her. In turn that mood is reflected in the music as she plays it.

So I did the same thing. Before I wrote about Nannerl Mozart performing a piece of music, I listened to it for a long time. I’d hold a colour and a season in my head as I wrote.

Finally, I overcame the po-facedness of my childhood piano teacher –– to make the book entertaining as well as historically accurate. I was aided in this by a performance of The Magic Flute a few years ago in London. It was done by a group of singers from a South African township and scored for marimbas, of all things. I’m sure Wolfgang would’ve loved it.

(c) Matt Rees/Slipped Disc

Comments