The final reckoning

mainThe sackings have started at Decca. Out of 32 staff at the London headquarters, just six are being retained.

That is one to manage the office, one to answer the phone and open the mail, two to look after the royalty accounts and two more to deal with whatever instructions come down from corporate headquarters.

One thing is clear: there is nobody left at Decca to make records.

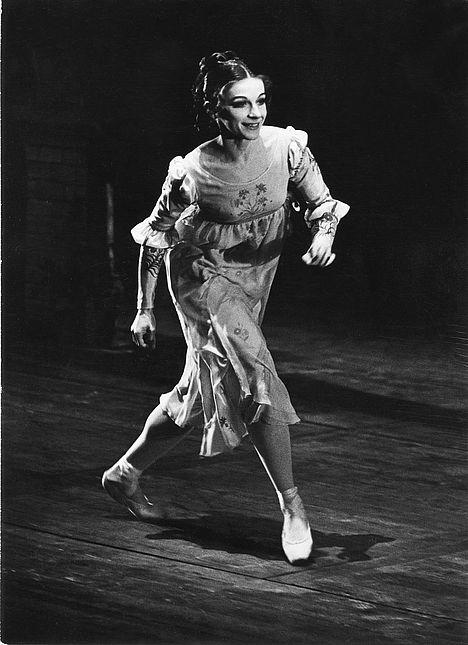

Classical artists, including the now-celebrated Tutula Bartley, are being transferred to Universal Classics and Jazz (UCJ), a crossover business that produces such half-baked trivia as the boy band Blake and the East London lad who gave up his junior football career to play the saxophone. Cecilia will feel in good company.

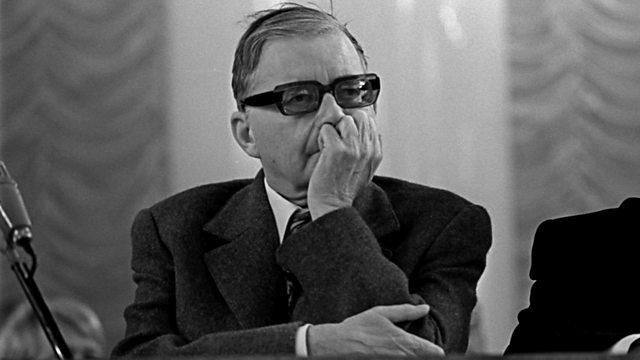

The residual staff at Decca will report to Michael Lang, head of Deutsche Grammophon in Hamburg.

The notion that Decca will continue to function as a production centre after these abolitionary measures is a mixture of wishful thinking and corporate fiction. The author of the fantasy is Christopher Roberts, head of UCJ.

Roberts once tried to persuade me that corporate ciphers like himself earn huge salaries and bonuses in order to protect madcap artists from their wild whims and maximise the revenue potential from their works. Given that Roberts has dedicated so much of his energy to eliminating outlets for classical artists, I wonder if should perhaps think of revising his job description – so long as he still has a job.

Decca is dead. A grand tradition has been laid waste. What remains is history – and a golden opportunity to reinvent the spirit of enterprise in classical music.

Newbies and start-ups, post your plans and logos in the comment space below.

LATE EXTRA: A sharp-eyed reader directs me to a news release from Universal Music Group, the monster that killed Decca. UMG has just appointed three more vice-presidents, just what the music world most needs right now, to ‘erase lines between physical and digital’.

One of the new bonus-guzzlers is called Rotter, Mitch Rotter. You couldn’t make it up.

Long live EMI – the only decent major record company issuing new recordings, and mining its catalogue. EMI, it’s the real British Recording Company. So sad about Decca.

Even though I agree with the overall thesis, and that the death of Decca is only a symptom of an industry that ate itself from within, I think that you fail to see a wider issue with the recording industry as a whole.

The mainstream recording industry (e.g. Universal/D.G./Decca) has totally missed the boat with digital technologies and instead of realizing that listeners (I wont denigrate them by calling them consumers) will use these technologies to their advantage and have instead waged war against these technologies (e.g. Pirate Bay) and the people who they rely on turn a profit.

Once the newpapers saw the internet as the enemy, we now have editors blogging away merrily. Fancy that!

You may well mourn the loss of the ‘grand tradition’ of the big recording studio. As you correctly point out, musicians and engineers can produce the same result in any venue with equipment that will fit on a hand-trolley and be mastered on a conventional desktop computer. I will go one further and suggest that the days of recording music for the purposes of selling on a piece of plastic will go to the same way.

Classical music is a minor battle in the context of this war.

This is not entirely a sad event. For the musicians and listeners it presents a world of opportunities. I just hope the corporate hangers-on can wake up and smell the coffee.

NL to David Hardie: I can’t speak for the rest of the media but I have been urging print/internet interaction since 1996 and wrote my first newspaper online strategy paper in 2001. I don’t think the corporate hangers-on will get it until it’s too late. By that time, most newspapers and record labels will be history.

I must therefore be in the minority -growing minority since there seems to be a business of manufacturing and selling them- who enjoys sound quality and musical interpretation to the point of being interested in 45RPM vinyl in both classical and jazz.

The only reason I would buy a MP3 track from a classical release is to satisfy my curiosity cheaply, mostly to compare with a piece that my favorite artist has released or performed.

Clearly it is the degradation of sound that has turned me away from CDs and this is a question of production and medium. This is a human factor and many “tonmeisters” are indeed tone “schuler”!

David has it spot on; all major record labels (and many others), across genres, were late to the digital party. Record label executives failed to look ahead, and decided that “this digital thing” needed to be stopped as it appeared to be interfering with their business. The tremendous growth in online sales over the last few years shows just how wrong they were, and gives us an idea of just how much better off they would all be if they had got on the bandwagon a few years earlier.

When David notes that they saw the internet as an enemy upon which to wage war he is absolutely right; and waging war against your customers never helps one’s bottom line. Music, in the early days, was only pirated because there was a lack of legitimate services to acquire music from. Record companies attempting to introduce DRM (Digital Restrictions Managament!) failed (notably Sony trying it by the back door with illicitly installed software on users computers), and most proponents of DRM – even currently – fail to recognise that **DRM only harms legitimate users** ! Anyone pirating music isn’t caught by DRM at all, a situation made all the more obvious in the movie market – buy a DVD and you can’t take it on holiday and play it in the USA becasue of the daft region encoding scheme. Pirate the film, though, and you can watch it anywhere.

Of course, there are artistic concerns too, but a basic failure to understand a new business model and to monetise the online opportunity early enough has lost record labels millions of dollars (quite literally millions in the UK alone if you look at the value of downloaded music). These $ would go a long way in the current climate, and could quite possibly have helped underwrite some of the necessary artistic change for future survival.

There are those of us who have been championing digital music from early on, and calling for an end to DRM. With iTunes ditching DRM, I hope we are nearer to a sensible solution for digital music. For some labels, though, it is four years too late, and they have only themselves to blame.

AVI