Why Piatigorsky moved to Hollywood

mainFrom our moderator, Anthea Kreston:

The Fortnightly Music Book Club continues this week with another look into the marvelous life of cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. Questions by readers are answered below by our guest host, Evan Drachman, a Curtis-trained cellist and grandson to Piatigorsky.

Through passionate and informed reader comments, we have expanded the conversation. Keep an eye out for the final installment in two weeks – a word from cellist Nathaniel Rosen, and a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the new movie „The Cellist“, premiered in Montreal. We will hear from Terry King about the premier, as well as voices behind the camera. We have been in touch with the Piatigorsky Archives in Los Angeles over 19,000 documents and they have provided some great photos. Finally, here is a link to a fascinating and spicy interview of the late John Martin, the principal cellist of the National Symphony Orchestra.

Our sources are “Grischa” by M. Bartley, The Cellist, Piatigorsky’s out of print autobiography but available for free here – and Terry King’s book „The Life and Career of the Virtuoso Cellist“ (available on kindle). Readers are encouraged to comment below, or submit question based on any of these books, as we will be looking at Piatigorsky for one more installment. Please continue to submit questions via email to: Fortnightlymusicbookclub@

Thank you, Evan, for your insightful responses to reader questions.

Question:

In chapter 17 of The Cellist, Piatigorsky details his experiences with stage fright, interspersing funny personal anecdotes with visceral descriptions of his own struggle to perform under duress. What tools do you think he used to manage his stress?

Answer:

It is probably impossible to know what goes on in the mind of another human being when they are dealing with performance anxiety. They can describe the worries they are having. They can describe the physical manifestations of the stress. They can talk about the tools that they use to overcome these obstacles. We as outsiders can witness behavioral changes leading up to and during performances. We can assess the success of the performance and make a guess as to whether the playing was the same, better or worse than it might have been without the stress of a public concert.

I cannot speak for my grandfather. I know only the things he has written, said and done to deal with concert nerves. I think that there is no doubt that he suffered from considerable anxiety. Once in an interview I heard him say that he believes that there doesn’t exist a musician who is truly a conceited character…(he then laughed)…ESPECIALLY BEFORE THE CONCERT! (Joking he pretended to be that character.) “Now I will play and it will be HEAVEN!” (more laughing).

What did Piatigorsky do to deal with the nerves? I imagine that he did what we all do – he told himself that he is a fine musician and cellist. He told himself that the audience is friendly and wants for him to succeed. He told himself that he knows the music inside and out and will not falter. Whatever he did worked well enough to allow him to perform thousands of times. Those people lucky enough to have attended his concerts say that he was larger than life on the stage. His recordings, although magnificent, pale in comparison to his live performances. He struck a heroic figure carrying his cello above his head as he strode onto the stage. Perhaps the nerves even served to heighten his abilities as a performer.

One of Piatigorsky’s students told me that he discussed with them the level of comfort one can achieve while sitting at the cello. (I am not sure if he meant simply playing the instrument or actually performing.) He said that if one desires comfort they should lie on the beach. Playing the cello is many things, but it is definitely not comfortable!

Question:

Piatigorsky has a wide range of performance experiences, from playing in brothels to concertos with the Berlin Philharmonic. In The Cellist, he seems to relate equally to all of these opportunities – mixing happiness and dissatisfaction equally to all opportunities. What kind of message does this broad range of performance experience send to musicians? What should we take away from this?

Answer:

My grandfather was hyper-critical of himself. He would only remember the things that went wrong in a concert. On one tour he had a string of bad reviews. He mailed all of the negative clippings home to my grandmother. She didn’t have much faith in music critics. She knew her husbands’ playing and didn’t read any of those reviews. As a special surprise she brought them to a shop and had them bound beautifully in leather. What a surprise when he returned home!

On another occasion, Piatigorsky was to perform as soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra. At that time, the family was living in Philadelphia. My mother (a young girl) heard at school that all of her teachers and friend’s parents were attending the concert. After the concert my grandfather had only negative things to say about his performance. He felt it had gone terribly badly. My mother did not want to go to school. How could she face her teachers and friends? Of course she couldn’t admit why she didn’t want to go to school. When she arrived at school it was to wild acclaim. The concert had been magnificent!

My grandfather performed in every possible situation a musician can encounter. He cared deeply about the music and strove to play his cello to the best of his abilities always. I don’t think that he played any differently for the Tuesday Morning Music Club than he did as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Piatigorsky often said that he was a servant of Art. His duty was to the music. He said that if he lived a thousand years he might know half of what there is to know. “No matter how one strives to reach it, the music remains above.”

Question:

In 1949, Piatigorsky moved from the East Coast to Los Angeles. How do you think this move affected his career and personal life?;

Answer:

Piatigorsky moved his family to Los Angeles because his son’s doctor said that a drier climate would help his ear infections. Anyway…that is the story I always heard. In fact, Hollywood was the happening place to be in the United States. The movies were becoming the height of American culture. Not only were the movie stars moving to LA, but many of the musicians. Heifetz, Rubenstein, Rachmaninoff, Hindemith…Los Angeles became the epicenter for classical music in America. I don’t think that his career would have been any different if he had stayed on the east coast.

Piatigorsky loved Los Angeles. He loved rooting for the Lakers, walking in the garden behind his house and feeling the sand between his toes on the beach. Most of all he adored teaching his very talented students at USC. The west coast climate suited him perfectly. I can imagine him dressed with his usual elegance, striding in his garden. I don’t believe he ever considered moving.

Question:

Piatigorsky was associated with three legendary piano trios in his life – first with Flesch and Schnabel, then with Milstein and Horowitz, and finally in the “Million Dollar Trio” with Heifetz and Rubenstein. How did chamber music enhance his extraordinary solo career?

Answer:

Piatigorsky was a truly sociable human being. He loved to be around people. Playing chamber music, teaching, playing bridge or telling stories and drinking into the wee hours of the night after a concert, he thrived on human interaction. You can feel the connection that he has in his chamber music recordings. He is not trying to outshine the other artists. He is tremendously happy making music together with his colleagues and friends.

Piatigorsky needed his solo career to succeed in his profession. He also had an enormous amount to say on the cello. That amount of expressiveness could not be contained in a chamber music setting. I know from personal experience that performing as a soloist with an orchestra or as the featured artist on a recital is a test of one’s abilities. After a successful concert it is as though one has “gone through the flames”. I would imagine that there was something of that for Piatigorsky.

New Year’s Eve was an important holiday for my grandfather. There would always be a big party and there would always be chamber music. For years in Los Angeles it would be with Heifetz and all of their colleagues and students. Later, the party migrated to my parent’s house in Baltimore. I remember as a child hearing Leon Fleisher, Berl Senofsky, Walter Trampler, Stephen Kates, Nathaniel Rosen, Jeffrey Solow, Doris Stevenson…the list goes on. I think that for my grandfather, chamber music was perhaps the most fun he had in music.From the moderator:On a final note, I am trying to find a copy of Sascha Schneider‘s memoir. My husband found a large stack of unbound pages many years ago on a shelf at a university, and to his surprise, it was the unpublished memoirs of Schneider. He said he stayed up all night reading – it was a fascinating read. Does anyone know anything about this? I want to read it!

See you in a Fortnight!

You write: “I am trying to find a copy of Sascha Schneider‘s memoir. My husband found a large stack of unbound pages many years ago on a shelf at a university, and to his surprise, it was the unpublished memoirs of Schneider. He said he stayed up all night reading – it was a fascinating read. Does anyone know anything about this? I want to read it!”

This was “published” in 1988 with the title “Sasha: A Musician’s Life.” The back of the title page reads: “Design and production by Stanley Drate, Folio Graphics Co. Inc., New York.” It was probably self-published, as there isn’t a publisher’s imprint on the title page. It is 299 pp, with many illustrations. The book is paperbound, with plain light brown covers. I have seen two copies, each inscribed by Schneider, one to Felix Galimir, the other to Joan Peters.

Looking at WorldCat, there are not many libraries in the US listed with a copy. They are: Juilliard, Smithsonian, Boston Univ., Harvard, Univ. of Texas (Harry Ransom), Western Washington Univ., New York Univ., SUNY Albany, YIVO Inst. Jewish Res.

So it won’t be easy to find. The only copy I see for sale online is $850.

Malcom – great information. Maybe I can try to get an interlibrary loan somehow. Maybe we could work on a reprint…..

Malcom – any way you feel like trying to get one from a library for me – I don’t have a US address anymore. Where do you live? I will be in Philadelphia soon – is that close to you? Just if you are up for an adventure…..

If you are willing to wait you can probably obtain it through interlibrary loan but you will probably have to read it at you local public or academic library

Evan attended Curtis? That begs only one question: what happened?

You write: “Piatigorsky was associated with three legendary piano trios in his life – first with Flesch and Schnabel, then with Milstein and Horowitz, and finally in the “Million Dollar Trio” with Heifetz and Rubenstein.”

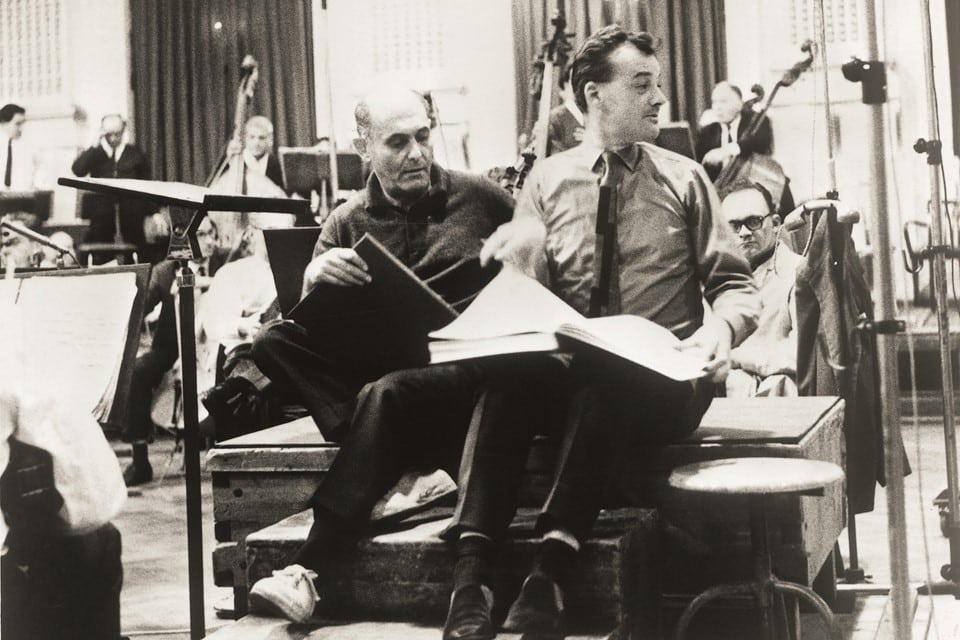

There is a well-known photograph by the famous photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt of Milstein, Horowitz, and Piatigorsky in their tuxedos–Milstein (left) and Horowitz (center), and Piatigorsky (right), each holding a cigarette–with some flowers in the background.

It is widely assumed this was taken at a concert performance by the three as a trio.

In fact the only known concert performance of the three as a trio took place March 30, 1932, in Carnegie Hall, as a benefit for Musicians Emergency Aid. The program for this one and only concert as a trio is illustrated in Terry King’s biography on p. 77. They also never recorded as a trio.

So was the Eisenstaedt photo taken on the occasion of that Carnegie Hall concert? No. We know the photo was taken in the early 1930s in Germany–Eisenstaedt did not leave Germany and come to the US until 1935–and there is no known performance in Germany of the three as a trio.

If anyone knows the occasion at which the Eisenstaedt photo of Milstein, Horowitz, Piatigorsky was taken, now is the time to speak up.

It is said that the three performed in private settings as a trio. But actual details of such private trio “performances” are hard to pin down.

In his autobiography–From Russia to the West, the Musical Memoirs and Reminiscences of Nathan Milstein”–Milstein talks (to Solomon Volkov) about the Carnegie Hall trio concert (pp. 182-183 and 185): “As I’ve said, Piatigorsky, Horowitz, and I met frequently, but we didn’t perform together. I don’t know how the idea came up–that we had to perform for the public as a trio. It must have been one of Merovitch’s tricks [Merovitch was the manager of all three in their early days]. The concert was set for March 1932 at Carnegie Hall. We selected Beethoven’s B-flat Major Trio and Brahms’s C Major Trio. We also wanted to play a Russian work. But Tchaikovsky’s trio seemed too long and we didn’t dare make cuts in it. So we settled on Rachmaninoff’s trio. The composition has its divine moments, but it also has its longueurs. Rachmaninoff himself came to our rescue, cutting about twenty minutes of music. He was delighted that his trio would be on the same programme with Beethoven and Brahms, and he attended our rehearsals regularly. (There is a picture of our trio rehearsing, but for some reason Rachmaninoff was not photographed with us). Listening to the Brahms at the rehearsals, Rachmaninoff would exclaim ‘I don’t like Brahms! Too bad!’ and then would try of explain. ‘Brahms knew how to compose.’ This was not meant as great praise…. Piatigorsky always liked appearing in ensembles, and he very much wanted to continue to perform in a trio with Horowitz and me. In Chicago one time, all three ‘musketeers’ had had great success appearing separately, and the local patrons insisted that we perform as a trio there, too. Piatigorsky grew excited. ‘It will be sensational!’ I disagreed. ‘Girsha, it’ll be not so good, believe me.’ Horowitz sided with me”

Hello Malcolm,

The photo was taken just before their Carnegie Hall benefit concert for musicians relief.

Terry

As logical as Terry’s suggestion is, it cannot be correct.

Why?

We know who took the photo: Alfred Eisenstaedt. We know he was German and did not come to the US until 1935. So how could he have taken a photo at Carnegie Hall in 1932? He could not have done so.

Eisenstaedt is a very well known photographer and this photograph of his is well known. The location of the photo is always attributed to the Berlin Philharmonie, with the date of either 1931 or 1932 given. I am not saying that information is correct, although it probably is. But I am saying an attribution to Carnegie Hall 1932, which no one in the world of photography has ever proposed, cannot be correct.

But if it was at the Berlin Philharmonie, what was the occasion?

This is not the place to rehearse ideas I have had about the photograph. So far I have not been able to substantiate any with documentation.

Eisenstaedt’s photos were published in magazines. After coming to the US he became a famous photographer for Life magazine, where so many of his well known photos were originally published.

One of those photos many readers of Slipped Disc will know, but they do not know the photographer was Eisenstaedt. It is the photo in Life magazine–p. 27 of the issue of August 27, 1945–of the celebration in Times Square, New York, on “V-J day” marking the end of World War II for the US, with a sailor kissing a nurse. The caption of that photo reads: “In the middle of New York’s Times Square a white-clad girl clutches her purse and skirt as an uninhibited sailor plants his lips squarely on hers.”

That was the same Alfred Eisenstaedt who took the photograph of Milstein, Horowitz, Piatigorsky. I mention it here only because, just as the V-J day photo appeared in Life magazine, the Milstein, Horowitz, Piatigorsky photograph probably appeared in a German magazine in the early 1930s. But I do not know which magazine. If someone does, then the question of the location and circumstances of this photograph might be answered.

Another interesting, rare biography of a Russian émigré musician is Duet With Nicky, by Alice Berezowsky, which can be found in used bookstores here and there. It is a well-written tale of an interesting life ranging from the Imperial Chapel Choir and Rasputin to mid-century Manhattan.

I imagine that Los Angeles was also fairly inexpensive at the time, probably much less so than Manhattan, as it was not nearly so developed as later in the 20th century.

Reminds me of the early seventies Neil Diamond song. Even then one could stil say of LA “Palm trees grow and rents are low…