Our diarist Anthea Kreston has been talking to a guy who should know.

I am home for a quick turn-around between four days of recording in Bremen and the continuation of our tour (next stop Budapest). Sleeping in the same bed in Bremen for four nights felt like luxury, as did the acoustics of the Sendesaal Bremen (constructed in 1952 for the purposes of radio recording – with a floating floor and ceiling suspended by large metal coils), not to mention the company of pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja and Tonmeister Christoph Franke.

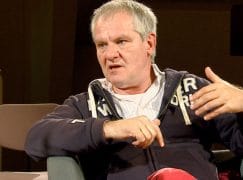

I got to know Christoph better and he agreed to have a walking interview with me during a break from one of our long sessions. He is the Creative Producer for the Digital Concert Hall of the Berlin Philharmonic (as well as producer of their CD’s). He has collaborated with artists from Jonas Kaufmann to Lang Lang, on such labels as Deutsche Grammophon, EMI, Sony and Warner. And, he is a super down-to-earth guy (and dad to our favorite babysitter).

Anthea: What is your philosophy of recording – what are you looking for?

Christoph: At the end, I am looking for something which is different from a concert, because a concert can’t be recreated on a recording. A recording has to be, in an ideal world, the closest the musicians can get to their utopian idea of what a musical work should be like, and sound like, if you conserve it for eternity. And so you use all the possibilities you have in a recording setting to repeat things, make them better and better until you find the ideal you have, and to polish everything until you forget about all of these boring details like intonation and ensemble, you simply forget about them when you listen to the recording.

A: So you are saying it is music without boundaries, in some way?

C: Yes, yes….

A: Is it possible to achieve flow – musical and otherwise – in a recording? I felt like we did.

C: In my experience, definitely. Of course many people say it isn’t possible – you destroy the musical flow if you edit things into each other, but first of all, that is one of the challenges of good editing, that you only edit things together which have a musical flow.

A: Working with you, it felt like we had a working group flow, and in the past, when I have recorded….with all of the stops and starts – this time it felt like all of us – in studio, whether playing or working from the other side – like we were going together

C: Yes – absolutely – that is necessary for a good recording – that you are not limited by outside obstacles like time, distractions, outside thoughts. If you have a situation where all of you can really dive into the music and all you want is to make a great recording, no matter how long it takes, or how many times you repeat, or how long you discuss, or how long it takes to find the best sound (on the microphones or the instruments), if all of that is a common idea, then you can create something.

A: That’s great. What are the specific skills that you, personally, need to do this job?

C: (Chuckle)…. First of all, I have to enjoy working with technical equipment and be so fluent in the use of technical equipment that I forget about the difficulties of using them, that it is just a tool, which then makes it possible to completely concentrate on creating music and trying to understand what the musicians want to achieve and help them to make it possible, to realize it.

A: So your equipment is an instrument – like our instruments are an extension of our bodies?

C: Yes, sort-of – I mean, the microphones and recording devices, in the end, in my opinion, it’s not so important – in the end, it is about creating and producing a musical piece together, the way you interact, how you put it together in the end.

A: How much is you, and how much is us? You are kind of dancing around this idea – like ‘it’s them’, but you are also saying ‘it’s me’. What’s the percentage? All six of us, equally – maybe, or – how much of it is you? Does it feel like the right amount of you? Do you ever feel like it isn’t enough of you?

C: Oh, it’s always enough of me! It is 100 percent the musical idea of the musicians, and if I am interfering or interacting or asking questions, then it’s in order to get some hidden idea out, which wasn’t conscious by the musicians, or to make the idea more obvious. But I realized very soon that my dream wouldn’t be to be a musician, simply because I am not a musician…

A: But you are a musician in there, you are!

C: Yes, but it’s different to be – I don’t want to say passive – but I am not the one creating the musical idea.

A: But I do feel guidance from you, though, I do feel like it’s absolutely – the things you were bringing up – you could hear that either someone had an idea which they had not fully inhabited, or perhaps there was a moment when the question hadn’t been answered, so that is very important.

C: Yes, but that is still different from creating something from nothing.

A: Aha. How much of your job is psychological? (Chuckling) It probably depends on the group or the person?

C: Well, there is a lot of psychology, not that I ever consciously learned how to do that. When you are studying, every student says “We need to learn about psychology – it would be so great to have a course” but it simply doesn’t exist.

A: That’s too bad.

C: Yes. It is too bad, but the other hand, it’s also something which is difficult to be taught, and also difficult to learn. I don’t know. I also don’t consciously think about it – I maybe have some kind of subconscious strategy, I know when to be sensitive and I know when to encourage (because I think I’m a relatively positive person, (Laughter)). I think it’s so important when you are creating music to have a positive spirit, and I have attended recording sessions where, you know, (laughing, awkward faces)

A: Yes – I have as well!! (lots of laughing)

C: ‘Ugh, that was wrong, and we have to do that AGAIN…this kind of thing…’

Of course that is completely against the whole idea, we are trying to create something exciting and fascinating, and also you can only create a piece of art if you are encouraged and positive.

A: I agree. The nature of recording, even more so than for performing, has such a slippery slope into negativity, for yourself, and for others, and frustration, this is such a huge, real danger which is always on the cusp. You know what I am saying – it can ruin everything. And so, with your guidance, we have remained extremely positive, but those couple of moments, when we started to take a turn towards the dark, (more laughing), I noticed that you stood back, and you didn’t interfere, and you let us wiggle our way out. I thought that was very interesting. Has there ever been a moment before in your life, where you felt like you had to step in and help? When it became too dark?

C: There have been situations where you have the feeling that this is really going to turn into a crisis, and you have to decide if it is a crisis which is necessary, and has to be gone through, and the next day it will be better. And usually the crisis comes on the third day of the recording (more laughing, nods of agreement). That’s very normal. But it also depends on the whole setup of people, whether you think they need it – is it something which needs to be discussed, and even if it turns into something dark but you think it will fine in the end. Or, is it not for the purpose of a good result, and I need to interfere and just steer us back into the track. But, especially with the Artemis, I know that strong discussions are just in the DNA of the quartet, you know (nodding, agreements). And I have experienced much stronger discussions that what we had here in these sessions.

A: So – you thought it was all pretty cool.

C: Yes – It was all very easy!

A: Good. This is your 4th Artemis recording? Right? I think you did one with Natasha (late Schuberts), with Vinny you did the Mendelssohn and Brahms (both of which won an Echo).

C: And the unpublished Dvorak.

A: Right – 5 recordings.

C: The last one with Friedemann. We were to do Smetana as well. That Dvorak remains unedited.

A: I see. I have a follow-up on something we touched on earlier. I know you played cello and piano – what kind of theory and aural skills do you think are necessary for you? I find that you have a very synthesized, complete package – both in construction of the pieces and aurally. Did you augment these yourself?

C: That is what I studied. That is one of the few courses in the world where you can study exactly that. The old traditional Tonmeister course – which was actually put together by Schoenberg. Many years after emigrating to the United States, In 1946 (just 6 years before the Sendesaal was built) he wrote to the Chancellor of the University if Chicago, asking to develop a degree so that the soundmen (that is what he called them) can learn about music as well as sound production. Schoenberg, being quite a modern man, he realized that making a recording requires both the technical and musical side. Someone who was fluent in both – so he suggested to set up a course like that, and then this idea came quickly to Germany in 48 or 49, there was a man called Thienhaus, and he set up a Tonmeister program at the Hochschule für Musik Detmold.

A: So this was based on Schoenberg’s model – it had been developed in the States, but not completely?

C: I am not certain about the specific connections between these moments and people, but when I first researched, I found the earliest mention to be about Schoenberg. Then someone from Detmold (who came from Berlin – Hans-Ludwig Feldgen) took the idea from Detmold to Berlin, and set up a Tonemeister Degree at the Universitait der Künste in the 50’s (which is where the Artemis holds their Professorships). And that is exactly that combination of technical subjects – you learn mathematics, physics, acoustics, electronics, but you are based at the music department, and you learn all the subjects that a conductor would learn, except the conducting part. Counterpoint, piano, and your main instrument, aural skills, music theory.

A: Fantastic. How did you come to this career?

C: When I was 10, I must credit my mother – she realized that was interested in technical things, and she gave me an electronics kit, and I built my first radio, and all that, and I was completely obsessed with these things, putting things together, had building them, routing a loudspeaker into the living room, connecting it into speakers to the children’s room, and listening to the conversations in the living room and things like that. And at the same time I started to learn piano, and so for all my life it ran parallel. I was a very early computer adopter (something like ‘78), and at the same time still playing the piano and cello. It was always great to have this possibility of, for some weeks or months, to put the focus more on the musical side, practicing like crazy, and then doing some technical project where I did something completely new and advanced.

A: Tell me about your work with the Berlin Philharmonic. I loved seeing you there when I was subbing with them – you seemed to be everywhere – running from corner to corner of the big hall, speaking to Simon Rattle, hunched in intense conversations in the cafe.

C: Well, I could call myself one of the think-staff – an inspirator for the Digital Concert Hall. As early as 2005-06, together with Robert Zimmerman, the Managing Director of the Berlin Phil Media, we had this idea that we, somehow, could get the orchestra into the next millennium. And since then, I took part in the team setting up the Digital Concert Hall for them. And again – this is a mixture of the technical side – really fiddling around with the internet and hard drives and really hands-on stuff, but at the same time, dealing with the musical side, interacting with Simon Rattle, making sure the musical quality we out in the archive and transmit – that this is good enough, setting up our own label, interacting with the all of the artists, and thinking about the repertoire and all of that. And so it is a dream, somehow. It is one of the very few successful streaming projects for classical music.