Death of the first Indian composer to receive an Arts Council grant

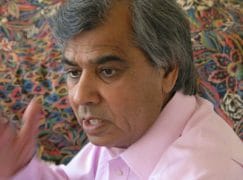

mainAlberto Portugheis laments the death of his friend, Naresh Sohal, in an obituary exclusive to Slipped Disc. Naresh, who died earlier this month of a heart attack, was 78.

Naresh Sohal was born on 18 September 1939 in Punjab, northern India. There was a strong folk music tradition in the region, but there were no musicians in his family. Naresh’s father, however, besides being a civil servant, was a renowned Urdu poet and the boy developed an ear for the spoken word through serving tea at poets’ gatherings. From an early age, Naresh showed an interest in popular music.

By the time he reached college where he was enrolled for a degree in Mathematics and Physics he had acquired a harmonica, and became a versatile performer of rock and roll and Indian film songs. He learned all works by ear. With a select band of friends he entertained his fellow students at social gatherings. He also wrote works for the Punjab Armed Police band.

Keen to push forward the frontiers of his musical knowledge, the young Sohal determined there and then to abandon his degree course. After a few weeks in Bombay, where he was lured by the film industry, Naresh heard Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ Symphony on the radio. It was his first experience of European classical music, and it had a profound effect. In 1962 he left India for the U.K. intending to find a way of learning to write western music.

Sohal first job was as a copyist with Boosey and Hawkes, the music publishers. In the evenings he attended various educational institutes to learn western music theory and began writing his own work. One day, at Boosey’s, Naresh heard Eonta, a new work by the Greek composer, Xenakis. The experience made him discover that music can be determined by ideas that derive from mathematical calculation and not just by pretty melodies with harmonies attached to them. He encountered the composer and teacher Jeremy Dale-Roberts, who took him on as a private pupil.

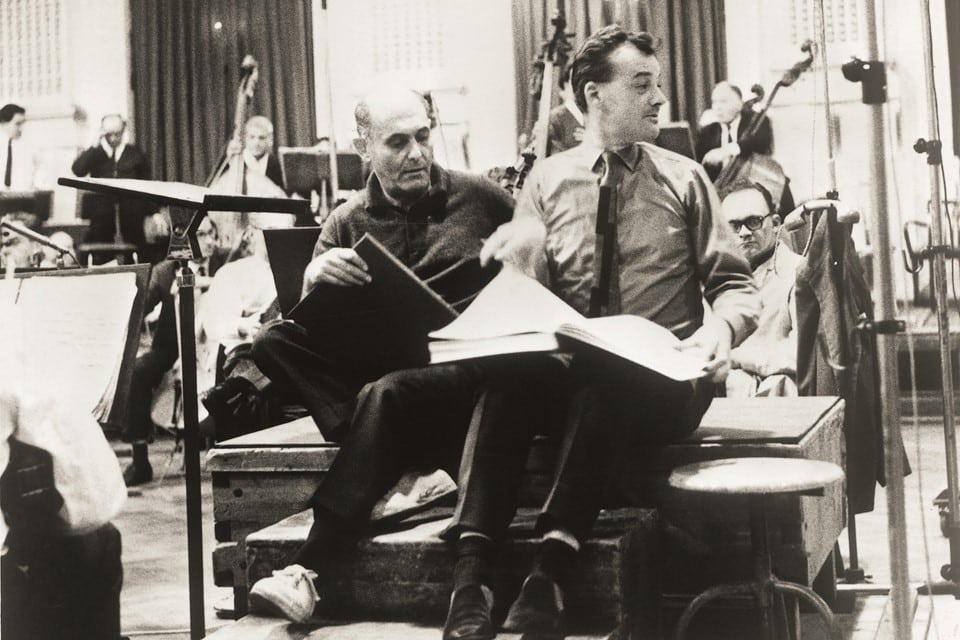

After leaving Boosey’s to work as a free-lance copyist, Sohal had more time to spend on his own composition. In 1965, he completed his first orchestral score, Asht Prahar, a tone poem based on the Indian concept of the eight periods of the day. Immediately after came Surya (1965) for chorus, percussion and solo flute. The text is in Sanskrit and is taken from the Rig Veda. Sohal had to wait until 1970 to hear what he had written. In 1969, the Society for the Promotion of New Music selected Asht Prahar for a public performance in rehearsal at the Royal Festival Hall where it was played by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Norman del Mar. The work was very well received and from then onwards , Naresh enjoyed years of production and international success.

In 1970 the SPNM commissioned Kavita 1, for soprano and eight instruments. In the same year Sohal composed the orchestral piece Aalaykhyam 1. In 1971, the BBC broadcast a performance of Suryagiven by the Ambrosian Singers and Andrew Davis conducted the first performance of Aalaykhyam 1.

In 1972, Sohal won an Arts Council bursary which enabled him to move to Leeds University to begin a study of the compositional aspects of micro-intervals. This was a thesis which he was ideally placed to produce, given his familiarity with Indian classical music where the octave has twenty-two divisions, and the fact that he often tantalised performers and audiences by using micro-intervals in his own work. However, the lure of the act of composition was once again too great and the study was left unfinished. At Leeds, Sohal met his partner-to-be, Janet Swinney, who was busy abridging Dickens’ Dombey and Son for radio. They shared a consuming interest in Indian philosophy.

Sohal returned to his London base, where he was now caught up in a whirl of activity: Aalaykhyam II, completed in 1972 was performed that same year by the English Chamber orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis; Kavita III, composed for soprano Jane Manning and Barry Guy, double bass, was taken on an Arts Council tour and Asht Prahar was recorded by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis. Sohal won the 1974 Young Composers’ Forum with the chamber piece Hexad, and in 1975 the talented late Hungarian ‘cellist Thomas Igloi, conducted by David Atherton, gave the first performance of Dhyan 1 (1974), with the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Kavita II was one of the BBC’s entries for the 1975 International Rostrum of Composers held in Paris. It was chosen as one of the best ten entries and subsequently broadcast on twenty radio stations throughout Europe. And so it went on, with Sohal’s music heard internationally, performed by many distinguished international soloists, chamber ensemples, orchestras and conductors. In 1982, Naresh Sohal’s Wanderer, for baritone, orchestra and chorus, was premiered at the BBC Promenade Concerts, conducted by Andrew Davis.

In 1983, Sohal and his partner moved to Edinburgh. This brought a change of pace and a widening of focus. In the concert hall, the composer continued to work on a large scale. In 1984, he turned once again to the elegiac works of Tagore for From Gitanjali, a work for baritone and orchestra commissioned by the Philharmonic Symphony of New York. The work was premiered in New York, in the composer’s presence, by John Cheek and the New York Symphony Orchestra, conductor Zubin Mehta. Sohal followed this with an orchestral work, Tandava Nritya (1984) commissioned by the British Council for the London Symphony Orchestra for a planned tour of India. This tour did not materialise, but Tandava Nritya was eventually premiered in 1993 in the Royal National Scottish Orchestra’s rehearsal hall in Glasgow. Earlier, in 1986, Sohal’s violin Concerto for the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra was premiered with the Chinese violinist Xue Wei as the soloist and conductor Martin Brabbins.

In 1987, Sohal was the first non-resident Indian to receive the Padma Shri, the Order of the Lotus, by the Government of India for his services to Western Music. During this period he at last had the opportunity to produce works which involved dance or drama as well as music. In 1987, commissioned by BBC Television, he completed Gautama Buddha, the music for a ballet about the life of Lord Buddha, based on his own scenario and choreographed by Christopher Bruce. This extremely ambitious work was premiered in Houston, Texas, where it was given seven performances by the Houston Ballet. It then transferred to Edinburgh where it formed part of the 1989 International Festival programme.

That same year, on Sohal’s fiftieth birthday, the Paragon Ensemble performed in Glasgow Madness Lit by Lightning, a music theatre piece which is a contemporary fable about human degradation. Also to mark the composer’s fiftieth birthday, ‘cellist Anup Kumar Biswas, a long-time champion of his work, commissioned a work for his trio, the Guadagnini. At the same time, Sohal began writing for film and T.V. In 1993, Naresh Sohal and his partner returned to London. In 1996, the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins gave the first performance of Lila, a major orchestral work which it had taken Sohal five years to realise. This is a musical representation of the process of enlightenment as described in Hindu philosophy and experienced through meditation.

In 1997, the piece Satyagraha, commissioned to mark the fiftieth year of Indian independence was performed at the Barbican by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Zubin Mehta. In 1998, Sohal completed a second music theatre piece in collaboration with Trevor Preston. This is Maya, an allegory drawn from Indian mythology. He moved on to complete a song cycle, Songs of Desire, a setting of three poems by Tagore. This work has been performed variously in Bombay, London and at the Dartington Festival. He also produced Hymn of Creation, a major work for chorus and orchestra. This is a setting of the seven mantras on creation from the Rig Veda. A period of experimentation followed. Sohal broke new ground with Songs of the Five Rivers, settings in the original language of poems by classical Punjabi poets Bullay Shah and Waris Shah. This work was commissioned by the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and given its first performance by them with soprano Sally Silver.

Sohal experimented with the use of Indian drums and tabla in chamber and orchestral contexts. One of these was a concerto for viola and orchestra, commissioned by the Russian Chamber Orchestra of London and premiered by them in 2002 with soloist Rivka Golani. More recent works have included Three Songs from Gitanjali commissioned by the Spitalfields Festival and a commission from the Israel Philharmonic to celebrate the 70th birthday of maestro Zubin Mehta. This large piece, called The Divine Song, for narrator and orchestra based on text at the heart of the Bhagavad Gita, was performed in 2010 in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, with narrator Itay Tiran and the baton of Zubin Mehta. The work was a great success and a year later was played twice by the Staatskapelle, Berlin with again Zubin Mehta conducting and Stefan Kurt, narrator.

Around the same time Sohal met the famous Chinese harmonica virtuoso, Jia-yi He, for who he wrote Reflection, for harmonica and piano. Which Jia-yi performed in Singapore and Taiwan. At Jia-yi’s request, Sohal made another version of the work, for strings, piano and harmonica. Sohal’s Shades VIII for solo harmonica, dedicated to Jia-yi, was performed in New York and Hangzou, China. His last big piece was a commission by the BBC for the 2013 Proms. The Cosmic Dance is based on the Big Bang theory and Creation mantras from Rig Veda. It was performed by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and conducted by Peter Oundjian.

Sohal was a mould-breaker who transcends national boundaries. He has given us some of the most inspiring, most rewarding and most important works of our time. The day Naresh left us was the day of Buddha Purnima in Nepal and India. ‘Informally called Buddha’s birthday, it actually commemorates the birth, enlightenment (nirvana) and death (parinirvana) of Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) in the Theravada tradition.’ Those who are familiar with Naresh’s work, will know that it consisted almost entirely of an exploration of matters spiritual and philosophical. Those of you who knew him personally will know that he was an avid and dedicated practitioner of meditation.’

On a personal note, I would like to say how privileged I am to have been a friend of Naresh Sohal, whom I have always called, since premiering his “Mirage” for piano at the Fairfield Halls in Croydon, “the Schubert of our time”. For his spirituality and for his love of nature, poetry and life.

His ‘Cosmic Dance’ as played at the proms in 2013:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pY4gA1rINVU

… and a harmonica piece:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phANwi5TaTk

“One day, at Boosey’s, Naresh heard Eonta, a new work by the Greek composer, Xenakis. The experience made him discover that music can be determined by ideas that derive from mathematical calculation and not just by pretty melodies with harmonies attached to them.”

Interestingly, in this piece there is no ‘influence’ of Xenakis-like modernism to be detected. It seems that musicians from eastern countries which have severely suffered from WW II or comparable upheavels, like Japan and S-Korea, have been more susceptible to a new music which cuts all roots with a tradition: doing away with ‘the past’ as a territory infected with disaster and beginning from scratch. But India has a long and high-minded musical tradition itself.

“………….. that music can be determined by ideas that derive from mathematical calculation and not just by pretty melodies with harmonies attached to them.”

As interesting, this was the general attitude within ‘new music circles’ in the sixties and seventies – and still much later and even surviving in our days – which seems to imply that the entire premodern repertoire is made-up of ‘pretty melodies with harmonies attached to them’, a most naive description of Western classical music as if produced by an extra-terrestial alien, or modernist composer, in short: someone entirely ignorant of the art form.

That may be so, John, but some mention must be made of Sohal’s qualities at the crease as batsman and first-rate leg-spinner!

I am so sorry to lose a close friend, a great composer Naresh Sohal, we were talking about play his harmonica concerto just 9 days before his death. It is my great honor that he has written two harmonica works for me. May his soul rest in peace.