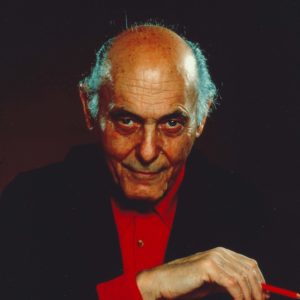

“You know the nicest thing about Georg?” a woman friend had said. “He cannot believe the success he has achieved.” “That’s quite true,” agreed Solti, “although I know how hard I worked for it. Harder than anybody.”

He started out in Budapest, the son of an unsuccessful businessman and a strong-willed mother who made sure there was enough money for piano lessons when little György – he became Georg on the German opera circuit – turned out to have perfect pitch. He gave his first piano recital at 12 and was quickly admitted to the Franz Liszt Academy, supplementing the syllabus with six weeks of private lessons from Bela Bartók. At the premiere of his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, Solti turned pages for the great composer.

Had he stuck with the piano, he could have made a decent career. But Solti was determined to conduct, an unattainable dream in Admiral Horthy’s crypto-fascist Hungary. “It was out of the question that a Jew, which I am, should get any sort of state job – and all the orchestras and opera companies were owned by the state,” was Solti’s blunt recollection.

Retracing his steps for autobiographical research, Solti had a whole village turn out to welcome him to his father’s birthplace, planting a tree in his honour and aggravating a deep-seated ambivalence. “It was a strange, moving occasion,” he said. “It brought me back to my Hungarian origins – because I strictly refused to have anything to do with them for years. I was chucked out twice, and that was enough.”

In October 1932, aged 20, Solti went to Germany to work as an assistant to the conductor Josef Krips in Karlsruhe. Hardly had he found lodgings than a Nazi violinist tipped off the Volkische Beobachter, which launched a poisonous attack on Krips for engaging an “eastern Jew”.

Back in Budapest, he scratched around for piano dates and worked as a repetiteur, rehearsing singers at the Opera. The conductor, Joseph Rosenstock, said he had never seen anyone “so talented, or so shy”.

Finally, in 1937, he took a letter of introduction to the president of the Salzburg Festival, Baron Puthon, craving permission to observe at rehearsals. As luck would have it, he arrived during a flu epidemic. “Do you know The Magic Flute?” said the Baron. That afternoon, he was playing the rehearsal piano for the cast when Arturo Toscanini, the most fearsome conductor of all time, entered the room. “My heart stopped. I froze. With one finger, he gave me a tiny beat. I followed. After a while he said one word: ‘Bene.’ ”

I heard Solti recount this story on his return to Salzburg 52 years later, breaking off a family holiday in Italy to stand in for the dead Karajan, a power-playing ex-Nazi who had placed every possible obstacle in his path. Remarkably, there was neither triumphalism nor bitterness in Solti’s voice, only a sense of wonderment.

He next saw Toscanini in Switzerland in the summer of 1939, hoping to accompany him to America. Unable to get a visa, Solti received a cable from his mother telling him to stay put. Hitler had invaded Poland and Hungary was unsafe. During the war, his father died of natural causes; other relatives were murdered in the Holocaust.

Trapped in a neutral state, without friends or a work permit, he was taken in by a tenor, Max Hirzel, in exchange for being taught the role of Tristan. In 1942, fearing repatriation, Solti chanced his hand at an international piano competition.

“You know how hard it was for me?” he demanded. “I have no visual memory. Unlike Karajan and others who can turn a page and fix it in their minds, I have to learn bar by bar, and tone by tone.

“I had what pianists call a finger memory, but, in the excitement of the Geneva competition, I lost it. We were four finalists and I was playing last. I arrived half an hour early and sat at the piano to warm up. I played the fugue from the middle of Beethoven’s opus 110 sonata, a very simple motif, and suddenly I didn’t know where to go. So – panic, sheer terrible panic.

“I went out, wanted to go to the office to say I’m not playing, I’m sick. But nobody was there. I came down just as the other pianist finished. The usher said, ‘It’s your turn – go.’ I have no idea how the hell I got through it. I won first prize, but it was terrible. I was a wreck. Since then, I have learned music note by note.”

The prize earned him enough money to live on for five months and official permission to teach five pupils “not one more”. Swiss neighbours reported him to the police for practising too loudly – “Why couldn’t they ask me first to be quiet?” he wondered.

When the war ended, Solti was 32 and no nearer to his podium ambition. He got in touch with a Hungarian exile, Edward Kilenyi, who was in charge of music in the US occupation zone of Germany, and offered to head the opera in Munich.

Rejected on sight, he went to Stuttgart and conducted Beethoven’s Fidelio, signing a contract as music director virtually the next morning. However, hearing that Munich was having second thoughts, he slipped out of town and went for the main chance, abrogating his contract and earning the enmity of the Stuttgart mayor, a future president of the Federal Republic. Most maestros cover up such moral lapses in their august memoirs, but Solti did not mind exposing the indecency of his haste.

Having only ever conducted two operas – Figaro in Budapest and the Stuttgart Fidelio – he found himself in charge of a company hallowed by the two Richards, Wagner and Strauss. “It was not for several years that Munich began to discover I was conducting everything for the first time,” he said.

He spent six years in Munich – “they chucked me out; the minister wanted a German, non-Jewish conductor” – and nine in Frankfurt, where the administrator eventually said to him: “Solti, you must go now; you are too good for us.” He was almost 50 before he hit the world stage, flying out to the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra – only to fly straight back after a challenge to his artistic authority. He arrived in London in 1961 as music director at Covent Garden. The rest is unalloyed glory.

Over the next decade, he raised the Royal Opera House to rank with the world leaders – Vienna, La Scala, Paris and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Under Solti, London saw big stars and epochal productions – the Callas-Gobbi Tosca, the first Moses und Aron, the most memorable of Arabellas. He taught Britain how to run a top-flight opera house and helped British-trained singers break into Europe. Dames Gwyneth Jones, Margaret Price and Kiri te Kanawa are all shoots from the Solti nursery.

In 1969, he took up the baton at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and held sway for a quarter of a century, burnishing a big-band sound that raised a brash ensemble from the Midwest into world contention with Karajan’s all-conquering Berliners. The Chicago-Solti combination sold five million records. In all, Solti made about 300 recordings, including the major symphonic cycles and the first recorded Ring. No living maestro comes close. In America, where titles matter, he was pronounced the World’s Best Conductor.

Yet, perhaps due to the frustrations of his delayed start, Solti pushed for more. His podium style, always ungainly, was likened by one US critic to shadow-boxing. In quieter passages, where other conductors put on a dreamy look, he fidgeted and fretted. “Why do you conduct all the time with both hands?” Richard Strauss once asked him.

Some of his performances seemed driven to the point of pain. In rehearsal, his rages were apocalyptic. At Covent Garden, they called him “the Screaming Skull”; in Chicago, he was accused of replacing strong-willed players with sycophants.

Musicians in the London Philharmonic Orchestra, which he directed from 1979 to 1983, referred to him in a volume of interviews as “poison”, “greedy” and – this from the LPO’s vice-chairman, Nicholas Busch – “the worst conductor ever”. The oldest member of the orchestra looked forward to dancing on his grave. Not one player in the whole book had a good word for him – yet Solti stepped in time and again to save the orchestra’s season when a music director fell sick or a management disintegrated.

Everywhere he conducted there are musicians he helped in distress – with a quiet chat, a glowing reference or a personal cheque. He was an absolute pushover for hard-luck cases and refugee causes. When the Chinese opened fire at Tiananmen Square, Solti called off a Chicago tour and donated the proceeds of a London Messiah concert to stranded dissidents. “I became a refugee in August 1939,” he told them. “I know what it is to be cut off from my home.”

Close friends found him warm, considerate and charming. Women found him irresistible. We were chatting about one of his Frankfurt friends, the Marxist dialectician Theodor Adorno, when Solti reflected that they shared a love of wine, women and good music – “in reverse order”.

“Much the same as you do,” I ventured.

“Not wine,” corrected Solti, whose evening tipple was a malt whisky.

“But women?”

“Always.”

He recalled the sweet beginnings. “Until I came to Switzerland, I was very faithful. I had one girlfriend and I wanted to marry that girl. If I didn’t have such an intelligent mother, who said, ‘Just wait another year – you have no money’, who knows what might have been?”

The loneliness of exile drove him to seek more varied company. His head was turned in the street by passing blondes, and very often he found them responsive. Later on, at Covent Garden, it was rumoured that Solti gave white mink coats to the singers he slept with.

Counter-rumour had it that some singers bought themselves white minks to give an impression of intimacy with the music director. Who knows what to believe? In his memoirs, Solti has preserved a gentlemanly discretion.

“I have been as truthful as possible in the book,” he said. “Listen, what’s wrong with liking women? Vat you want – I should be homosexual? It’s the natural way. A musician loves life. I love life in all directions.”

But the act of love was never far from his mind. At a recent record industry party, he recalled being lobbied by an American executive who was defending three-minute shellacs against Decca’s long-playing record. Solti heard the man out, then said: “Tell me, what do you prefer – coitus interruptus, or coitus? Myself, I like coitus.”

He married for the first time in Switzerland – a girl called Hedi Oechsli who was pregnant with her second child when they met, and left both husband and children for the penniless musician.

Solti made no bones about the illicitness of their liaison. Nor did he make much of the fact that her husband was a member of parliament who could have had him expelled. Solti credited Hedi with getting him to read books and polishing his table manners. In London, she did much to smooth his path with the Covent Garden toffery.

He met his second wife, Valerie Pitts, when she went to interview him one Friday night at the Savoy for BBC Television, and stayed. She was married and, at 27, barely half his age. “It was a violent affair,” he once said. Valerie opened his eyes to the visual arts and gave him a family, for which he would sacrifice anything – racing out of Chicago concerts to reach London in time for his little girl’s birthday.

He lay awake worrying what could be done to bring young people back to classical music. He planned to collar Tony Blair and urge him to increase Covent Garden’s subsidy in exchange for cheaper seats. “Otherwise, better to close it down than to carry on muddling,” he believed.

He made repeated attempts to push through a merger between two London orchestras and create a world-class ensemble. “It is a great sadness that we can’t play a better operatic or symphonic standard here,” he lamented. “The musicians deserve better and the public deserve better.”

Latterly, I would watch him stand back in the podium and allow himself to enjoy the music. “He is extremely demanding and egotistical,” said a close associate before Solti’s death, “but, at heart, he is a very humble person.”

In Chicago, he prayed for his successor, Daniel Barenboim, to do well, “because then I can be forgotten”. Asked how he would like to be remembered, Solti shrugged and seemed, for the first time in my experience, lost for words.

As I moved towards the door, he made a parting request. “Would you kindly,” said Solti, “not bring out so much my love of ladies?” He shot me another of those male-to-male looks. “Anyway,” he added, quite unconvincingly, “I am an old man now.”

(c) Norman Lebrecht, 1997