Lisa Ji Eun Kim of the Houston Symphony Orchestra has passed the audition to join the Boston Symphony.

A Juilliard grad, Lisa is originally from San Diego.

She starts in Boston in September.

Lisa Ji Eun Kim of the Houston Symphony Orchestra has passed the audition to join the Boston Symphony.

A Juilliard grad, Lisa is originally from San Diego.

She starts in Boston in September.

The outgoing music director of the New York Philharmonic is asked for his views on the President of the United States. His reply is translated on screen in German subtitles.

Watch.

Antonino Fogliani, 40, has been named principal guest conductor at Deutsche Oper am Rhein.

He starts in September.

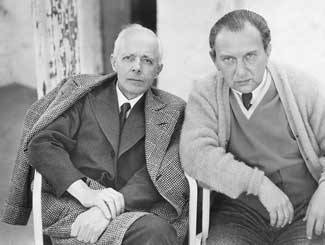

The death has been communicated of Bernard Millant, owner of one of the most respected Paris ateliers for stringed instruments and, especially, bows. Players pay up to $14,000 at auction for one of his bows.

He co-wrote the definitive book on French bows, L’Archet (2000).

Bernard was 87. Rue de Rome will never seem the same.

Gianandrea Noseda announced last night that he plans to record the 15 Shostakovich symphonies for the LSO Live label over the next few seasons.

This is an intriguing prospect on several counts. Noseda spent 10 years as resident conductor at the Mariinsky Theatre and is fluent in Russian language and culture.

His take on the complete Shostakovich will come up against evolving cycles from Vasily Petrenko in Liverpool (on Naxos) and Andris Nelsons in Boston (on DG). There’s a prospect of really fruitful contrasts.

photo: Teatro Reggio, Torino

Noseda is incoming music director at the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and principal guest with the LSO.

The baritone Igor Golovatenko has told a Russian website that he has twice been refused a visa at the British consulate for this summer’s Glyndebourne Festival.

Golovatenko, who took Glyndebourne by storm in a Donizetti role in 2015, is due to sing Germont in La Traviata. Rehearsals start on April 14.

Someone needs to phone Theresa May. Fast.

UPDATE: Now the Philharmonia loses soloist due to UK visa issues.

photo (c) Tristram Kenton/Glyndebourne

Mahler’s seventh symphony at the Barbican last night marked the retirement concert of Patrick Harrild, principal tuba for 29 years and a notable voice on the orchestra’s board. He was also the principal exponent of the rather lovely Vaughan Williams tuba concerto.

Patrick went out last night with the most serene opening-movement solo.

The right-hand back wall won’t look the same without him.

A vote of no confidence by musicians in the Halle state orchestra has apparently led the city to terminate the contract of general music director Josep Caballé-Domenech after a single term. He will leave in the middle of next year.

The musicians’ decision took the city council by surprise. They avoided naming it as a cause for the conductor’s dismissal.

Josep Caballé-Domenech, 44, is also music director of the Colorado Springs Philharmonic and an international guest conductor . Some musicians felt he spent too much time commuting.

First report here.

photo: Rolex

Our diarist Anthea Kreston on returning to the third Bartók string quartet:

What it feels like to play Bartok

Playing in a quartet is challenging in several ways. Technically and intellectually you must be at the top of your game. It is like a debate team – every musical argument will be picked apart and you must have rock-solid back-up of your points. Emotionally it is a roller-coaster – saving and expending energy alternate constantly (nap on the plane, focus like crazy from 5-10:30 pm), and constant self- and other- criticism is a dangerous tightrope. Life/work balance is erratic and can’t be fully controlled. And, entering a quartet which has been celebrated continuously for over 25 years, there are expectations from critics, colleagues, and audience which are so demanding, the only way I cope is by completely shutting off that part of my brain.

When I was a member of the Avalon Quartet, I was a kid – age 21-28. When we played Bartok, the expectations were – how can I say it – curious and supportive. But now I am on stage with three people who have performed this particular piece perhaps between 50 and 100 times already. And play for an audience who had grown up with those piece and has, most likely, heard every major string quartet live in concert.

I have to step into my position like a fine-tuned machine, with unshakeable confidence and leadership both technically and emotionally. As a second violinist, my role is many-fold. I must be the “wing-man” for my first violinist – her perfect foil and supporter. When she has the melody (around 80% of the time), I must follow her and at the same time lead the lower voices. I must provide completely solid and reliable intonation, which has a different function and rule every single note. I must step into the role of melodic leader, playing a melody octaves lower, in a bad register, farther away from the audience, and must do it immediately and clearly. And I must learn the language of this quartet – new ideas and techniques from the ground up (from vibratos, bow technique, a new intonation philosophy, and different structural priorities). And not let anyone see me sweat or have floppy over-age-40 upper arms.

So – now I will provide what it feels like for me to play the third Bartok String Quartet, with all of these expectations on the table.

Back stage, I take some deep breaths, say good luck and see you later to the quartet (it does feel like we take a trip once we step out into the stage – and return to reality after we return backstage after each piece). Often, when I first walk onto stage, I have a feeling of extreme cold which washes over my body, and I feel light-headed. This clears up a bit when I contact my colleagues, and also I scan the audience and take it all in. I tend to talk to myself silently through the Bartok – I need the encouragement and the warnings of dangers to come.

The first 4 notes of Bartok 3 are a tone cluster shared by the three lower instruments. These four tones are each a half step from one another, and the opening, haunting and lilting first violin melody contains all of the other 8 notes, to complete the 12 tones in an octave. The problem with these first 4 notes is that they are technically unreliable. The first can be set – a solid note from the cello. The second, however, is also played by the cello, in a slur, and is a harmonic. This poses 3 problems – how to make the bow sound the same with a separate vs. slurred articulation, and how to make a solid note and double stop harmonic sound the same, and to speak in a clean rhythm. Depending on what happens, the third tone, played by the viola, responds to the tempo and articulation of the cello, and I have just a split second to respond. Then, I breath. I say to myself – “you’ve got this – the rest of the 1st page you can totally do”. As I work my way through that first page, my pulse lowers, my focus calms and i steel myself for the next section.

As I reach to turn the page, I say “ok now – keep it together and focus, you can do it”. There are 2 hard passages in this next page – one for counting and one for group matching. My pulse rises, I feel my cheeks heating up, but I know I have a calming moment before I have to lock it down and work my way through the mine-field of the second section.

Pages 3,4 and 5 are for me, the most demanding. Any slight mis-step by any member sends an immediate shockwave through the ensemble. The rhythm must fit seamlessly, and we all must be ready to adjust. It also awakens in me an animal instinct. It is like I can turn into an actual animal – fight/flight or a lion on the hunt. Total focus, total control, total animal instinct. The other week, my animal instinct took over to such an intense degree, I felt like I was in a sound tunnel. I could only hear my blood coursing through my ears – everyone seemed far away, and I could feel my heart – like there was someone actually thumping on my chest with all their might. I was in total control, but later I realized that this was dangerous – I couldn’t completely let my animal out again. I pulled myself back from the brink, looking ahead to the 2 pages before the coda, where the quartet has a time to step back, to contemplate and weave together long slow melodies. I spent the first of these two pages just getting myself back to human, and was able to flow and engage through the second of these slow pages.

But – I can see the final page turn – it is already deeply creased, and darkened by the many times I have grabbed it to turn quickly, but quietly. The coda. Oh my god.

“Ok, you can do this. You can do this. Just two more pages”. My eyes focus, and it seems like I am looking through a telescope at my music. This is extremely fast, the rhythmic dialogue is constantly changing, and there is no moment to regroup. I slow down time – I stretch out every measure like it is made of silly putty, and I feel like my hearing is so clear, so in focus – like I have 4 sets of Bose headphones on, one for each of us. Here too, the animal takes over, which I think it should, but not like an animal on the hunt, but an animal hunted. Every step can be a trap, every move on my periphery could have the tip of an arrow pointed at me, a red mark of a rifle sight on my chest. I have to dodge and attack, and finally, for final last line, we hold hands, all together, for a devastating final blow.

When the audience begins to clap, I sometimes feel like someone has dumped a bucket of cold water on me, or I feel like crying, I am so overwhelmed – in every way. We don’t look at one another until we reach back stage. I hear sighs, see rings of sweat marks on the floor around each of our areas as we return to the stage, finally able to smile and become human once more.

Musikverein today.

Photo: Dieter Nagl

l-r: Christian Thielemann, Prince Charles, Vienna Phil chairman Andreas Großbauer, Thomas Angyan, concertmaster Rainer Honeck.

Captions, please?

Looking back on 18 successful years as executive director of the San Francisco Symphony, Brent Assink tells SF Classical Voice of one notable omission. He confesses that:

‘We don’t have the resources or the energy, or whatever it is, to slot ourselves into a logical relationship with the African-American community, a relationship built on the kind of cultural tradition we have in other communities. If you don’t have that connection, the effort feels forced; it feels artificial, and then, I think, you’re worse off than if you didn’t do anything at all.’

Discuss.

Full interview here.

Dallas Opera is staging a reunion for participants in its increasingly influential course for women conductors.

The following conductors will be travelling to San Francisco next week, to take part in the 2017 Hart Institute Reunion:

Some of the others are already far too busy.