How do musicians’ brains process so many notes?

mainThat’s the subject of a paper presented by Eriko Aiba, of the University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo, at the 172nd Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America this weekend in Hawaii.

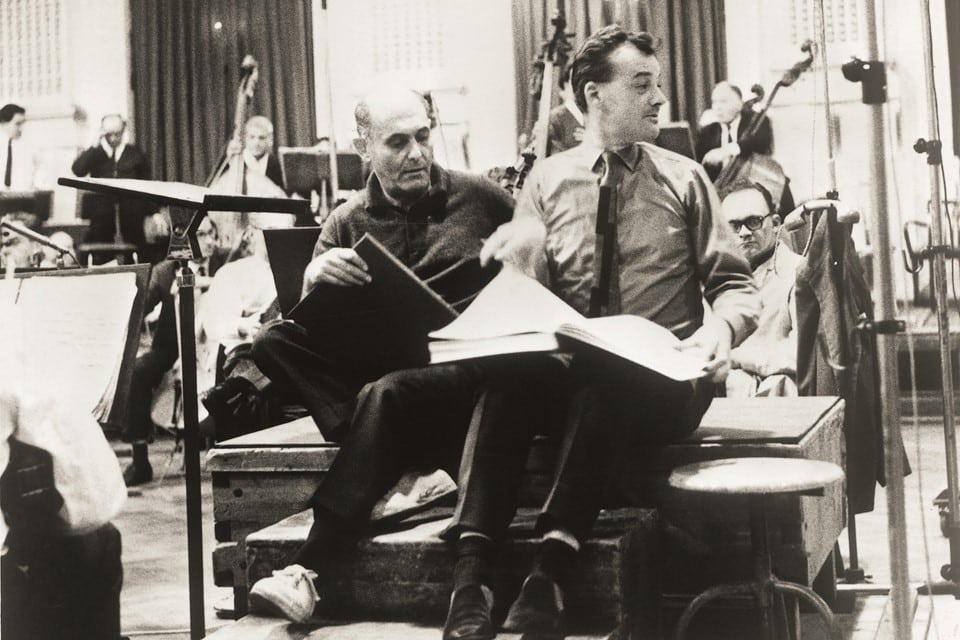

Aiba (pictured) began learning to play the piano when she was five years old, and quickly realized that musicians might be roughly divided into two groups: sight readers and those who play by ear.

“When considering a human brain as a computer, playing a musical instrument requires the brain to process a huge amount and variety of information in parallel,” explained Aiba. “For example, pianists need to read a score, plan the music, search for the keys to be played while planning the motions of their fingers and feet, and control their fingers and feet. They must also adjust the sound intensity and usage of the sustaining pedal according to the output sound.”

Such information processing is too complicated for a computer, so how do the brains of professional musicians handle such complex information processing?

Read more here.

I like that phrase “…search for the keys to be played.”

I don’t know many pianists that embrace the “hunt and peck” method of playing, but hope the question is asked the next time someone interviews Murray Perahia or similar:

“…and finally, something I’m sure many of us have wondered… There are SO many keys on a piano: how do you find which ones you need to play?”

‘Learning styles’ we’re all the rage a few years back in the classroom with audits on new pupils to find out if they were kinaesthetic (touchy-feely), auditory or visual learners so there’s nothing new really about all of this. I believe that this learning audit trail never really did anything beneficial aside from identifying the trait, another classroom gimmick which didn’t contribute anything but wasting the teachers’ time and giving a pupil an excuse.

Nevertheless, putting my sceptic hat on one side, there might be something in it. Why can some children sight read well (a minority in my experience) and some memorise well? Or is it really, as I suspect, all down to some old-fashioned hard work?

I count myself as a pretty nifty sight-reader but memorising stuff is harder.

Then again, if I had a more frequent and systematic practise routine I’ve no doubt that my memory would improve.

I remember reading in a book called something like “Interviews With Great Pianists.” The various pianists were asked many of the same questions; one of them was “how do you memorize music?” I remember Alicia de Larrocha talking about harmonic structure and the architecture of the piece. Artur Rubinstein said “100% visual. I even memorize the coffee stains!”

As a music teacher giving private lessons (as opposed to a classroom teacher), it’s useful to know what kind of learner a student is primarily, so that you can work with them on the other aspects, because music needs all three. I’ve found usually people are strong in one, weaker in another, and very weak in the third.

Left to their own devices, auditory learners can usually hear if they play a wrong note, but since their music reading skills tend to lag behind, they need to learn the piece well by ear first. They tend to have a vague understanding of rhythmic notation and often don’t realize that they are (for example) slowing down their sextuplets to be the same speed as their 16th notes, and that they are thus slowing down the tempo: in fact they may think everything’s fine, because after all they are thinking of the notes in groups of 6.

Visual learners tend to read music well but may not hear if they play a wrong note. My favorite example of this was when a student played “Yankee Doodle” in — I think — Mixolydian mode instead of major, and had no idea why I wasn’t happy with it. (For you UK people, think of “God Save the Queen” in C major, with all B-flats.)

Kinesthetic learners tend to have a good sense of rhythm and can move the finger(s) you tell them to (never a given). They may have more or less trouble with getting music notation to trigger the correct finger movements, or hearing the quality of their sound.

If you try to teach all of your students in the same way — the “do what I do” method — you will end up with a few students (the lucky few whose brains match yours) who do very well, and a majority of students who barely progress.

Many thanks for your elucidation and how you made use of these different learning styles. It all makes sense in that context and you have made some positive changes to home in on both the stronger and weaker traits. I’ve had many an visual learner who played wrong notes, but knew it was wrong and then found difficulty in correcting it.

I was sceptical in the classroom simply because the pupils were merely audited and screened for their learning styles – following which nothing was ever done with this potentially useful insight. An example of the many educational fads which have come and gone with no real impact or usefulness.

I do find the standard of sight reading poor these days though. Pupils seem to think it’s some sort of osmosis or mystical process instead of simply knuckling down and playing through anything at all. And how many times have you experienced the ‘sight reading’ where they go back when they make an error and try to correct it?That drives me nuts! It has to be a forward moving reading exercise to hone that skill.

Its an old story, almost like language learning. It depends how the neural networks are developed or ‘trained’. This is a long researched subject of neurobiology /neuropsychology and there are many articles and some good books dealing with the brain’s processing of all these parameters while performing music. Pianists who learn early as young children have the best chances to develop exceptional artistic skills because their neural networks are still free to develop and arrange according to their needs/requirements. However, this kind of plasticity diminishes very quickly with age. Pianists who start as teenagers or adults have to struggle much more to obtain and maintain their skills for the rest of their lives.

And I can certainly testify to that; I started piano from scratch at age 35 and by 42 I had completed 7th Grade and started 8th – when I collapsed under the weight of Beethoven sonatas. In reflection, I don’t think I was very effectively taught – I never was taught the geography of the keyboard and became a very very poor sight-reader. I’d learn the notes and play the rest by ear!! Memory is important and I had a good one. But I lacked the most basic skill; sight-reading.

The way we are taught is EVERYTHING. And I take the points about the types of learners – visual, etc. I was ‘in-serviced’ about this in teaching and was very skeptical at first. Now it makes complete sense to me; some kids learn by tactile experience, others visually and lesser numbers of students can ‘synthesize’ . I’m teaching my own grandchildren using visual representations and building things themselves. It really works!