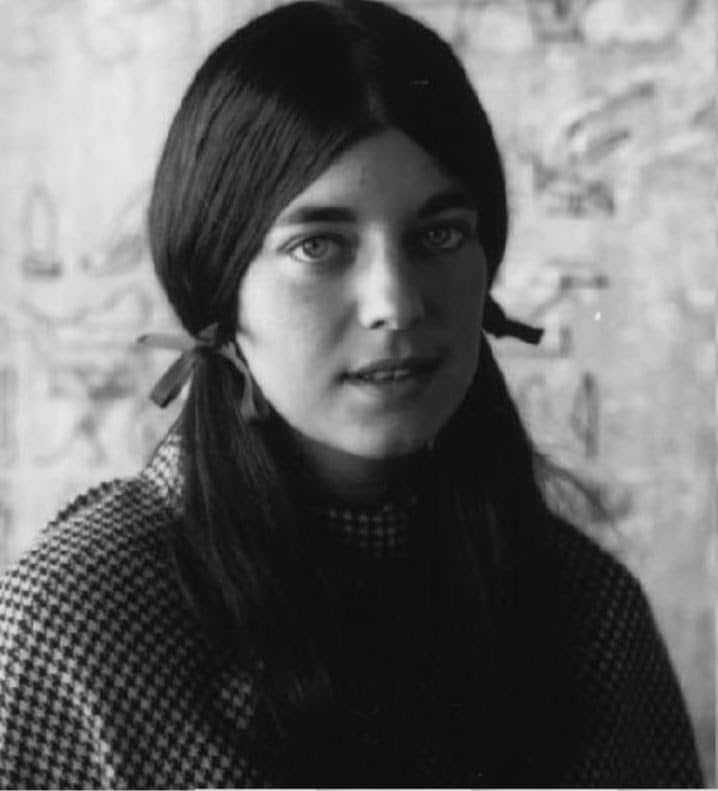

Second death on Jefferson Airplane

mainBand members are reporting the death of Signe Toly Anderson, the first female member of the rock band. She died on January 28, the same day as co-founder, Paul Kantner.

Marty Balin, another founder, messaged: ‘One sweet Lady has passed on. I imagine that she and Paul woke up in heaven and said “Hey what are you doing here? Let’s start a band” and no sooner then said Spencer was there joining in!” Heartfelt thoughts to all their family and loved ones.’

Signe, who quit the band after giving birth to a daughter in October 1966, survived cancer in the 1970s. She suffered from prolonged health problems and was 74 at her death.

Thanks for covering this. For those of us who were part of the San Francisco Scene in the late 1960s, this band was a big deal. I was a student at the small conservatory at University of the Pacific, ninety miles east of San Francisco.

Excerpt from a memoir:

During those years in Stockton, beginning in 1968, I dabbled in hippiedom—smoking dope, reading philosophy, marching in demonstrations, hanging out, and being cool. One weekend it would be coat and tie to the Opera House and the SF Symphony. The next weekend it was jeans and tie-dye to the Avalon or Fillmore ballrooms to hear Jefferson Airplane (several times,) Janis Joplin, Santana, Big Mama Thornton, Tower of Power, The Grateful Dead, Crosby, Stills and Nash, and many others. I have always regretted missing The Who and Jimi Hendrix.

I spent a lot of time sitting in those smoke-filled ballrooms trying to focus on the imagined intricacies of counterpoint, chord voicing, or anything else I could salvage from what was often, in reality, just a Wall of Sound. When I would get stoned, I could never just kick back, relax, and enjoy the music. No, I’d have to zone into it and experience the profundity of it all, even when there may have been none to experience. “Wow! Wasn’t that a bass line from Mahler 5?” Sometimes, (most of the time,) a loud band was just a loud band.

My bloodshot eyes were opened to a new concept of what the word concert could mean. In my childhood world of the Classical Piano Boy, it meant dressing up, sitting still, not talking, and, for God’s sake, not clapping in between the movements of a symphony: a.k.a. concert manners. These hoards of scruffy kids in San Francisco certainly didn’t have them.

Having missed the real Summer of Love and the flowering of the Haight-Ashbury in 1967, I was catching the rough-at-the-edges leftovers, not to say, the dregs, of the former feast. Of course, I realize that for some, it will strain credulity to even consider that throngs of unkempt, unwashed, drug using dropouts from society converging on a city and rutting in its parks could constitute a flowering of much of anything. Looking back, we may make assessments and moral judgments about what was going on, and we may even realize that the patina of time has not been particularly kind to this period with its excesses, but back then, for me, the zeitgeist was very compelling. I didn’t know exactly what it was, but I knew I wanted to be a part of it.

Fascinating and nice to see that this latest piece of news from the rock world, too, has been shared here on “Slipped Disc”. Though very much a child of the 1960s myself, I was a few years too young to appreciate the SF scene at the time, to say the very least, but I caught up with it in the 1970s, and later really began listening to the Airplane in earnest. As with a surprising number of “classic rock” groups, the classic Airplane lineup (c. 1966-70) had a very distinctive sound world and approach that was really quite their own – most especially, the vocal section of Marty Balin, Paul Kantner and Grace Slick (or, originally, Signe Anderson) singing strange, keening harmonies featuring unusual musical intervals, Jorma Kaukonen’s unpredictable, sometimes disturbing guitar lines and the exemplary rhythm section of powerful bass player Jack Casady and the precise, jazz-influenced drumming of Spencer Dryden. Their first album, “Takes Off”, still with Anderson, was essentially (highly appealing) electrified folk – one of their signature songs from this period, with lead vocals by Anderson, was their version of “High Flying Bird” – but it was the next album with Slick, “Surrealistic Pillow”, one of the “Big Three” psychedelic albums of the 1967 Summer of Love (along with “The Doors” and the Beatles’ “Seargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”) with which they really made their name. That album (also heavily drawn on by the Coen Brothers in their bizarre film set in 1967, “A Serious Man”) proved to be the group’s early commercial peak, but they then returned to the underground with their third album from late 1967, “After Bathing at Baxters”, more dominated by Kantner and featuring several longer song suites – a very early, tentative rock experiment with utilising larger musical forms. This was the most relentlessly intense, imaginative and uncompromising (and sometimes quite avant-garde) album they ever made, my own personal favourite. The still very psychedelicised “Crown of Creation” and the “political” album, “Volunteers”, followed, as did the live “Bless Its Pointed Little Head”. That was still all just the beginning of the Jefferson Airplane/Starship story, yet these remarkable early albums for the most part contain the group’s most celebrated music.

Like Glenn Hardy above, when I was younger, I too got caught up in the excitement of burgeoning 1960s/70s rock and all the limitless new possibilities it seemed to offer at the time, (at that time still) seemingly freed from the burden of heavy traditions and institutions, while I was also dutifully learning classical piano and going along to symphony concerts with my family, all of which I loved just as much.

Glenn also writes: “Looking back, we may make assessments and moral judgments about what was going on, and we may even realize that the patina of time has not been particularly kind to this period with its excesses, but back then, for me, the zeitgeist was very compelling.” That immediately put me in mind of the late U.S. film critic Roger Ebert, when he wrote (re-reviewing Michael Wadleigh’s epic 1970 “Woodstock” film a few years ago): “Somebody told me the other day that the 1960s have ‘failed.’ Failed at what? They certainly didn’t fail at being the 1960s.” For sure, there was something quite elusive, but very, very special going on back then, something which still “haunts” subsequent generations even now, I think, since, as Bob Dylan says, in a cultural sense we’re still living off the crumbs of the 1960s even today. The early Airplane, too, were an essential part of that story.

“There are three rules to rock ‘n’ roll: nobody knows what they are.” – Paul Kantner